Abenójar, like many farming communities in the Spanish Province of Castilla-La Mancha, inhabits the past while also embracing the present. Its serpentine streets are lined with rows of uniform structures; the majority of homes were built or refurbished in the 1970s and 1980s. The architectural aesthetic feels recent and contemporary, not quaint and historic. Only those cottages bordering the outskirts of town, nestled in the rolling red and green landscape unique to the Tirteafuera River Valley, hint at a more distant past. Most of Abenójar’s 1,547 residents can remember a time before the streets looked so new and homogenous. An aging population dominates in a region where younger generations, caught between the lasting effects of the recent economic crisis and long-term shifts in traditional rural economies, are forced to migrate to find employment. On summer evenings, groups of women in flowery shifts gather in lawn chairs that spill over the borders of Abenójar’s tiny sidewalks, occupying significant chunks of the paved streets. Against a backdrop of matching doorways and new brick walls, they beat their chests with brightly colored fans, forcing cool air to caress the lines and ridges of their beautifully worn faces. Practices from another time coexist with all that is new and different.

I spent time in Abenójar while conducting ethnographic research in Spain during 2013 and 2014. I saw that for many of this town’s residents, especially those who witnessed the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) and its aftermath, the melding together of past and present can feel incomplete. The silence surrounding acts of violence that marked the push and pull of everyday life during Francisco Franco’s long dictatorship (1939–1975) continue to weigh heavily on those who experienced political repression first-hand. In the decades following the war, day laborers were imprisoned and tortured. Others were assassinated and disappeared — their bodies tossed into roadside ditches and unmarked graves. This physical absence marked victims’ families as unruly, deviant and undesirable; those who were left behind faced social and economic isolation that persisted across time and space. Fear became a constant backdrop against which families struggled to survive. After Franco’s death in 1975, Spain entered a democratic transition that advocated moving forward by never looking back. The memories of those who had wrestled with the effects of political violence had no place in the emergent democratic project. Consequently, their experiences with absence and violence have never been publicly or judicially recognized. Their intimate stories have never been incorporated into mainstream historical narratives. The past that Abenójar inhabits and the present it embraces are marked by these silences. Memories of an unrecognized past palpitate at the surface of village life.

***

In June 2012, the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory exhumed a mass grave located in an abandoned corner of the Abenójar Municipal Cemetery. Responding to petitions made by victims’ kin, the Association’s technical team provided the forensic expertise needed to disinter and identify the skeletal remains contained in the unmarked burial site. As in most exhumations carried out in contemporary Spain, the investigation was a collaborative event, in which victims’ kin, villagers, local researchers and forensic experts shared their knowledge about the lives of those who were missing. According to documents obtained by anthropologists in local and military archives, seven men from Abenójar and nearby villages were assassinated by the Franco regime between September 1939 and June 1941. After cross-checking villagers’ testimonies with this archival documentation, experts and victims’ kin concluded that the burial site could contain the remains of several, if not all, of the disappeared: Juan Pérez Arrellano, Avelino García Romero, Manuel Marmolejo Pérez, Isabelo Nieto Fabián, Sixto Fernández Cas- tillo, Daniel Yepes Padilla and Teófilo Soriano Anguita. After several days of excavation, the team recovered the bodies of only four men. The skeletons were carefully labeled, packaged and transported to the Association’s laboratory in Ponferrada. With four bodies and seven names, experts hoped that DNA analysis would make it possible to reconnect the recovered skeletons with their individual identities.

The exhumation in Abenójar was not a unique event. During the last 15 years, an estimated 2,000 bodies have been exhumed from nearly 400 mass graves. Absent official state recognition of these crimes, the kin of those who fell victim to 20th-century fascism have turned to forensic science as a tool for claiming public recognition of their experiences with trauma and loss. The children and grandchildren of Spain’s disappeared, together with teams of volunteer forensic experts, have purposefully imitated transnational forensic practice in order to unearth and make public biological, osteological and historical evidence that calls into question dominant historical narratives about the re- cent past [1].

However, throughout this process, the local uptake of forensic techniques and technologies has been thwarted by government-mandated austerity measures that have stripped forensic teams of public funding, by amnesty laws that prohibit defining Franco’s victims as victims of crime and by the Spanish Transition’s enduring pacto de olvido — or pact of oblivion — that has situated historical forgetting as a mode of political consensus and social modernization. As a consequence, exhumation projects are carried out at the unruly edges of legal procedure. They can result in the positive identification of victims’ remains, but the crimes that produced these disappeared bodies are still not recognized by the Spanish state [2].

