Mary D’Ambrosio

To cite this article: Mary D’Ambrosio (2019) On the Road During a Time of War: Migrant Journeys Through a Wary Europe, Anthropology Now, 11:3, 1-11, DOI: 10.1080/19428200.2019.1733824

Conversations with dozens of Middle Eastern and African migrants crossing Europe suggest that refugees often pass through three stages of migration: trepidation before the dangerous journey, jubilation after arriving in apparent safe zones and then sometimes disillusionment.

Trepidation: Sinking or Swimming in Izmir, Turkey

Seven members of the Hawash family sat stiffly in a café in the main square of an Izmir district nowadays known as Little Syria. Palestinians from Aleppo, they were meticulously groomed, as if ready to board an important flight. Mother, father, sons, daughters and spouses had been camped out there for four days. The women were sleeping in one of the $8 a night hotels, while the men bedded down, along with many other men, in a nearby park.

“Our home was bombed, so we left for Turkey,” said Hanije Hawash, 23 years old and a mechanical engineer. “We spent two years in Istanbul, where my brother Mahmoud had a job repairing mobile phones. We all lived on his job. But Istanbul is such an expensive city. We could not survive there.”

Hanije’s mother, a doctor, worked her worry beads; the children fidgeted in their seats.

This district, which before the refugees arrived was named after its central feature — the Basmane train station — has always been a point of departure. Only now people are leaving by sea. Though nominally a center of “illegal” activity, this is a clandestine neighborhood only in name: a long queue of yellow taxis waited openly on a main avenue, to take migrants to their departure points in the hidden coves of the Aegean coast. Smuggling activities are conducted in broad daylight — and in shouting distance from a police station planted smack in the center of the action. The neighborhood is tense with furtive transaction and planning. It’s the most dangerous step: the choice of smuggler, of boat, will make the difference between life and death. The Hawashes have paid $1,000 per person to be smuggled across the sea to Greece. Now they’re waiting for the signal to depart.

“We’re now trying to go to Germany, or to Sweden,” said Hanije Hawash. “Because in Aleppo, everything is over. My fiancé is in Nor- way; perhaps this is a place we could also reach.”

“We don’t have another choice,” she continued. “At last we decided: we will travel in a boat.”

“Syria is very beautiful,” said Mahmoud. “We wish we could go back there. But we have no house there.”

We spoke on a Friday afternoon in July 2015. Evidently they left that night, as I never saw them again.

Last night Raghad Alhallak and her family had been ready, with their daypacks and life preservers, to be picked up for the journey across the Aegean. Then their smuggler sent a message: the sea was too rough. So Raghad, a slim, forthright young woman in a pink and purple headscarf decorated with hearts, waited with her mother and siblings on the sidewalk on Hotel Street. Her younger brother and a new friend pranced around her. They hoped to try again that night.

We exchanged Facebook and email addresses. When I looked her up the next day, she was already following me. Her page was mostly filled with joke videos and “wassup”-style comments to friends, but one had a picture of a downcast figure, standing at the bottom of a steep hill and carrying a heart.

“Long distance ahead,” she’d written, adding a frowny-faced emoticon shed- ding tears. It had 55 likes. “God bless you and your heart, habibi,” a Facebook friend wrote. It was a journey of about 1,850 miles: a distance Raghad had never traversed, or even imagined traveling. The next day she messaged me that again the sea had been too rough and their departure again delayed.

“Our plan was to live and work in Turkey,” Raghad explained. “We spent two months in Ankara. But we couldn’t survive there. It’s hard to find a job, and even if you do, they try to cheat you. They lower your pay, because they realize you have no choice. You have to take whatever they give you.

“Here in Turkey, some people love us, and help us; some people hate us. When we first arrived, some Turks we met were afraid we were terrorists; they thought we had a bomb.”

Her father and older brother crossed the sea here two months earlier.

