Perpetual War

Text by Katherine T. McCaffrey. Photos by Bonnie Donohue.

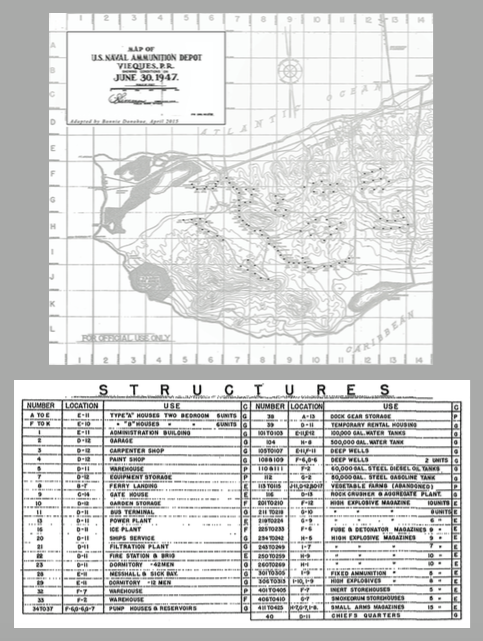

Vieques Island, Puerto Rico, is home to 107 abandoned military bunkers, a legacy of the U.S. naval presence on the island. Designed to contain ammunition and high explosives, the bunkers were constructed during the build up to WWII, when the German threat to the Western Hemisphere and U.S. control over the Panama Canal were paramount national concerns.

The bunker — that very dramatic manifestation of military power, of the primacy of military interests over civilian concerns, of the U.S. domination of Puerto Rico and indeed, the Western Hemisphere — embodies not only the dynamics of the past, but the continued domination of military interests in Puerto Rico and the way the U.S. Naval presence has distorted and continues to constrain Vieques’ social and economic development.

The U.S. Navy occupied Vieques from 1941–2003, using the eastern side of the island for maneuvers and live target practice and the western side for ammunition storage. A civilian residential population of 10,000 was wedged in the middle. Tension between these conflicting purposes — theater of war and civilian community–sparked protest over the years of military occupation and culminated in a powerful grassroots movement that drove the Navy from Vieques in 2003. I have conducted ethnographic and historical research in Vieques since 1991, examining the impact and legacy of the military occupation on the residents of this small island municipality.

Today, media coverage and political rhetoric focus on the catastrophic damage inflicted on eastern Vieques by decades of intensive bombing and live-fire exercises. The Navy left thousands of unexploded bombs and live ammunition on its former firing range and has now embarked on perhaps the largest military cleanup project in history. Less attention is focused on the western side of the island, which was used for ammunition storage, a small operational base and a radar installation. The west does not face the same overwhelming environmental challenges as the east, although there are a number of toxic sites there. The defining feature of the west is the dozens of bunkers that cut like boot treads into the quiet, mostly empty landscape.