***

On a Saturday morning in early May 2014, Abenójar was bustling with movement. Despite the sweltering, early-summer heat, residents gathered in small groups and made their way to the local community center, a large hall at the edge of town. Inside the building I assisted a group of anthropologists who buzzed through the space as they attached cameras to tripods, connected laptops to projectors and crosschecked handwritten notes with printed programs. Residents began to fill the building, many carrying tricolor Republican flags, a powerful symbol of the democratic government that was overthrown by the military occupation that began in July 1936. Almost two years after the exhumation at the local cemetery, representatives from the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory were once again in Abenójar, this time to return the remains to victims’ kin and the community at large. The hoped-for DNA analysis had not been accomplished. In the context of Spain’s current economic crisis and due to public funding restrictions made by the current right-wing government, the Association was unable to raise the 2,000 euros that would make such DNA tests possible. The forensic team had been unable to make direct, genetic links between victims’ names and the unearthed bones. The precariousness of historical memory work in Spain was made palpable once again.

Unable to accurately match the four skeletons with the seven identified victims, members of the Association arrived with four large plastic boxes, each labeled with a sheet of paper that included a drawing depicting three men carrying the bloodied corpses of two victims. In the picture, the men stand at the precipice of a large hole in the ground as they pause before throwing their victims into the opening in front of them. Underneath each drawing, the boxes were labeled: “Victim 1,” “Victim 2,” “Victim 3,” “Victim 4.” The phrase “Assassinated by the Franco regime” was written below each individual’s number. The plastic makeshift coffins were placed in a corner near the community center’s main entrance. Members of the Association quietly monitored the containers as 300 townspeople crowded into the main hall.

In Spain, memorial events of this kind, in which human remains are returned to victims’ kin and the communities to which they belong, are a key ingredient in exhumation projects. While the act of unearthing transforms unrecognized experiences and hushed narratives into publicly visible ones, it is the return of scientifically analyzed human remains that has become a powerful symbolic ritual, through which families claim public recognition of their loss. The devastating trauma of disappearance lies not only in the absence of one’s kin, but also in the impossibility of laying them to rest. The ritual of return reverses this predicament; it undoes the inability to properly mourn those who have died. These highly public and participatory events allow victims’ kin to give homage to the missing. In turn, these families become the protagonists of a new ritual that demands that their experiences — their histories — be recognized and validated within their communities. Although memorial rituals often resemble overdue funerary processions, they are decidedly secular and political. Before recovered remains are re-inhumed, memorial events tend to revolve around the presentation of forensic data. Forensic reports are transformed into colorful PowerPoint presentations that explain the technical details of an exhumation, including information about how the mass grave was located, what testimonies were collected and how the skeletal remains were measured and analyzed. In the absence of judicial procedures capable of officially recognizing the crimes that produced these deaths, forensic expertise transforms testimonies, archival documents and human bone into the hard evidence that visibilizes these silenced histories of forced disappearance to a local forum of observers.

In Abenójar, the memorial event began with a presentation given by members of the All the Names Project — a research initiative that seeks to identify victims of political repression in the Province of Ciudad Real and to re-narrate their life histories. Following this, the lead archaeologist of the Association for the Recuperation of Historical Memory explained the exhumation process in detail while attentively shuffling through tens of dozens of slides. He was careful to note that the case of Abenójar was unique. Historical, archival research proved there were seven victims killed in and around the village in the months and years following the war. Holding back his own tears, he explained that the remains being returned to this community were a symbolic representation of all seven victims. He expressed his commitment to securing the funding that would allow them to complete DNA testing, but in the interim, it was time for victims’ kin to mourn their loss. Waiting much longer would mean that the direct survivors of the disappeared, many of them well into their 80s, might not be able to participate. A burst of applause erupted in the community center, and members of the Association ceremoniously filed into the main hall with the plastic containers in hand. The audience stood, raising their fists defiantly into the air. Victims’ kin approached the boxes and gently retrieved them. As audience members cheered and camera flashes flickered, the families turned and began to exit the hall, initiating the long march back to the cemetery.

