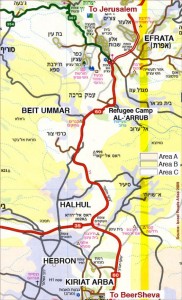

Highway 60 coils through the southern hills of Hebron and Judea, dissolves into Jerusalem, reemerges from it toward Samaria, and as it nears the biblical Mounts of Blessing and Curse, it escapes the West Bank. Roughly reflecting the ancient Route of the Patriarchs – a path which followed the imaginary line of this hilly region’s watershed – it is the longest and most traveled road in the West Bank. Joining countless nomads, pilgrims, merchants, refugees and armies that have marched upon it throughout history, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob are said to have traveled it too. Over the years, the highway’s route and appearance were altered in architectural attempts at reducing violent frictions between Jewish and Arab populations while also maintaining or even upgrading the quality of Israeli life. It now bypasses those Palestinian population centers identified as hostile, and hosts many checkpoints that regulate Palestinian movement. Monumental walls were erected, electronic fences planted, military watchtowers were raised, bridges constructed and long tunnels were carved into mountain sides in order to protect Israeli passengers from stones, molotov cocktails, explosive cars, side bombs, and sniper attacks.

Defying human actions, the scenery managed to sustain much of its rustic character. And, regardless of all the security bypasses, Highway 60 still passes through several Palestinian villages, sometimes cutting them into half, sometimes reconstituting itself as their main road, merging into a militarized discord of an increasingly urbanized rural life. With the latest Israeli easements of Palestinian movement restrictions, those residing under Palestinian jurisdiction get to use Highway 60 too. The Highway consist mostly of two lanes, contains maybe two or three traffic lights on its West Bank path, and sharply illustrates why the area is often referred to as “the wild west.” The road is a vigilante zone where lawlessness manifests itself in countless forms as national and personal anxieties find their motorized alleviation in a host of logically defying accelerations, stunts, and just plain stupid driving. I constantly witness trucks, school buses, military vehicles or simple family cars speed on the wrong side of the road without any care for basic traffic laws. Sometimes when I drive my body tenses in a disciplined manner when I notice Palestinian vehicles heading toward me. All that officially protects me is the thin white line in the middle of the road. Paint, that’s all there really is to it. But even though so many people ignore this thin white line, when the moment of truth arrives, everyone seems to possess an existential knowledge about the correct side and the proper actions they must take.

Defying human actions, the scenery managed to sustain much of its rustic character. And, regardless of all the security bypasses, Highway 60 still passes through several Palestinian villages, sometimes cutting them into half, sometimes reconstituting itself as their main road, merging into a militarized discord of an increasingly urbanized rural life. With the latest Israeli easements of Palestinian movement restrictions, those residing under Palestinian jurisdiction get to use Highway 60 too. The Highway consist mostly of two lanes, contains maybe two or three traffic lights on its West Bank path, and sharply illustrates why the area is often referred to as “the wild west.” The road is a vigilante zone where lawlessness manifests itself in countless forms as national and personal anxieties find their motorized alleviation in a host of logically defying accelerations, stunts, and just plain stupid driving. I constantly witness trucks, school buses, military vehicles or simple family cars speed on the wrong side of the road without any care for basic traffic laws. Sometimes when I drive my body tenses in a disciplined manner when I notice Palestinian vehicles heading toward me. All that officially protects me is the thin white line in the middle of the road. Paint, that’s all there really is to it. But even though so many people ignore this thin white line, when the moment of truth arrives, everyone seems to possess an existential knowledge about the correct side and the proper actions they must take.

On the eve of the latest round of peace talks, four Jews rode Highway 60 down south toward their settlement. Shortly after passing the road leading to Hebron – the City of the Patriarchs – they were ambushed and shot to death by Palestinians. Two of the victims, the parents of six, were pregnant with a seventh child. Another female victim gave birth to a single child following many years of fertility treatments. Her husband volunteers at a religious medical organization that identifies and treats the dead following “tragic incidents.” He found his dead wife inside the bullet ridden white station wagon while on duty. The 25 year old male victim left a young widow, pregnant with their first and last to be born child. All murdered for a cause, their death feeding a growing violence and suffering of people in this land.

Around noon-time the following day, the 25 Kilometer stretch of Highway 60 connecting my settlement to the victims’ home was temporarily modified. Dozens of checkpoints appeared, deserted military posts were manned and hundreds of Israeli soldiers took positions on roadsides, adjacent hills, fields, and buildings. Military traffic was drastically increased and Palestinian vehicles disappeared completely from the main road, only to be seen slowly accumulating beyond military blockades separating their local roads from the Highway. More than a thousand mourners attended a quadruple funeral service of national significance, forming a long convoy armed with enough privately owned weapons to protect itself without a need of additional assistance. Having failed to protect Israeli citizens the former evening, Israeli security forces still had to maintain order and display sovereignty through a spectacular performance of presence.

Tragedies of this kind are always expropriated from the private domain when given social meanings. ”In the building of Jerusalem and Israel we shall be consulted, and all enemies shall know they cannot defeat us,” is one example from the funeral service. But such rhetoric was mostly drowned by an excess of sorrow. A husband begging his dead wife not to leave him alone. The communal rabbi confronting God for bringing six orphans into this world. A contagious sobbing of hundreds of people. At some point I began to explore the outskirts of the funeral. Emanating from large loud speakers, the eulogies continued to follow me. At the back of the empty communal center I saw a lone middle-aged man. Black bearded, light-colored crochet Yarmulke and a short-sleeved flannel shirt. The classic look. Seated on a small school chair, an M-16 rifle laying on the ground, he silently wept.

The four dead were to be buried at three different cemeteries, and when the large service broke into smaller funeral processions, people were forced to choose one burial site over the other. I decided to follow the large procession heading north toward Jerusalem, which was also the direction of the nearest gas station. With hundreds of cars parked at the roadsides, a traffic jam was to be expected. Not waiting for the mess to coalesce, I quickly escaped the area and drove toward Hebron’s gas station where I filled my station wagon with $60 worth of gas before heading back. It was busy around the spot where the four were murdered. Policemen and soldiers tried to regulate traffic. Some funeral attendees improvised a monument out of stones, flowers, and small Israeli flags. Security forces guarded entrances to neighboring Palestinian areas, preventing Jewish troublemakers from instigating conflicts with the local Arab population. I continued driving back to see what was going on at the procession’s point of origin and found the place empty except for hitchhikers trying to catch a ride south. Returning north to the place of the attack I saw that the funeral procession already left during my 15 minutes absence. Several groups of soldiers still patrolled the nearby hills. Aside from that, a relative calmness. I parked the car.

End of Part 1 of a two-part special Fieldnote from Anthropology Now’s newest editor, Assaf Harel. Keep an eye out for Part 2 to come Monday, March 14!