“They crossed the sea by boat. They made it, thank God. Now my father is in Germany, in Bonn, and he gets 600 euro per month [300 euro each for himself and his son], and a house. He is learning the language.”

For the journey they were about to make, they’d paid $2,000 each. The parents, Hanan and Kasem, sold their business, their home and their jewelry. They divided the cash, wrapped it in nylon satchels and hid them beneath their clothes. Then, together, the family crossed the border into Turkey.

“We’re going on a small boat, with only 40 people. No, no captain. They will push us toward the shore. But Greece is very close; it’s right there.” Raghad gestured vaguely ahead. “It will just take an hour or two; then we will be there.”

Their goal was the Greek island of Kos. Just five miles from the closest point on the Bodrum peninsula, it was the latest favored crossing point. It was the crossing where, two months later, the toddler Aylan Kurdi would drown.

“If we live, we live,” Raghad said resignedly. “If we die, we die.”

There was trepidation, and also weary resignation. It was the end of the line. People were treating the sea as the last barrier. But it also carried waves of hope. If the Alhallaks and others like them made it — and the odds are that they would — then all the Western world would be open to them.

“After we land, we plan to walk,” Raghad told me resolutely. “We will keep walking until we reach Germany.”

After this conversation, I didn’t hear from her again. She posted no more pictures on her Facebook page, and her app indicated that she hadn’t signed on.

Jubilation: Celebrating Survival in Siracusa, Sicily

What the migrant crisis coverage often fails to capture is the joy.

“I kissed the ground! We’re celebrating! We made it,” said Mohamed Ahamed Ibraham, the day after arriving on a wooden boat from Libya.

We were in a public park in Siracusa, Sicily, and Mohamed, a 22-year-old mining engineer from Sudan, could barely believe he was here. He has a master’s degree, he said, and experience working for a Chinese mining company. But after he lost his job, he considered his prospects bleak. Freshly showered, and dressed in new clothes given to him by volunteers at a nearby church, he made careful notes in a thick leather-bound agenda: a penciled map, phone numbers of European contacts. A list of tomorrow’s out- bound trains. Outside of this park, where he and other migrants were temporarily sleeping, was the lethargic Sicilian city.

I experienced three Siracusas: there’s the tourist city, of the famous ruined amphitheater, and the historic seaside neighborhood of Ortigia, of small artisanal restaurants and pretty hotels — the only one the guide- books mention, and where the big cruise ships briefly call. There’s migrant Siracusa: most recently of dark-faced people arriving on coast guard ships or, miraculously, under their own power, who either hang tentatively around at the edges of markets and crowds, as if unsure of what to do next, or who look to the left, then to the right, and are quickly gone. And then there’s the angst-ridden local city: of crisis, of closed shops and underemployment, of lethargy, resentment and muted desperation; of groups of able-bodied local men and boys sitting hunched together on benches, or leaning heavily against the stolid trees; of trains that might or might not come. It felt to me like rural Mexico circa 1985 — a big, hopelessly empty landscape, and a sense that the most ambitious people have fled. The torpor and fatalism of the place are an impossibly wrong fit for the energetic immigrants, who have risked their lives for the uncertain chance to do, act and create! Mohamed picked up on this right away.

“Nobody is staying here; everyone I am talking to has plans,” he told me. It was his second day in Italy. “I hope to go to England, to study. I want to get my Ph.D. That is my dream.”

Mohamed comes from the minority Berti tribe, lately experiencing persecution from local Arab militias.

“You understand: we are an African tribe, and that means there is nothing for us there. Everything is controlled by the Arab tribes, and they give only to their people.”

To get anywhere in life, he felt, he had to leave.

“I paid more than $3,000 to cross the sea. First, I went to Cairo. After one week, I went to Libya, and came together with seven friends. There were 220 people on our boat. We had no captain. Our contact put us on this ship, and said we should aim for that line on the [Italian] coast. He said we should call the Red Cross after four hours. Well, we did call after four hours, but they said we were far away from international waters, 109 miles away [international waters generally begin 230 miles away from any coast].

