On August 25, 2016, the National Park Service (NPS) will celebrate its 100th birthday. But what’s a party without people? In fact, while many Americans think of national parks as places to experience nature, they also preserve unique resources that tell stories about the everyday lives of people and their American journeys.

Along with protecting natural wonders, such as Yellowstone National Park’s geysers, the National Park Service is charged with preserving cultural resources that are relevant to living communities. Many of the more than 400 sites in the national park system are repositories of history and heritages of people and communities – some well-known, others underrepresented – that shape the national dialog. Particularly in recent decades, NPS has worked to showcase a diverse range of human stories that help us understand our nation’s past and present.

Today NPS’ role in cultural heritage preservation – collecting and interpreting stories about people and the many ways they inhabit places – is more important than ever. These stories help us to see our similarities and better understand our differences as a society. And this work helps NPS tell a national story of relevance and significance to all.

Telling diverse stories

Our national park system includes many of our nation’s most important and, in some cases, most contested cultural sites and resources. Examples include Historic Jamestowne, where English colonization of North America began; the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, which commemorates the forcible removal of the Cherokee people from Georgia, Alabama and Tennessee; the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument, which honors Tubman’s heroic work leading enslaved people to freedom; and the Manzanar National Historic Site, one of 10 camps where Japanese-American citizens were interned during World War II.

Most recently, on June 24, 2016, President Obama designated the area around the Stonewall Inn in New York City, where protests sparked the movement for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender rights in 1969, as a national monument.

Each of these sites links our nation’s past and present in challenging and enriching ways. As a cultural anthropologist, I work with the National Park Service to involve underrepresented communities in interpretations of place and to ensure that our park system embraces and reflects diverse experiences.

This work is not just about written history and preserving the past. The National Park Service’s Ethnography Program, created in 1981, focuses on “living people linked to the parks by religion, legend, deep historical attachment, subsistence use, or other aspects of their culture.” Through consultation and research, the program works to ensure that voices and practices of these communities are heard and taken into account in decision making and administration of National Park Service sites.

Conserving objects and experiences

For example, in 2010 I conducted research in rural southeast Georgia with students from the University of South Florida (USF) focusing on the community of Archery. Our study documented Archery’s roles as the boyhood home of former President Jimmy Carter and home of Bishop William Decker Johnson (1867-1936), who was a prominent preacher, educator and founder of the Johnson Home Industrial College, which started in 1912 in Archery as a school for black youth. Archery is also the site of the St. Mark African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church, Johnson’s home congregation. St. Mark represents the heart of the historically African-American community that constituted the majority of Archery during President Carter’s boyhood.

