Lissa: A Story about Medical Promise, Friendship, and Revolution tells a tale in graphic novel form of two (fictional) girls, one American and one Egyptian, who each faces different medical dilemmas. Set largely during the Egyptian Revolution, it reveals through the personal stories of the two characters — composites invented by the authors and drawn from their respective fieldwork — a lot about tough choices that people in the two countries must make about medical care. It was written by two anthropologists, Sherine Hamdy and Coleman Nye, with art by Sarula Bao and Caroline Brewer, who were two seniors in comic arts at the Rhode Island School of Design when they were recruited as the artists for this project.

Its authors, following Paul Stoller, who followed Jean Rouch’s lead, call it an “ethno-fiction.” The story and characters themselves are fictional, strictly speaking, but the historical and political settings are not. The real and the fictional overlap and interpenetrate in multiple ways, including the use of graffiti and graphics from the Egyptian Revolution generously provided by the artists. Although an ethno-fiction, it is something that could not have been invented without the authors’ deep knowledge and fieldwork, and without their collaboration with Egyptian colleagues. As a reviewer/evaluator, I have nothing but admiration for this book. The story is compelling — even a page turner. Moreover, it is informative, historically and culturally situated and uplifting — or, at least, it ends on a hopeful note — teaching hard truths, or glimpses of them, in an accessible and digestible way. Contemplating the task of reviewing this book and saying more than yay or nay, however, brings to mind my colleagues the multispecies anthropologists, as well as some ideas in Ian Hodder’s book Entangled. What I mean is that this book should not be approached as an autonomous free-standing object, but rather as a node in a network of relations, an entity constructed and related to its ecology of publishing, authorship, audience and more. Its internal structure (the graphic novel form) and content and references (its historical references and setting, the authors’ fieldwork), likewise, are entangled and layered.

I’ll discuss some of these ecologies and networks of entangled forms (the project of publication, the graphic novel as a form, the emerging genre of graphical medicine, the special virtues of comix as a narrative form), and will finally comment on blurred genres or mixed media and Lissa’s place on the expanding margins of conventional anthropology. I’ll often use the cartoonist Art Spiegelman’s term comix, or the co-mix of words and images, and Will Eisner’s term sequential art, in lieu of terms I like less, such as graphic novels or comics. Spiegelman and Eisner are both theorists as well as practitioners of comix and sequential art.

Lissa, the Publication of a “Graphic Novel”

Lissa is the first book of the University of Toronto Press’s new series called EthnoGRAPHIC, which will be a series of books in graphic form. The next scheduled book in the series (coming out in Spring 2019) is Gringo Love, a graphic novel about sex tourism in Brazil — a topic rich for exploration of issues of class, race and fantasies. The following fall, they have scheduled one called Heshima: Islam and Friendship on the Swahili Coast, which by its title also sounds fraught with hard issues. UTP’s is an admirable vision — to depict difficult topics in accessible ways, with lots of resources on the web and published in the book itself, to allow readers easy ways to deepen and extend their understandings of the nonfictional backdrops of the stories they have just absorbed.

The impulse to publish this series comes in part from the vision of the anthropology editor, Anne Brackenbury, and the UTP’s Teaching Culture Series — an effort to produce high-quality and accessible materials, often with associated websites. EthnoGRAPHIC seems to roughly follow that model, except that the titles in it are promised to be rich in visual material and are aimed not just for teaching but for a wider public.

All published books require collaboration, but in this one, the complexity of the production and its references are made exceptionally visible. The book includes a lot of front and back matter to contextualize the story and its making in several ways: various interviews of the authors and other important contributors (Anne Brackenbury interviews Marc Parenteau, who coordinated and advised on layout and sound words; Parenteau interviews Hamdy and Nye (separately); Paul Karasik (eminent cartoonist on the faculty at Rhode Island School of Design who recruited the two artists for this project) provides the readers with an enlightening primer on how to read comics; the anthropologist George Marcus writes a short piece about the “transduction” of Lissa. Other back matter includes a timeline of the Egyptian revolution integrated with the story, study questions, and a bibliography of further reading and films/videos and website resources on topics related to the story, from the Egyptian Revolution to graphic memoirs of illness.