“And then we got lost at sea. We all took turns driving. We were out there for 11 days.

“You know, I was not sorry. I said to myself, ‘Maybe we’ll arrive, or maybe not. Either we die in Darfur, or we die in the sea.’ “Finally we met the Swedish Coast Guard, in international waters. They carried us to Italy, and it took us 28 hours to arrive here.”

He downplayed one of the most contentious issues between Europeans and the new arrivals: the fear of Muslim influence on a Christian-dominated continent.

“I was born Muslim, but in fact I am not Muslim, or Christian,” he said. “I really believe in better relations between people, and I think it’s not useful to say ‘Muslim’ and ‘Christian.’

“Like here” — he gestured toward the Church of St. Thomas next to the Pantheon, that is hosting him — “no one asks you why you are here. They don’t ask who you are. They say, ‘Come eat!’”

And in fact, at noon a messenger on a bike came to the park to call the men to lunch. After he arrived in Italy, Mohamed called home. He is the second oldest child of 10: they are five sisters and five brothers, a family of farmers.

“My father said to me: ‘Keep going, my son.’” He opened his appointment book. “Now I will go to Rome, and from there, let’s see. I hope to go to England, to study. That is my dream. When will I go back [to Sudan]? When the government changes, then I will go back.” I returned to the park the next day, hoping to continue our interview. But he had already gone.

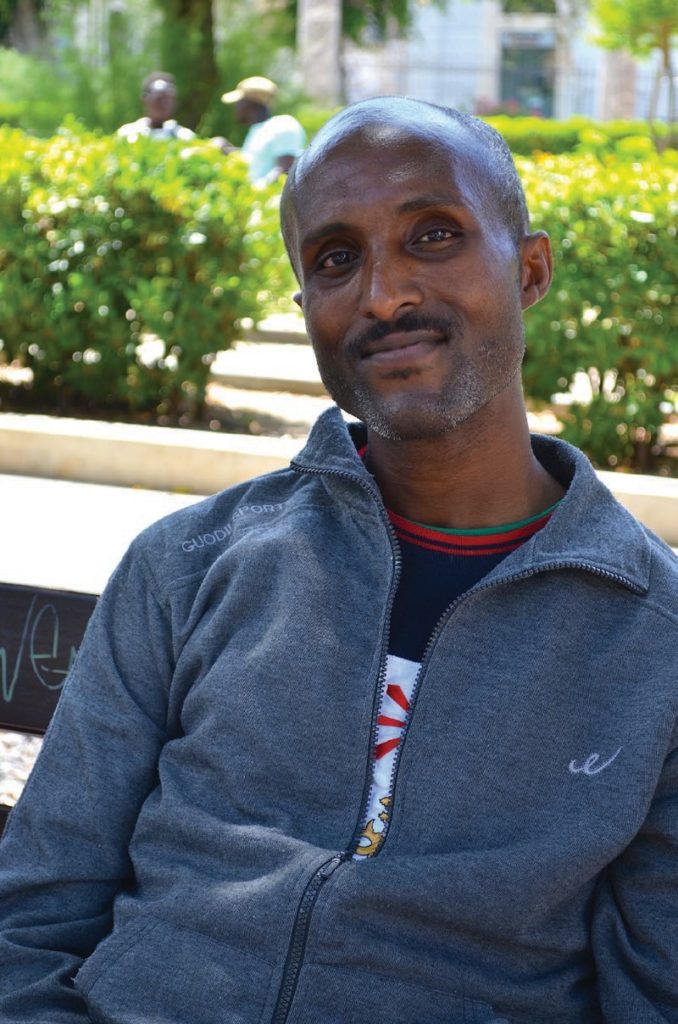

“This kind of trip is dangerous, but it is absolutely necessary, for people who want to make something of their life,” said Mewael, a 36-year-old Eritrean and former English teacher, who arrived yesterday and is staying in the same Siracusa park as Mohamad Ibraham. He, too, was methodically making plans. He excused himself frequently to make, and take, calls on his battered flip phone.

