It speaks constantly. In five languages. “Attention, attention. I’m warning you that you’re at the Hungarian border, at the border crossing, which is the property of the Hungarian government. If you damage the fence, cross illegally or attempt to cross, it’s counted as a crime in Hungary. I’m warning you to hold back from committing this crime. You can submit your asylum application in the transit zone. Tavajoh Tavajoh. Baraye shoma hoshdar dade mishavad ke dar marze Majarestan nazdike simhaye khardar hastid …” And so on. The fence keeps on speaking, in the first person singular, menacing to whoever cares to listen in English and Farsi followed by Arabic, Urdu and Serbian, a disembodied voice emanating from speakers strategically placed every few meters along the length of the fence [1]. Conveniently, then, the fence itself becomes the most eloquent speaker on its own supposed function as well as on relevant details of Hungarian asylum legislation.

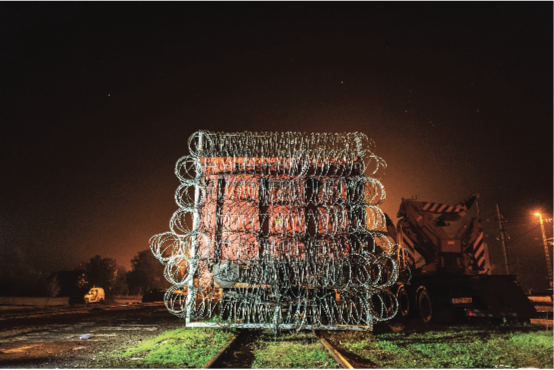

Upon its sudden appearance, a rare species of mole-rats living underneath the planned path of the fence in the flat grassy fields that epitomize the Hungarian landscape was forced into exile and possible extinction when the metal poles of the fence got drilled into the dark tunnels of their homes. The scenery of the entire Southern border, which Hungary shares with Serbia and Croatia, changed radically with the construction of the fence. Along came the militarized border agency complexes, detention camps made of shipping containers (called “transit zones”) for asylum seekers, thousands of border guards specifically recruited for the purpose and, finally, the graphic videos and photos through which the Hungarian government diligently informed its citizens on the progress of the border fortifications. Unlike what the mole-rats might believe, the fence did not just spring into existence from the ground up, but evolved into its current shape over time. Rapidly planned by the government as a response to the increased number of asylum seekers, the fence at first consisted mainly of triple-helix razor wire, with the fence proper only planted at strategic points.

By now, the Hungarian fence consists mostly of a double structure, the components of which vary somewhat as the border advances from the slightly undulating segments on the border with Croatia to the flatter fields marking the border with Serbia. Looking from that side, from the fields near Kelebija in Serbia, a migrant gazing at the external border of the European Union (EU) first notices a loose, spiral stretch of razor wire. In the beginning, most of the fence consisted of this razor helix infrastructure, like a barbed slinky extended across the landscape. Many a piece of a jacket, backpack and hoodie has ended up stuck to its spikes, torn off as people attempting to claim asylum climbed over, crawled under or slid through to meet border guards, police or unofficial militias on the other side. Those days, however, are long gone. From the spring of 2017, the coil fence has been backed up by a second front line, a tall metal fence, equipped with that now-familiar soundtrack, surrounded by sandy roads, like moats, and lookout posts, like medieval turrets.

The evolution of the fence (or the “southern protective border barrier” as it is officially known) has taken place along a path of increasing technomilitary sophistication — from a simple barbed wire to totally militarized border zone. Originally, the Hungarian press dubbed the brutal final touch to the first fence as the “Mad Max train”: a red, rusty locomotive that sealed off the final split in the fence in September 2015 in front of thousands of asylum seekers desperate to enter the European Union. By 2017, Mad Max had been upgraded with border guard complexes and watchtowers with thermal imaging cameras, the detailed operations of which the police painstakingly share on YouTube and their official website.

A central piece of the militarized border zone, the fence emerges as the key prop in the marketing of the “Hungarian solution to migration” [2]. The first two elements of the solution — pushing migrants further out by selective legal and physical closure of certain borders and by mechanisms of deterrence such as detention — are not original inventions of the Hungarian government. Rather, the peculiarity of the Hungarian solution to migration lies in its visual effects, brought to citizens via the colossal and continuous propaganda campaigns, centered on the fence. The extensive use of media and the aestheticization of the fence as a backdrop are part of the state politics of the border.

The Hungarian government and border police go to great pains to inform critical voices that forces from FRONTEX, the European Union external border agency, are also always present there with them. The message is clear: no irregularities or violence toward asylum seekers can take place; we are all safe. On that side, there is the wild Balkans and those migrants who are marching toward us. On this side, there is us: whiteness, conservative values, Christianity and, importantly, most of the European Union, including the decision-making bodies that have drafted the very legislation that the fence is said to embody. The European Commission, the Parliament, the Council — all are safely inside, in places like Brussels and Strasbourg.

