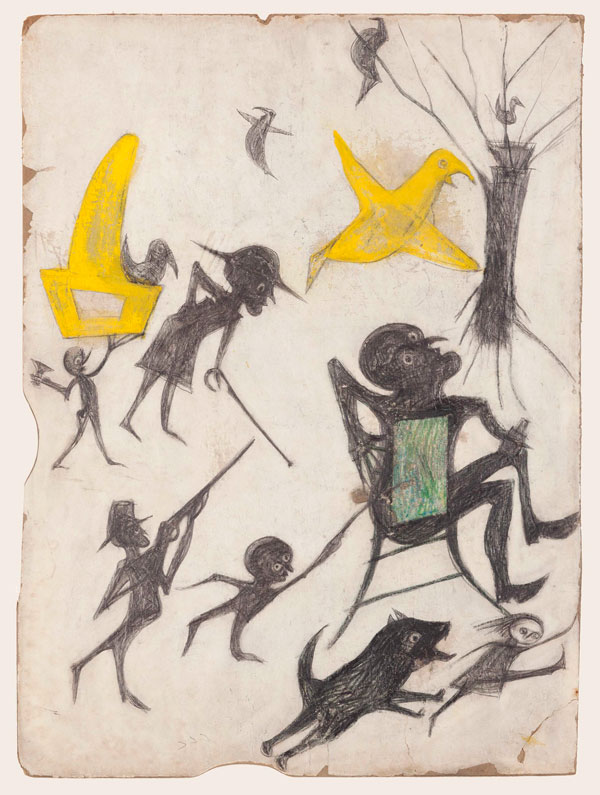

Something was definitely stirring deep within William “Bill” Traylor. In a span of four years, he expunged a lot of it, producing 1200 drawings and paintings with graphite pencil stubs and poster paint on discarded cardboard.

Traylor bears the surname of the proprietor of the plantation in Dallas County, Alabama, where he was born into slavery on April 1, 1854. Like other families, after Emancipation his remained there in the modern form of enslavement as a sharecropper. He moved to Montgomery in 1939. It was then, at the age of 85, that Traylor began to draw, producing his entire body of work by 1942.

Reading a New York Times review of the Traylor exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum made me want to see the works in person. His figures and scenes without landscapes brought Kara Walker’s paper-cut silhouettes to mind. It did not escape me that the reviewer, Roberta Smith, used a narrative of universalism to explicate the art of this “indelible individual talent,” which she characterizes as “modern and archaic… proof of Jung’s collective unconsciousness.” In the process, she did not have to dwell on a most recurring theme in Traylor’s work: America’s oldest non-secret, slavery. In that sense, I would say that Smith was “playing in the dark,” a shout out to Toni Morrison, who wrote that “all of us are bereft when criticism remain too polite or too fearful to notice a disrupting darkness before its eyes.” Indeed, Traylor has too often been presumed innocent.

The brutality of that peculiar institution was addressed head-on by Alana Shilling in her review in The Brooklyn Rail. She pointed to the tendency to overlook “the less congenial realities” in Traylor’s works or the practice of relegating them to a realm of “interpretive impossibility” denying them “semantic value.” Shilling preferred to think of his “constructions” and “exciting events” drawings, for example, as “chimeras” that is “works that offer chilling visions of an enduring slavery that can never be wholly exiled—not by wars won, not by laws of men.” While I largely agree with her, there was something offsetting about the exhibition that I could not quite articulate.

Several things struck me when I actually faced the drawings. Foremost, seeing the years 1939-1942, and the word “Untitled” on a succession of white placards next to the neat frames reinforced the fact that the images were all produced within this specific period of time. Moving slowly in the gallery, the repetition became a tempo, a sense of rhythm, which was continuously disrupted by a most visceral dissonance. Nothing. I felt nothing between the images and titles in parentheses that followed every single U-n-t-i-t-l-ed. I looked back again several times, seeking some corroboration between what I was seeing and what I was reading. Nothing.

I wasn’t imagining the disjuncture. Traylor’s works received all their titles from Charles Shannon, the young, white, formally trained artist who discovered him as he painted on the streets of Montgomery. Shannon collected the works, archived and preserved them.

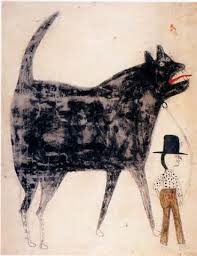

“Man and large dog,” which opens one of the two exhibitions on view at the American Folk Art Museum, is the drawing of a small white man holding the leash of a humongous black dog with bared teeth and his red tongue sticking out. The man may be steering this menacing beast, but it is unclear that he can control him. Which begs an inevitable question, what exactly happens to black rage?

I think Bill Traylor knew.

Gina Athena Ulysse is associate professor of anthropology at Wesleyan University in Middletown, CT. She is also a poet, performance artist and multi-media artist. She is the author of Downtown Ladies: Informal Commercial Importers, A Haitian Anthropologist and Self-Making in Jamaica (Chicago 2008) and the forthcoming bi-lingual collection of post-quake dispatches, essays and meditations, Why Haiti Needs New Narratives. She is in the process of developing, VooDooDoll, What if Haiti Were a Woman, a performance-installation project. Ulysse’s writing has recently appeared in the journals: Gastronomica, Souls and Transition.

Gina Athena Ulysse is associate professor of anthropology at Wesleyan University in Middletown, CT. She is also a poet, performance artist and multi-media artist. She is the author of Downtown Ladies: Informal Commercial Importers, A Haitian Anthropologist and Self-Making in Jamaica (Chicago 2008) and the forthcoming bi-lingual collection of post-quake dispatches, essays and meditations, Why Haiti Needs New Narratives. She is in the process of developing, VooDooDoll, What if Haiti Were a Woman, a performance-installation project. Ulysse’s writing has recently appeared in the journals: Gastronomica, Souls and Transition.

One Response

It is sad that so few of us get any recognition until after we are gone. Then opportunists begin to psychoanalyze our defunct minds and begin to see the value of our productivity, too late for our personal benefit. Others plunder our production and reap the benefits.