“I am out of money now, and waiting for my sister to send some money from Saudi Arabia,” he explained. “Then I will continue to my other sister in Holland.” Mewael had to deal with a problem most migrants don’t: to reach Italy, he first had to escape from his own country.

“I was an English teacher in the military, teaching children in grades six through nine. The official term was supposed to be two years. But after you finish your service, they don’t let you leave. ‘We struggled for 30 years for the freedom of the country,’ they tell you. I ended up staying there for 10 years.”

Mewael — a pseudonym — spoke deliberately and carefully about the steps he took to arrive in Siracusa.

“Three years ago, my family arranged a marriage for me. They presented me with a girl, and I accepted. Because of my military assignment, I had no time to meet a wife, and after we were married, I also had no time to see her.” He understood that Eritrea was unlikely to offer him, or his family, much of a life. “After I was married, everything grew clear. I realized: I am married now, and I have to make my life.

“In Eritrea, there’s work, but no development,” he said. “I was earning 500 or 600 nakfa [about $33 to $40] a month. That’s meaningless money. A house, for example, costs $300,000 or $400,000! I had to do something to help my family. The only way was to escape to another country.

“First, I went to Sudan. It was too dangerous to bring my wife, so I went alone. I was three years traveling. And I have not been in contact with my family for all of that time. I did not call my father or mother; I did not speak with my wife. After working in Sudan for those years, I went to Libya, and found a boat. This whole experience, including traveling, including the ship [to cross the Mediterranean], cost $3,700.

“Thank God, nothing happened to me. In Libya, they are using girls for sex, and they are hitting the boys. In the houses where they put you to wait for the boats, they kick you if you talk. They treat you like an animal. In the house where I stayed, we were three or four weeks waiting for the person who would take us to the ship. I had no choice by then. The people load you in any possible way. We had a medium- sized boat, and there were 400 of us in it. I was thinking that the boat was too dangerous.

“After 10 hours, someone called an inter- national number. I’m not sure who came for us. But we were picked up by a ship, where I began to hear some English. We were taken to a center in Pozzallo [the Italian government reception center in Pozzallo, Sicily]. I decided not to make an asylum claim, and after five or six days, I left. It is a temporary center, and they don’t force you to stay.” He heard through the grapevine that prospects in Sicily were poor. So he set his sights on joining his sister in Holland. “I would like to study, and to work in computer science,” he told me. “I think that’s something I could do well.”

A half-dozen other Eritrean men and women travelers had attached themselves to him during the journey.

“I have become the leader for these others,” he said, gesturing toward the group, who watched us from a respectful distance. “They don’t speak any languages, but now they say they are going to Holland, too. I hope they will be all right.”

I was hauling my big suitcase along the air- port terminal curb in New York when I heard my phone ping.

It was Raghad.

“Helllloooo!!” she wrote. She and her family had reach Serbia, after just barely surviving the Mediterranean crossing. One of their 40-member traveling party had lifted a stick, popping their rubber dinghy, in a mad bid to attract the attention of a distant coast guard ship. They all then screamed toward the would-be rescuers as the boat slowly sank:

“Help, help!” “We’re drowning!”

“We have children on board.” In an hour, they were in Greece.

“Congratulations, Raghad, that’s great news!” I wrote back, balancing my phone on my bags on the curb.

“No, not yet,” she answered. “We have a lot of risk ahead of us. So please pray for me.”

Later I would learn that she was texting me from a dense, threatening forest and that the terrors before her equaled her risk of dying at sea. I suddenly keenly felt my own advantage. I’d not even considered, let alone thanked the universe for, the ease of my own journey: the coddled flight, the swift taxi home to a place I owned, in a peaceful neighborhood where I had the unquestioned right to stay.