As a person who makes humorous line drawings myself (can’t call myself a cartoonist, since my drawings are rarely sequential), I was disappointed that the artists were not interviewed for the book’s back matter, but they are vividly present in the documentary film that will be released about the making of Lissa by the filmmaker Francesco Dragone. He followed the collaboration and the collaborators both at home and on a short trip to Egypt, undertaken so that the artists could experience Lissa’s setting and ambience. On that trip also, the group contacted some of the Egyptian artists and doctors who were active in the Revolution, some of whom appear as nonfiction characters in the ethno-fiction.

In short, producing this book and its associated material was a huge effort of intelligence, knowledge, love and good spirits, not to mention hard work and financial support. So, let’s not forget the sponsors: key parts of it were funded by the Watson Institute of RISD and by the Luce foundation.

Graphic Novels

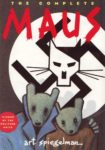

L issa is a “graphic novel,” a term loosely applied to a story (fiction or nonfiction) told in comix style, which is to say sequential panels combining words and images. Graphic sequential art on serious and nonfictional topics has been emerging as a genre for some time — one remembers the shock of Art Spiegelman’s now classic and genre-bending Maus, the account of his father’s recollections of his life in concentration camps. The shock and initial controversy of Maus was in reading a nonfiction story about an experience in the Holocaust told by an underground comix artist in a form that was most widely associated with superheroes or cartoon characters for children. (Not until maturity did one realize after reading Ariel Dorfman’s How to Read Donald Duck [1971] that Donald Duck and Babar were part of the capitalist and imperialist conspiracy. Oh, well.)

issa is a “graphic novel,” a term loosely applied to a story (fiction or nonfiction) told in comix style, which is to say sequential panels combining words and images. Graphic sequential art on serious and nonfictional topics has been emerging as a genre for some time — one remembers the shock of Art Spiegelman’s now classic and genre-bending Maus, the account of his father’s recollections of his life in concentration camps. The shock and initial controversy of Maus was in reading a nonfiction story about an experience in the Holocaust told by an underground comix artist in a form that was most widely associated with superheroes or cartoon characters for children. (Not until maturity did one realize after reading Ariel Dorfman’s How to Read Donald Duck [1971] that Donald Duck and Babar were part of the capitalist and imperialist conspiracy. Oh, well.)

As could be expected, Maus was controversial: Some critics objected mightily to using a “comics” form for a topic as serious as the Holocaust. Published as a serialization in the underground comix RAW and spanning a decade or so, Maus as a serial ended in 1991, and Spiegelman received the Pulitzer Prize in 1992, the first comix artist to be awarded it. Another landmark: Marjorie Satrapi published her memoir/autobiography Persepolis (2003 in English) about leaving Iran after the Revolution of 1979 and finding a life in Europe. It was reviewed in serious journals like the New York Review of Books; it received many prizes; and a movie was made from it.

More recently, in 2014, the New Yorker cartoonist Roz Chast published Couldn’t we talk about something more cheerful? a cartoon depiction of her experience taking care of her aging parents from Brooklyn. By 2015, it had gathered many prizes and of course was widely praised. These were landmarks in the emergence of appreciation and popularity of this form, but there are many more nonfiction graphic novels and memoirs out there. It seems it is a burgeoning industry/genre. And it is not just for storytelling. Didactic comix, even in anthropology, have appeared, such as Sally Galloway’s Shane the Lone Ethnographer (2007). Comic Art Studies (yes, it is a field!) programs use as texts Eisner’s Comics and Sequential Art (1985 and 1990) and Scott McCloud’s semiotically explicit Understanding Comics (1993), and will soon no doubt use Paul Karasik’s How to Read Nancy (2017).