The international press often overlooks the presence of FRONTEX at the border, disparaging the “Hungarian” fence as yet another manifestation of postsocialist countries’ inability to modernize and catch up with “European” values of liberty and equality [3]. To reduce the fence to a whim of the nationalist-conservative Fidesz government of Hungary, however, somewhat distorts the big picture by bypassing the emergence over the past decade or more of similar border fences on different borders of Europe. The fence is a manifestation of the complex components of EU asylum law that pushes border management away from the center of the Union; the Dublin regulation, asylum directives, safe third country rules and bilateral readmission agreements all ramify onward to Serbia, Macedonia and Turkey, pushing out EU border management further south and east [4].

Instead of an attack on European values, and a marker of Hungary’s insufficient modernization, then, the fence should be seen as a logical continuation of EU border policy, not an aberration of it [5]. Like other fences, it stands as a materialization of the wider “borderscape” of the EU, stretching from these outer boundaries to internal ones located in offices, refugee camps, and the urban spaces of Budapest, Berlin and Stockholm [6]. The fence is a physical reminder that liberal capitalism as advanced by the EU relies on an artificial binary between the economic and the political, and that the figure of the migrant, crossing the border of that binary under false (economic) pretenses, has been constructed as the encroaching Other, the intruder into EU space [7].

Simultaneously marking the center and the periphery, the fence further blurs ideas about the location of Europe and its actual landscape. Looking from Western Europe, Hungary is an outlier at the margins of the EU; but from the viewpoint of a migrant seeking asylum in the EU, Hungary may emerge as a central site. EU asylum law requires migrants to stay in the member state they first entered and ensures this by collecting fingerprints in a common database. A migrant who continues onward from Hungary may, then, face a so-called “Dublin deportation” back to Hungary, or to other external border member states such as Bulgaria or Greece.

The configuration of people at the fence is a powerful reminder of its evolution from a simple coil wire into a totalizing, military zone. The initial builders of the fence — including prisoners, soldiers, and public workers hired through workfare schemes — have given way to watch towers and newly recruited specialized police, known as “border hunters” (határvadászok), mostly young people from impoverished rural areas promised a stable income and a career. When the fence was originally set up during the long summer of migration in 2015, there were thousands of people crossing the border every day. Some years later, migrants in the immediate vicinity of the fence are mostly detained inside the container facility within the so-called “transit zone.” As only about 10 people are allowed in per day, thousands remain stranded in Serbia, forming what Martina Tazzioli has conceptualized as temporary, divisible multiplicity on the border zone: groups of people sharing in common only the fact that they are trapped in the border zone because of controls and policing [8].

For a migrant seeking asylum at the border, it is difficult to distinguish between the army at the border, the police, the police-recruited border hunters, the normal border guards and, finally, the independently run border militias, equivalents of the Minutemen on the U.S.-Mexico border. These “Field Guards” (mezőőrök) are mostly directed by the mayor of the small village of Ásotthalom on the Hungarian side. The mayor has evolved into something of a celebrity of the European extreme right, having declared his village a Muslim-free zone and ardently posting pictures and videos of the captured migrants on his Facebook page, naturally with both English and Hungarian descriptions. His “field guards” are equipped with official-looking uniforms and cars, not only by the aforementioned Mayor but also by supportive “fans” who send migrant-hunting equipment from as far afield as Germany, Sweden and Finland.

A morbid voyeur would not need to go all the way to the border to witness the debasement, as the police assiduously upload pictures and videos of the people they have caught onto their social media and websites. Through social media, the political aesthetics of the fence permeate the entire country, saturated with references to control and masculinity. Directed at domestic and international audiences, these messages would be empty without the fence as their stage. The fence, then, also functions as a crucial apparatus in the Hungarian government’s quest to lead a conservative and Christian European Union that believes in closed borders and a Huntingtonian clash of civilizations.

For a different perspective, one might look at the numerous reports by Hungarian and international human rights organizations documenting hundreds of cases of violence and beatings of migrants at the border. Meanwhile, international, rotating backup border guards from other EU member states stand guard apparently oblivious to the violence taking place at the very border where they are posted. Not everyone, however, is happy about the continuous presence of police. In a recent TV interview, some people living in the border area have complained of insurmountable difficulties, reporting that everyday life has become unbearable as a result of the loud day and night presence of the police and the constantly jabbering fence. They are taking legal action and considering moving away.

The price tag of the fence is distributed and covered through a plethora of intertwined budgets. The fence itself is paid for by the Hungarian government, estimated recently at 284 billion Hungarian forints, or about 900 million euros. But it is a whole other thing to add on estimates for the costs of the accompanying transit zones where people are detained — the complex border agencies, the salaries of the border hunters, the provisions for the propaganda videos of the government and so on. Aside from the structure of the fence, much of Hungary’s asylum-processing infrastructure and functions were essentially transferred to the border zone, to which legal and human rights NGOs have limited or no access. Most functioning open refugee camps all around the country were closed, and the aim to transfer all asylum seekers in the country to the detention centers at the border was more or less accomplished. The border now constitutes its own special economic zone.