Disillusion: Stuck in Italy

If journalists focus on the hair-raising sea crossings, and the thirsty treks across hos- tile terrain, migrants focus most on the “after.” What next, they ask themselves, and one another, incessantly as they brave dark waters and sneak across hostile borders. Where will I make my life, and how? Those questions dwarf the temporary threats and inconveniences of their terrifying journeys. Since it can be very hard to leave a country after “registering” or receiving asylum there, the choices made now can end up governing the rest of their lives.

Negus applied for working papers shortly after landing in Sicily, and was thrilled when they came through. But his joy faded after he failed to find steady or sustaining work.

“Here in Italy, when you are an immigrant, they take advantage of you,” the 32-year-old Eritrean said bitterly. He had been living for seven restless years in Ragusa, Sicily, where he works intermittently as a translator and guide for nongovernmental organizations, helping arriving migrants. He made what he now regards as the tactical error of applying for asylum in Italy. Under EU rules that restrict migrants to the country where they apply for asylum, he was now stuck there. He’s spent hours second-guessing himself and concocting new plans. Should he have stayed in Eritrea, where he was studying to be a pharmacist? Could he find a way to Canada, where two of his brothers seem to be prospering? Or can he reach his wife in Norway, where she has petitioned for asylum and where his son was born, although that country has already rejected his asylum petition?

“I wanted to go to London, and to study there. That’s where I was headed,” he explained. “You know, when you are young, you have big dreams. You want to go out, and go after them.”

He met his wife, a fellow student, while they were at university, and they married in Sudan. But his effort to bring her to Italy to join him backfired: when she arrived in 2012, he had no work at all.

“She became upset, and she decided to go back,” Negus recalled. “Then she went to Norway by herself.”

Now Negus lives rent-free with Gianfranco, a worldly divorced artist and ceramicist in his 60s, in a cave on the edge of a hill. The view is lovely, and Gianfranco has lent him an old truck to drive. The caves are filled with Gianfranco’s fantastic ceramic sculptures: scenes of Ragusa, principally, but also of Istanbul, where he has close friends. The artist’s two sons are themselves labor migrants in Scotland, where one works as an architect. This is a life Gianfranco has chosen but one Negus has been obliged to live. It was charity, and too little for his intellect and aspirations. And so he’s restless, frustrated and angry. As we drove toward a refugee center, he jammed his foot hard on the accelerator.

“I worked picking vegetables; zucchini, tomatoes and melons. It was very hot inside those greenhouses — very, very hot! No Ital- ian would put up with that!” he said. “And they don’t. I never met any Italian while I was working in the fields. Everyone was an immi- grant. There were many Romanians, and Poles. They were paid about 30 euros a day, even though the correct wage was 60 euros. But then the North Africans came — Moroc- cans and Tunisians — and they worked for 25 euros. So the money dropped.”

Next he worked in construction. But a boss cheated him out of a large bonus due when the job ended, and a lawyer at his labor union warned him that, if the union intervened, he could be shut out of work.

“The lawyer there said to me, ‘If we do something about this, he can fire you, and then you’ll have no job.’ So, what is this union good for? Here, the boss is like a god. He decides whether you will eat, or starve.”

Negus is wise to the immigration “system,” in which Italians collect payments from the Italian government, to service, process and house migrants.

“They make money on you,” he said bitterly. “They pay the boss of a center a certain amount per immigrant each day, so they don’t want you to leave. The Italians are part of the trafficking system, too.” He has reap- plied to join his wife and son in Norway. “Two of my brothers are in Canada. One was studying to be a doctor, but after five years he gave that up, to work in a 7-Eleven. Now he has bought his own 7-Eleven, for about $700,000. He has bought his own house.

“Some of my friends have done the same. And look at me: I’m stuck here; I have nothing.

“Maybe I should have stayed in Eritrea,” he mused. “Maybe I would have become a pharmacist.”