Lissa and Medical Graphics

Graphics and sequential arts are increasingly used in medicine — as art therapy, as memoirs of illness, for instructions to patients, and for at least one manifesto — read about it at graphicmedicine.org. It is my impression that the major impulse behind the use of graphics in medicine is for individual therapy and curing. Drawing your experience on paper, as a veteran with war trauma, for example, allows you to process the experience, as does writing/drawing a memoir of your experience with cancer. Quite a few of these comix function as a kind of advice or therapy for those who suffer from particular maladies, to help them negotiate the system, understand their illnesses and not feel alone. Lissa is related to this use of graphic stories, and my guess is that it will be welcomed by medical anthropologists and practitioners of medicine alike; but it is far less about personal experience and far more about social and political context than the others I have seen.

Lissa distinguishes itself from many of the medical graphic medicine accounts that I have viewed in that the story is embedded in hard larger truths. It touches on social class, imperialism, transnational labor migrations, the inadequacy of medical access in poor counties, the privatization of medicine in the U.S., the supposed “fatalism” of people who refuse high-tech medical intervention, international capital, oil extraction and militarization. The authors also intended to provoke readers to reflect on the contrast between different views of “the body” in Egypt and the United States. Layla’s father’s decision to refuse an organ transplant for his kidney failure, we come to understand, is because it would compromise his children’s future health, and besides, the follow-up treatment is likely to be beyond the family’s means. Getting a new kidney would put off his death for a while, but it would further impoverish his family and endanger their future.

Anna’s decision to have preemptive surgery for breast cancer, by contrast, is construed by her and her culture as an individual decision concerning her individual body. The device of using the accessible narrative form of comix about fictional characters from two different cultures allows the authors to tack between the particulars of individual experience and larger systems that are given, rather than to focus just on individual pain and curing. The title of one of Hamdy’s articles in the bibliography perfectly illustrates the juxtapositions and conjunction of personal and political in the author’s approach: “When the State and Your Kidneys Fail: Political Etiologies in an Egyptian Dialysis Ward.”

Lissa and Sequential Arts

In some ways, sequential art is like the movies. The cinematic quality of the narrative is clear on Lissa’s first page, which is organized as four big “rows” of horizontal panels. It begins with a panoramic long shot of a layered silhouetted cityscape, moving from a dark gray foreground to light gray pyramids at the back, signifying its location as “Egypt.” The next panoramic panel zooms in on an overpass crowded with cars. The third row consists of a pair of panels: in one, a slightly overhead shot of men in uniform with a partially visible police vehicle in the background; in the panel next to it, the camera moves down to nearly eye level and a more perspectival shot shows a row of men in camouflage, holding guns and apparently looking around alertly, the soldier nearest to us looming large and ominous. The bottom panel shows a fragmented collage of brick walls with posters of the Egyptian leader and a military officer. This first page, then, functions as an establishing shot, locating us in a highly urban militarized city in Egypt whose walls are apparently plastered with images of strongmen.

Pages two and three, equally cinematic in structure, introduce the main characters, their friendship and a medical crisis. The first panel on page two shows a telephone pole with a picture of Mubarik, and a footnote reveals that we are in “a quiet green suburb south of Cairo,” which sounds upper middle class. A telephone line runs from the pole into the second panel, spanning them, passing across tropical trees, and attaches to a particular house. In the third horizontal field down from the top, we find ourselves inside that house viewing two juxtaposed panels. In the first, the telephone line has entered a room in the house, and we see a table with a telephone where a person, head cut off in the frame, hears a word bubble “Stage 4.” The panel next to it frames a close-up of a hand near to the bottom of a closed door with the word “:sigh:” coming from behind it. In the fourth and bottom panel the camera pulls back to a medium shot of two girls crouched at the door hearing the words “Surgery is not an option. It’s already spread.” The facing page continues this cinematic unfolding, the “camera” again moving back and forth to close-ups of hands, an extreme close-up of eyes with tears, and uses over-the-shoulder shots to reveal the faces, separately, of each girl. The bottom right panel shows them hugging and the Anna character sobbing (“:sob:”). We eagerly turn the page to see what happens next.