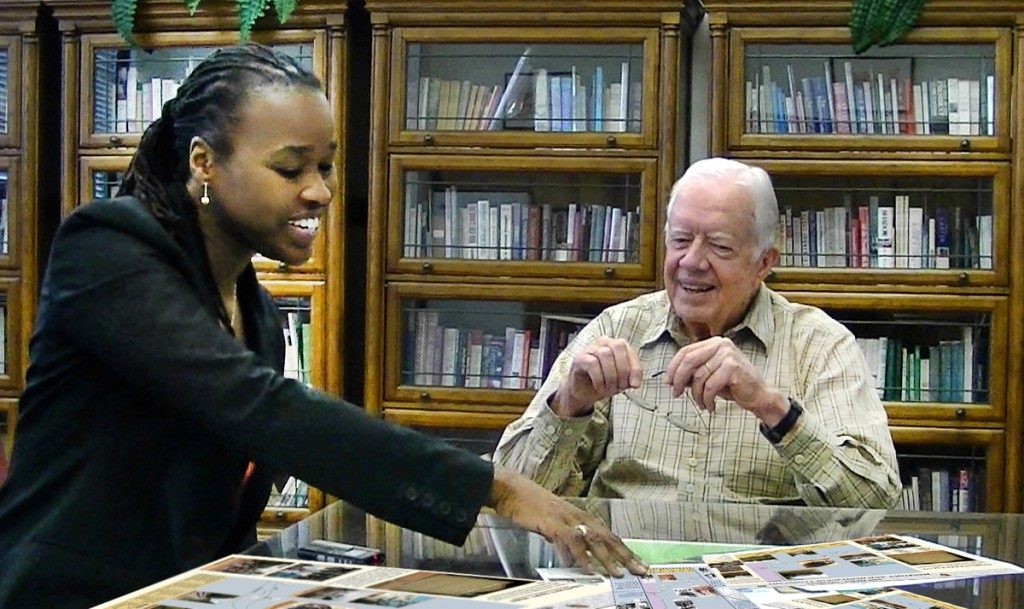

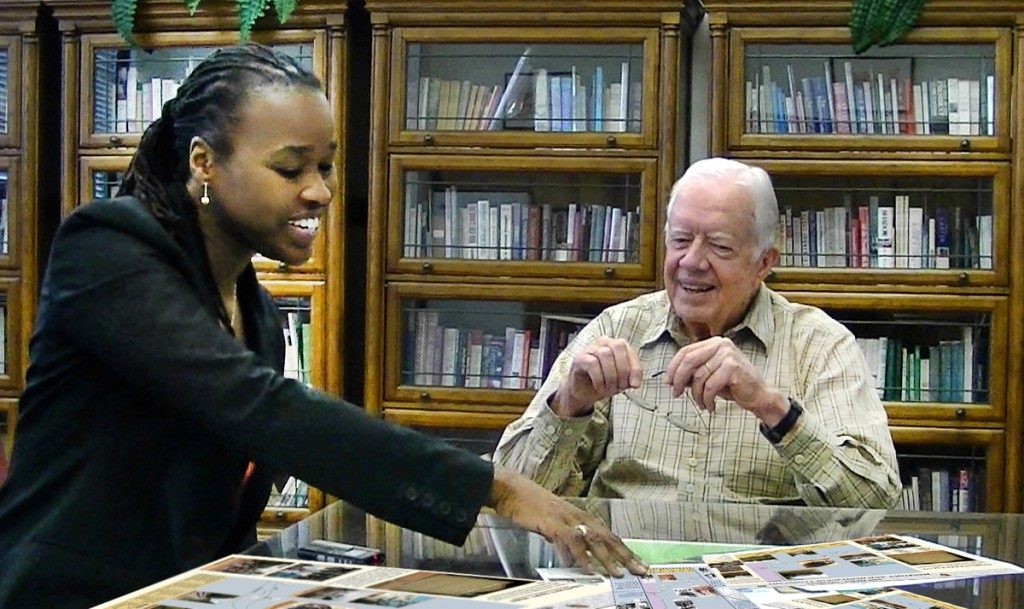

We used tools and methods that encouraged participation and enabled people to share their stories. This included conducting interviews and collecting oral histories from former residents of Archery, including President Carter. In addition, we participated in community events like the annual May Day festival and visited with people in their homes, businesses and churches.

We documented stories about farming, fishing, segregated schooling and special events like family reunions, baseball games and train rides. And we linked these stories with material culture findings, such as photographs, remains of old buildings, abandoned wells and gravesites, and with places such as train depots, baseball fields, ponds, pecan groves and pine tree stands. Together they tell a story about a small community in rural Georgia that has national significance.