We drove past block after block of closed stores: dry cleaners, stationery shops, kitch- enware, clothing emporia and hairdressers, with their gray steel shutters pulled down to the ground, on a Monday at 10 or 11. Was it a holiday, I wondered?

“No, there’s no business,” I was often told— too little to bother opening the door.

Only the churches seemed to have any wealth, and in some places it looked, grotesquely, as if they’d amassed it all.

Adam, a handsome and robust Ghanaian of 29, rode up on a heavy old BMW motorcycle. “I tell you, I am disappointed,” he said, ragefully. “This was not what I expected, and not what I was hoping for. I also went to Germany, which is a very nice country. I went there to find a job — to make it. But Hamburg was full of other people looking for work. And with the kind of documents I have, I cannot work outside of Italy.”

We were in the courtyard of the Church of the Borgo Miniti in Siracusa, Sicily. The church was overseen by a priest who offered migrants a hangout space and meals. Adam arrived seven years ago, by boat.

“The truth is, in Europe, you cannot work anywhere,” he continued. “Immigration gives an illusion. I left my country for a reason. But here I have no good place to sleep, and no work. Even the Sicilians cannot find work.”

He was the first migrant I met who had married a native Sicilian. He and his wife, Donatella, have a 6-year-old son. But having a family to support only seems to have increased his anguish.

“I have no future,” he said bitterly. “I am 29 years old, and I need my future. I want to go somewhere good: to America, to Canada, to the U.K. or Australia.”

In Ghana, he said, he was a fashion designer and tailor, and in Italy he has applied to many design and tailoring companies. Like Negus, he’s given up on Italy. If the Italian government would give him a sum of money, he said, he’d also be happy to return home.

“But I can’t go back empty-handed,” he said. “I need pocket money: 5,000, 6,000 or 10,000 euros [$5,600, $6,700 or $11,200] to do something with. I would buy many designing machines. I would open a business. Or I could buy a taxi fleet: I’d buy two or three cars, and run a taxi service.”

His poor family back in Ghana is not beg- ging him to come home. Rather, his brother, six sisters and father are hoping for his help. He’s reluctant to go home without bringing it.

“Years ago, I thought, ‘God is great.’ God opened a miracle to me, to allow me to come to Europe. But what I have here is just a little work, a day here, a day there. And seasonal work. That’s no work for a future.” With a wife and son, his burdens only feel heavier.

“When my boy grows up, what should I tell him?” he demanded rhetorically. “What should I tell him when he asks me, ‘Papa, what did you do for me when I was young?’ I will tell him I did nothing, because I could do nothing.”

As much as I felt for Adam, I was even more struck by the attitude of his wife, whom I met later. Long-haired and retiring, Donatella lounged on the back of her husband’s bike and listened to him with the attitude of someone who had heard this speech often.

“But that’s how it is,” she said. “What can we do?” She shrugged and put her arms around her husband’s waist as they prepared to drive off.

Arriving to pick me up, my taxi driver and his wife took in this exchange. Oh yes, they complain, said my taxi driver’s wife, watching them go. But where did he get that nice bike? And his friend, with that little machine — she pointed to Adam’s friend Isaac Twum, who was listening to reggae on his iPad through earphones — did the priest buy that for him? The government has no business giving money to these newcomers, she said angrily, when the Sicilians themselves have so little. It’s that horrible phenomenon, of the poor squabbling over the thinnest of spoils — both sides feeling so needy and bereft that they cannot help one another. The Sicilians were often socially sympathetic but tended to pronounce themselves helpless to do anything for their unbidden guests. Where an American would say that we had to do something, and call for public policy change, a Sicilian might only offer sympathy, a jacket or a bite to eat. The Sicilian hasn’t been able to change policy for himself, not for centuries; it would not even occur to him to call for change on behalf of an even more bereft people.

The fatalistic southern style was the thing that most rubbed me the wrong way. It made me think of the heritage of the latifundia, which assigned everyone an immutable place in the social hierarchy, crushing aspirations and imaginations.