These three initial pages of Lissa, then, are structured like cinema, using its language without using a camera. But cinema and comix are different. Movies are basically compulsory: Their relationship with the viewer is not to let up, to keep the viewer sitting on the edge of the seat, transfixed, from beginning to end. (OK, I exaggerate, but I’m making a point.) Comix, by contrast, intrinsically require more audience participation, and I think of them as having more breathing space. For one thing, they necessitate interaction, not just for turning the page but for interpretation.

As Scott McCloud points out in Understanding Comics, the gutter — the white space between panels — forces the reader to participate imaginatively in the narrative by linking panels across the gutter. Paul Karasik makes other devices explicit in his forward to Lissa — such as the way that the layout of the page helps to constitute rhythm and meaning, like the magnificent scene in the airplane when Anna seems to listen to voices advising her about her possible decision to have a preventive mastectomy. In addition, the narratives of comix are permeable. Readers can put the book down or turn the pages at their own pace, can go back and reread, can skip to the end. Perhaps most important for ethno-fiction, readers can pause to read a footnote or look something up in the appendices or even read an article or a website to enrich their understanding of the story. My guess is that, first time through, that won’t happen: The story is gripping, and it is artfully arranged to be a page turner. But the reader can revisit it many times at leisure, interrupting her attention to the story and deepening her understanding by using the material provided in this book itself, the web or the library.

Another semiotic feature of comix to note is that they are not “realistic” — they are less like what the art historian E.H. Gombrich in Art and Illusion called “illusionistic” or “perspectival” art (rationalized if not actually invented in the Renaissance) and more like “conceptual” or “schematic” art, or what C.S. Peirce would have categorized as diagrams, a subtype of iconic signification. Schematic art is generalizable. That’s the reason that signs in airports indicating “elevators” or “luggage” use a diagrammatic rather than an illusionistic style: a diagram can stand for all types of luggage, not a particular brand or shape or color. In Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud asserts that we can easily identify with a cartoon character precisely because it is not a portrait of a specific person. “A cartoon,” he writes, “is a vacuum into which our identity and awareness are pulled … an empty shell that we inhabit which enables us to travel in another realm.” McCloud calls the power of cartoons “amplification through simplification.” It lets us focus on the message rather than the messenger, he says.

The point applied to Lissa is that Anna and Layla, composite-fictional to begin with, are even more powerful as characters because they are cast as cartoons, as diagrams. Layla’s dilemmas are not just those of a particular historical Egyptian. We can project ourselves imaginatively and empathetically onto her cartoon character while also understanding her to be an emblem of the intersection of poverty, social class, views of the body in Islam, family ties and understandings, doctoring, sorrow and hope.

The most extreme form of a diagram would be a happy face or an emoji, and it is possible to draw a cartoon story with little more. Yet for a real cartoonist telling a story, a stick figure with an emoji face is generally too general. For a rich story, the cartoon schematic characters need also to be identifiable as individuals or as members of a group or category. Wayang kulit, the shadow-puppet theater of Java and Bali, is a dramatic form using schematic forms of representation. In wayang, figures of high status all have essentially the same face — elongated skinny torsos and noses, chin titled down, eyes looking down — whereas the category of raksasa or monster has bulging eyes, a large body, wild hair, and big teeth. Individuals of high rank (Arjuna, Sita) can be differentiated from others of their rank by their distinctive head ornaments and ear decorations.