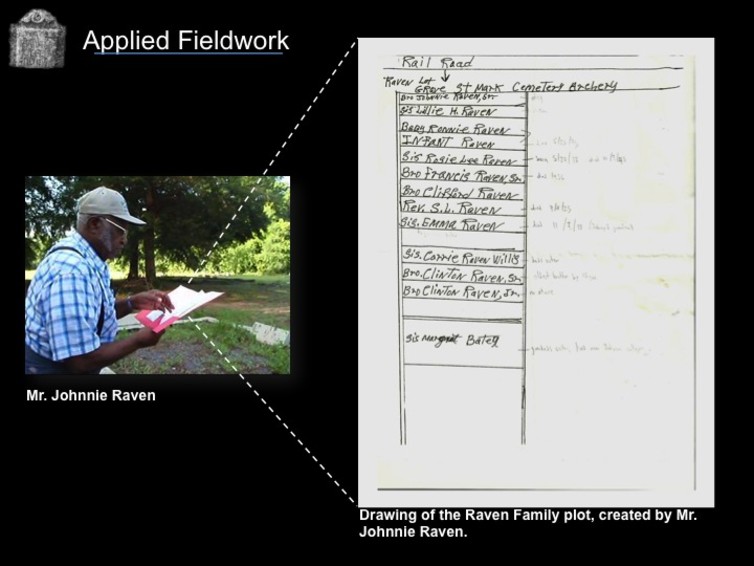

Our team also translated some of the stories and information collected into maps, posters and other visual and digitally accessible products in order to showcase the community of Archery to people who were unfamiliar with its history and heritage. For example, with the help of community elders, we surveyed the St. Mark A.M.E. Church cemetery and identified nearly 200 graves, some of which had previously gone unmarked. We created a detailed map of the cemetery with associated names, and a geographic information system (GIS) database that digitally displays information listed on each grave marker and shows a picture of each gravesite.

As Archery continues to work on preserving its past and securing its future, preservation and management of the cemetery should remain a key goal. It is an integral part of the Archery community. For example, it allows us to see multigenerational connections and extended family histories and reflect on them, such as those of Zenobia Wakefield, (1867-1962), midwife and member of a founding family of the community, and Bishop William Decker Johnson. The cemetery links the past to the present in tangible and intangible ways.

Our cemetery mapping work, ethnographic interviews and other community engagement activities pursued as part of this project demonstrate the power of incorporating community knowledge into cultural resource management and heritage preservation initiatives. The National Park Service cited our ethnohistory study of Archery in its 2015 Call to Action plan, which pledges that in its second century, the park system will “fully represent our nation’s ethnically and culturally diverse communities” and help communities protect places and objects that are special to them.

Our Archery community project materials are archived at the Jimmy Carter National Historic Site in Plains, Georgia and are on display at the St. Mark A.M.E. Church. Our maps and posters can also be accessed via the USF Heritage Research Lab.

What places can tell us

As our work in Archery shows, we can find unique and precious connections to our past in seemingly unassuming places. In his book “Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language Among the Western Apache” (1996), anthropologist Keith Basso captures what places can mean to people and how people help us know places. Basso writes that:

“places possess a marked capacity for triggering acts of self-reflection, inspiring thoughts about who one presently is, or memories of who one used to be, or musings on who one might become. And that is not all. Place-based thoughts about the self lead commonly to thoughts of other things – other places, other people, other times, whole networks of associations.”

Wisdom does sit in places, and in stories people tell about those places, and the lives people live in those places. Perhaps we should reconsider the artificial lines that we often draw between natural and cultural resources, between tangible and intangible cultural resources and between historic resources in museums and the knowledge we can find within communities, families and their lived experiences.

The national park system provides a window into stories about places, people and experiences. This makes it, and NPS’ cultural resources and heritage preservation programs – particularly those focused on engaging living communities – invaluable assets for educating future generations. We can learn as much about our American journey from people such as Bishop William Decker Johnson and communities such as Archery as we can from experiencing the Grand Canyon or the mountains of Yosemite.

Antoinette Jackson is an Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of South Florida in Tampa, and is the Director of the USF Heritage Research Lab. She receives funding from and is affiliated with the National Park Service, and was the Southeast Region Cultural Anthropologist for the NPS until May 31, 2016.

*This article was also published online at theConversation.com

2 Responses

This article gave me a better understanding of the NPS and the value of the role it plays in the preservation of our history. I have been inspired to take some time and explore more historical parks as I travel in the future.

Thank you Antoinette Jackson for sharing your knowledge to enlighten us.

I learned a couple of things from this article! First I did not know He was from Archery, Georgia. Thats cool that their preserving those historic sites!