Having nothing, the Sicilians often could conjure nothing. I was struck by the images in a school art show about the migrants in nearby Pozzallo, where a child’s poem wished the struggling refugees a “long light to light their way” but did not think to offer help. As fellow supplicants, the Sicilians don’t expect anyone to ask them to provide. With the big manors gone, there’s no one left, it turns out, to exercise noblesse oblige.

I can do a little something: I can pluck you from the waves, and give you a blanket and a meal. But I cannot fulfill any of those giant hopes you carry with you, those giant hopes that made you risk your life on the sea: I can- not give you a Ph.D., or a livelihood to sup- port your wife, or prepare a future for your son. Only the bosses can do that, only a serious government will do that.

![]() German Nirvana

German Nirvana

Raghad Alhallak’s experience was very different.

Three weeks after her nervous text from the Serbian forest, I saw an ebullient post on her Facebook page.

“After a month of misfortune and dis- placement, of drowning, of forests and dogs, of insects, of cold and nipping, of sleeping on rocks under the moonlight … of escaping from police and fear of the fingerprint … my family and I arrived safely in Germany. A thousand praises, and thanks be to God.”

She, her mother, and her younger brother and sister barely survived their terrifying 21-day journey across six countries. But by the time we met again in Bonn, nearly a year later, the whole family had been granted asylum. They’d been resettled in a pleasant three-bedroom apartment in a leafy suburb— lovely, they allowed, if smaller than their home in Damascus. The German government would support them there for three years, with a 300-euro-per-month stipend for each per- son, while the Alhallaks study German and pursue schooling, job training and language instruction. After this, they’ll be responsible for their own support. Raghad’s father, Kasem, hopes to again work as a mechanic and auto body restorer, as he did for 12 years in Dubai. Raghad, a former law student, is hoping to switch to medical studies.

“I like it,” she said, about her life in Ger- many, in the same firm and resolute voice she spoken in the year before, when she and her family were preparing to cross the sea.

It is not as though they’ve entirely adjusted. Scarred by the journey, Raghad is afraid to enter the lush woods near the apartment complex. Nor does she date. In fact, on her Facebook page she’s listed “Berlin” as her city of residence to throw off a particularly persistent local suitor. It was the summer of 2016, and the family was transfixed with the horrific bombing of Aleppo. They spent hours watching the carnage online.

“I see children crying for their parents,” Raghad said.

It was again Ramadan, the annual Muslim religious observance marked by 30 days of daylight fasting — an especially difficult obligation in German summer, when it doesn’t get dark until 10. But Raghad loves this sea- son, and says she doesn’t mind the long hungry day. What she does mind is missing the end-of-Ramadan festivities she enjoyed in Syria: the shopping and late-night partying of Eid, which also fell during my visit. Instead of celebrating, Raghad’s parents sat awkwardly on their new couch, as if unsure of how to observe the holiday in this unfamiliar place.

“Are we celebrating Eid?” Raghad asked her mother.

Hanan shrugged.

Raghad instead scanned Facebook and followed the revelries of relatives and friends back home.

“This is what I miss most,” she said. “Friends, family and celebrations.”

For all the Alhallaks gained, Raghad’s words also betray what was lost: the warmth of a community, and the traditions all migrants end up leaving behind in the old country, or altering in the new one, no matter the circumstances of their arrival. In that way, she’s no different than any of us who have left one home for another.

Mary D’Ambrosio is an assistant professor of professional journalism practice at Rutgers University, and a journalist who specializes in writing about international issues. A former reporter for the Associated Press, and special projects editor for Global Finance magazine, she has reported extensively from Europe and Latin America. Professor D’Ambrosio’s work has appeared in the Huffing- ton Post, Institutional Investor, Islands and Working Woman magazines and in the San Francisco Chronicle, Newsday and the Miami Herald. This is the third in a series of articles meant to humanize the migration experience. Professor D’Ambrosio is also at work on a book about a family who helped bring down communism in Albania.