Bearing the heavy plastic containers, victims’ kin steadily made their way through Abenójar’s twisting streets, unsure if the particular human remains inside corresponded to their missing loved ones. Hundreds of community members followed, providing their presence — their public support — as the families made their way to the cemetery. The fact that there was no genetic proof linking the recovered remains to the kin who transported these large boxes did not seem to matter. On this day, the community would participate in a funerary march that had come late, but not too late. More than seven decades after the victims’ disappearance, their children, grandchildren, nieces and nephews would finally lay their loved ones to rest. The streets were silent as the crowd stopped in front of the Town Hall. Murmurs turned into chatter, until someone called for a minute of silence. Victims’ kin held the boxes defiantly, their backs turned to the government building. The stillness of the moment acted as a call for recognition. Together with their neighbors, the families were determined to reverse the humiliation — the heavy sense of absence — they had suffered privately and in silence. A minute passed, and a local resident who had participated in the exhumation made a loud call to resume the long walk. The crowd recommenced its slow march to the cemetery. A trumpet moaned as the group entered the burial grounds. The boxes were inserted into the mausoleum niche, and cemetery workers quickly placed and secured a marble plaque that read, “The victims of Francoist repression gave their lives in order to defend legality, liberty and social justice.” Underneath, the memorial inscription was engraved with the names of the seven disappeared men. As of this writing, the four bodies are the only remains to have been recovered.

***

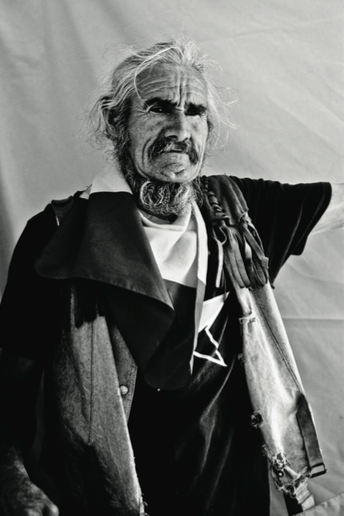

The following visual essay includes a series of portraits taken during the memorial event. Addressing the issue of recognition, my project was initiated as a way to think both ethnographically and photographically about the narrative spaces that emerge during exhumation projects. For the families of those who fell victim to political violence, the process of narrating one’s family history often has been confined to the space of the home.

During and after the dictatorship, absence and loss were experienced privately and in silence. Exhumations in contemporary Spain help undo that silence, becoming events in which these family histories can be publicly voiced. As local researchers work with victims’ kin, new forms of knowledge about the past are created. Memories, both individual and collective, are reinserted into public circulation.

During my fieldwork in Spain, I frequently collaborated with members of the All of the Names Project, who organized the event in Abenójar. While preparing for the community gathering, we discussed how the restitution of identities through the disinterment of human remains often signified a similar restitution of dignity to victims’ kin. The forensic process forcibly breaks the silence regarding individuals’ intimate, fragmented experiences with political violence. Although the Spanish state does not provide legal or official forms of recognition regarding these crimes, the public return of remains is a loud call to re-think how the past is understood and narrated both locally and nationally. In this context, many victims’ kin actively seek out opportunities to publicly voice their stories. For members of the All of the Names Project, many of whom are anthropologists who analyze, produce and write about still and moving images, encounters between photographer and subject often become sites where family histories re-emerge. The recuperation of victims’ remains often helps stimulate and produce the information and knowledge that was once absent about their missing loved ones.

During the meal following the re-inhumation at the municipal cemetery, I invited victims’ kin and community residents to a makeshift photo studio, where they were photographed and asked to discuss what they had seen and heard during the day. Emphasizing the connection between portraiture and expressions of subjectivity, I approached the photographic encounter as another point of entry for reclaiming a turbulent past. As both photographer and ethnographer, I quickly became the listener who received a wide variety of narratives that recounted people’s memories regarding the Civil War, its violent aftermath and the long period of silence that had enveloped the community. For those who were direct victims of political repression and those who witnessed that repression, the opportunity to be seen and heard generated new forms of recognition. For younger generations born after the democratic transition, portraiture sessions were a way to learn about these expanded local histories. In this process of weaving together experiences and memories, new histories emerged as a source of common knowledge about the past.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank members of the “Todos los nombres de la represión franquista de posguerra Ciudad Real” project at the National Distance University of Spain (UNED), especially Jorge Moreno Andrés, Julián López García and Alfonso Villalta Luna for their guidance, collaboration and support during the completion of this visual essay.