Most of all, however, the fence is a powerful stage, a set for the government’s incessant antimigrant, islamophobic campaigns waged ever since the Charlie Hebdo terror attacks in Paris. The colorful, visually appealing propaganda materials with retro fonts permeate the lifeworlds of Hungarians through government-financed “societally directed advertisements” (társadalmi célú reklámok). These take the form of billboards, posters, print media advertisements, brochures distributed to homes, border hunter recruitment videos and, of course, TV commercials, preferably with a dramatic soundtrack. The short mini-action videos on the Facebook page of the prime minister would not be complete without heroic shots of border guards at the fence protecting the nation from migrants. For how could Hungary stand as the last bastion against the creeping destructiveness of liberal, western multiculturalism without being an actual bastion?

This propaganda pulsates through all of society, across generations and institutions, and acquires a life of its own. Not long ago, the winning entry in a primary school drawing competition in a rural municipality turned out to be a drawing of nothing else than the fence along with a border hunter and a dog, painted by a little girl. Shortly after, a video that shocked much of Hungarian society showed children in a Transylvanian carnival celebration dressed up as a border hunter and a Syrian migrant. For the amusement of the audience, the children were reciting a witty, elaborate poem, presumably written by their parents, on the sneakiness of migrants who slink through the fence in search of money and social benefits [9].

What is often forgotten is that the fence — like some other border structures, including the U.S.-Mexico wall — is not, in fact, situated precisely on the border line. It is safely tucked a few meters on the Hungarian side. This minor cartographic feature of where the border actually lies is quickly forgotten in the government-sponsored action clips about the fence. Intriguingly, however, the fence carries a traumatic historical memory, for it actually runs along the state borders of Hungary as set by the Treaty of Trianon in 1920. Following the First World War, Trianon meant that Hungary lost two-thirds of its territory and a third of its population remained outside the borders that the fence now partly delineates. The national shock and trauma of the partitioning was powerfully visualized at the time, depicting vile hands tearing apart the national land, leaving only what would be known as Csonka-Magyarország, truncated Hungary.

A visitor to Budapest these days may observe such visualizations of Csonka-Magyarország on bumper stickers, fridge magnets and the like. In an uncanny manner, the speaking fence cements this disparaged delineation as the border of Hungary. The upshot of the fence is that many migrants now attempt to cross into Hungary from Romania. It remains to be seen whether the government will fulfill its pledge to possibly continue the fence onward along the Eastern border. Ironically, such a move would sever Hungary from Romanian Transylvania, considered by the government as the heartland of Hungarian culture.

Notes

1. Recording available at https://soundcloud.com/g-bor-medvegy. Accessed May 24, 2017.

2. Term coined by the Hungarian government in their public communications. See also Prem Kumar Rajaram, “Europe’s ‘Hungarian Solution,’” Radical Philosophy, no. 197 (June 2016): 2–7.

3. Dace Dzenovska, “Eastern Europe, the Moral Subject of the Migration/Refugee Crisis, and Political Futures,” Europe at Crossroads: Managed Inhospitality, March 2016. Available at http://nearfuturesonline.org/eastern-europe-the-moral-subject-of-the-migrationrefugee-crisis-and-political-futures/. Accessed May 24, 2017.

4. Sarah Collinson, “Visa Requirements, Carrier Sanctions, ‘Safe Third Countries’ and ‘Readmission’: The Development of an Asylum ‘Buffer Zone’ in Europe,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 21, no. 1 (1996): 76–90. doi:10.2307/622926.

5. Annastiina Kallius, “Rupture and Continuity: Positioning Hungarian Border Policy in the European Union,” Intersections. East European Journal of Society and Politics 2, no. 4 (December 21, 2016). doi:10.17356/ieejsp.v2i4.282.

6. Prem Kumar Rajaram and Carl Grundy-Warr, eds., Borderscapes: Hidden Geographies and Politics at Territory’s Edge (Minneapolis: Univ Of Minnesota Press, 2007).

7. Raia Apostolova, “The Real Appearance of the Economic/Political Binary: Claiming Asylum in Bulgaria,” Intersections. East European Journal of Society and Politics 2, no. 4 (December 21, 2016). doi:10.17356/ieejsp.v2i4.285; Céline Cantat, “The Ideology of Europeanism and Europe’s Migrant Other,” International Socialism, no. 152 (2016): 43–68.

8. Martina Tazzioli, “The Government of Migrant Mobs: Temporary Divisible Multiplicities in Border Zones,” European Journal of Social Theory, July 26, 2016, 1368431016658894. doi: 10.1177/1368431016658894.

9. Video available at http://indavideo.hu/video/Gyerekek_farsangja_migranssal_es_rendorrel. Accessed May 24, 2017.

~~~

Annastiina Kallius is a doctoral candidate in Social and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Helsinki. Her research looks at the shifting locations of Hungary in Europe through the lens of migration, and her interest is directed toward questions of postsocialism, modernity, location, borders and migration.

One Response

nice