In Spiegelman’s Maus, categories of people are drawn the same: The Jews are drawn as mice, the Nazis as cats, and so forth. This cartoon solution allows him to identify categories while avoiding stereotyping actual faces — think what a disaster it would be if he had drawn stereotypes of Nazis or of Jews. In Maus, particular individuals are distinguished by a certain item of clothing they wear. In one brilliant instance, Spiegelman draws a Jewish mouse-woman who in real life looked “too Jewish” to pass easily for a Pole, with her mouse-tail peeking out from behind her floor-length dress.

Lissa’s artists use yet another device: One artist drew Layla, the other, Anna, and their drawing styles are different. (Admittedly, so are the girls’ hairdos and skin color.) Aside from letting us immediately differentiate the girls, the two styles of depiction speak to the girls being from different cultural worlds. Toward the story’s end, as Anna’s and Layla’s lives intersect and their friendship deepens, the two styles grow subtly closer — as the artists (we are told elsewhere) switched the character that they were responsible for drawing. Interesting, too, is that when “real” people are depicted — political leaders, heroes and martyrs of the Revolution — the drawing style becomes more “realistic,” a stylistic and therefore semiotic move that allows the reader to understand that the story is set in real time and real space.

One more thing about the power of comix over the more “realistic” medium of cinema: You don’t need to actually blow up a car, or have stunt men, or have elaborate technology for special effects. You can depict your fantasies at no cost to speak of, making comix creation more financially feasible than filmmaking.

Even more to the point, the ability to depict in drawings things that do not exist or cannot be captured with a camera is precisely what makes comix powerful as medical art therapy: A patient, depicting his pain on paper, can show with a stroke of a pen his guts spilling out of his torso, or her head dissolving in tears, or her body bloated or shrunken, expressing their own visions of anguish. Frida Kahlo did that to show her own pain, prompting Andre Breton to welcome her as a surrealist; but she said she was not a surrealist and did not paint dreams or nightmares, but her own reality. Drawing and painting are wonderful devices for self- expression and for conveying emotions invisible to onlookers.

Lissa: A New Path?

Does Lissa forge a new path, “instructing anthropologists and academics more broadly in remaking their work in new forms,” as George Marcus claims in his short commentary included in the published book? At one level, sure: Although Lissa does not strike out in an entirely unknown direction, you could certainly say that it is expanding the margins of what has been tried. Those margins have been expanding for some time. Looking at the past 30 or 40 years of anthropology and other human sciences, genres have been blurring (to refer to Clifford Geertz’s essay of that title) for decades, at least from the mid-1980s with Writing Culture (1986) and so on. The style revolution (or so I think of it) brought consciousness to the fact that the form in which knowledge is cast is not its secondary qualities, like icing on the cake of facts. Style and medium shape, indeed are constitutive, of a work’s meaning.

Experiments that use visual material and may span anthropology and art (or at least artfulness or artiness) have increased in both market share and credibility, especially in this century, since digital media became pervasive and anthropologists became keener on outreach and accessibility. The annual programs of the Society for Visual Anthropology, which used to be dominated by ethnographic films with explicit arguments, began showing documentaries made by anthropologist filmmakers (they used to be separate and required collaboration) that use the visual language and plot structures of narrative films, including climaxes and resolutions.

Ethnographic Terminalia, an exhibition of artwork by anthropologists and others who create art, has become an institution at the AAA. It would be fun to opine on reasons for anthropology’s expansions into nontextual forms, especially visual ones (and I did so in a review essay on Ethnographic Terminalia a few years ago). And lately I note a great interest in the body, in handmade nondigital forms that connect brain and hand, mind and body, knowledge and aesthetic sensibilities — that use pencil and paper as a tool in fieldwork and for the representation of knowledge. It was only a matter of time, as they say, before a graphic ethno-fiction would appear. It is fortunate that Lissa is so good because it launches what may become an increasingly usable way to cast and communicate knowledge — ethnoGRAPHically.

~~~

Shelly Errington is a photographer and cartoonist, as well as being Emerita Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Her work can be glimpsed at shellyerrington.com and at shellyerringtonphotography.com. She’s always behind in keeping up her websites, though.