Notes

1. The application of scientific, forensic methods to the study of mass violence and acts of genocide first originated in Argentina in the early 1980s, when physical anthropologist Clyde Snow traveled to Argentina to train a group of doctors and anthropologists in methods of osteological analysis. These young students eventually would form the Argentine Team of Forensic Anthropology, also known as the EAAF, which now works in locations across the globe. Since the mid-1980s, scientific methods of identification have been used by a wide variety of scientific experts who work to collect evidence regarding human rights abuses and the systematic use of violence by different actors. How individual investigations are carried out often depends on the particular political, judicial and social contexts of the specific crimes being analyzed. However, experts involved in this work are part of an international community of practice that shares and compares methods, supports training initiatives and provides mutual support for groups involved in this kind of work. Christopher Joyce and Eric Stover describe the move to apply forensic methods to the study of mass human rights abuses in their book Witness from the Grave: The Stories Bones Tell.

2. Due to the costly nature of DNA analysis, positive identifications are not always made through genetic analysis. In many cases, forensic experts collaborate with local historians, townspeople and archivists to locate military documents that may include information about mass killings. This information is crosschecked with osteological analyses of human remains that allow experts to estimate the age, sex and stature of each skeleton. Personal objects recovered in mass graves are also used to identify remains. For example, in 2014 a team of forensic experts and volunteers exhumed three mass graves in the town of Monte de Estépar outside of the city of Burgos. The existence of the mass graves had been common knowledge for decades. The region of Burgos has long been known for the political repression experienced there during and after the war. The unmarked burial site in Monte de Estépar was rumored to have been a site for the “dumping” of political prisoners detained in the Provincial Prison. During the exhumation, 76 bodies were recovered and a fourth grave was located. The long-awaited exhumation project had been funded through a local crowd-funding campaign that auctioned a series of artworks regarding the burial site. In March 2015, team members returned to exhume the fourth grave containing another 20 victims. Due to the number of victims and the lack of public funding, DNA identifications were not feasible. Consequently, team members had to rely on non-genetic forms of identification. Although local police were aware of the exhumation, no judge attended the crime scene before, during or after the investigation.

The Arts of Recognition

By Lee Douglas

Suggestions for Further Reading

Ferrándiz, Francisco. 2010. “Exhuming the Defeated: Civil War Mass Graves in 21st-Century Spain,” American Ethnologist 40, no. 1 (2010): 38–54.

Joyce, Christopher and Eric Stover. Witnesses from the Grave: The Stories Bones Tell. New York: Bal- lantine Books, 1991.

Lee Douglas is a doctoral candidate in Sociocultural Anthropology and a member of the Graduate Program in Culture and Media at New York University. She also holds an MSc in Visual Anthropology from Oxford University. Her research focuses on the intersection of forensic science, modes of documentation and image-making practices related to the excavation of mass graves and the identification of remains in post-Franco Spain. Paying close attention to the historical, social and political uses use of forensic evidence, she considers what the entanglement of science, documentary practice and visual representation reveals about the production and mobilization of knowledge in times of economic austerity and political change.

Originally trained as a photographer, Douglas is committed to re-thinking visual storytelling as a mode of collaboration that can visibilize experiences with political violence. She is a contributor to the publication and exhibition Human Rights/Copy Rights: Visual Archives in the Age of Declassification (University of Chile, Museum of Contemporary Art), a co-curator of Artless Photographs, a multi-media exhibit showcased in the 2012 FotoFocus Photography Biennial in Cincinnati, a co-producer of the e-book Chile from Within published by photographer Susan Meiselas and co-director and producer of the short documentary What Remains. She is a founding member of the Madrid-based visual anthropology col- lective MateriaPrimaLAB and the visual research initiative SplitScreen.

Óscar Rodríguez Alonso is a sociologist and self-taught photographer. Since his retirement, he has served as a volunteer for the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory in Ponferrada, Spain and the Aranzadi Forensic Team in the Basque Country. Working primarily with photography and video, Óscar assists forensic teams with the documentation of exhumation projects. In addition to his work with these groups, Óscar is an avid environmental photographer who takes a special interest in photographing Spain’s many Roman archaeological sites.