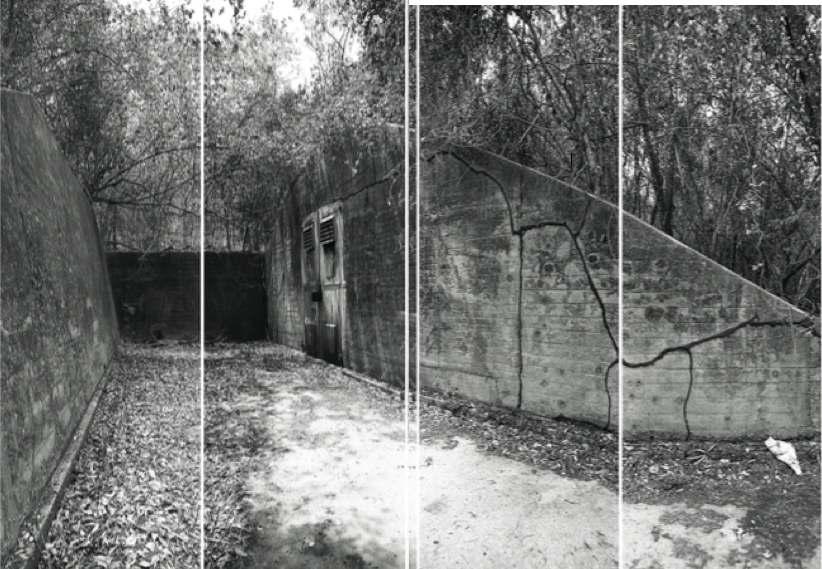

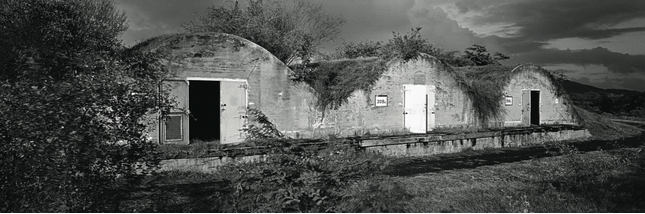

The bunkers themselves pose unique problems for a demilitarized Vieques. Built to resist destruction, these fortified structures might be considered a kind of anti-ruin. In fact, one of the main problems with the bunkers may prove to be their endurance. The “igloo” type magazines the Navy built in 1942 are low, barrel-arched structures constructed of reinforced concrete and covered with earth. The design was developed in the aftermath of the infamous Lake Denmark, New Jersey, explosion in 1926. A lightning strike at that naval ammunition depot ignited a conflagration in which 19 people were killed and 50 more injured. The facility suffered nearly $50-million in property damage (equivalent to nearly $1 billion today). Missiles were catapulted more than a mile across the landscape [1]. As a consequence of that disaster, engineers designed a new barrel-arch magazine that would direct the force of an explosion up instead of out, and bermed earth upon the structure to mitigate the force of a potential explosion. One economical variation, the Triple-Barrel Vault, consisted of three standard igloos built side-by-side so that they shared walls, a foundation and a loading dock, thus conserving construction material that was in short supply during the war.

Ordnance depots consume vast tracks of land. Storing volatile munitions requires at least minimal distances between storage structures, and ammunition storage areas typically occupy between 10,000 and 20,000 acres [2]. In the early part of the 20th century, Vieques’ western land was the heart of the island’s sugar economy. Hundreds of workers migrated seasonally and permanently to Vieques to work in the cane fields. Small villages sprung up around the mills.

During a period of national emergency, the Navy expropriated 22,000 acres of Vieques land to build a major operating base. Thousands of people were evicted to make way for the bunkers. The seizure of this land was the death knell to Vieques’ economy. The island has never since reached the levels of employment witnessed during this period.

Today, Vieques’ land is still defined by World War II-era military strategy. The nature of warfare has changed and the U.S Navy has abandoned Vieques, but the bunkers remain. Hard to see from a distance, they are strategically camouflaged into the landscape, earth-covered to contain any unintended explosions. The igloo-style bunkers are designed to be missile-proof and immune to structural damage caused by an explosion at an adjacent magazine.

Vieques is one of many landscapes across the world littered with abandoned military bunkers. In Bunker Archaeology, the French cultural theorist Paul Virilio photographed and reflected on the enduring landscape of war in his native Brittany [3]. There the occupying German army built a vast coastal network of fortifications known as the Atlantic Wall in a failed bid to repel an expected allied invasion. Long after the war ended, these mammoth concrete and steel structures remain on France’s north Atlantic coast, despite the public’s desire to forget them and the painful history they represent. Virilio argues that these bunkers reflect a military strategy of entrenchment that has become obsolete as forms of warfare have evolved.

Yet rather than representing vestiges of a military past, the Vieques bunkers might be regarded as embodying the continued power of the U.S. military in Puerto Rican affairs. In 2005, three quarters of Vieques’ residents joined a class-action suit against the Navy, seeking financial reparations for health prob- lems residents allege are the legacy of 60 years of military live-fire exercises. Residents claimed that the Navy had a responsibility to warn them about potential health risks they had been subjected to by bombing. In 2010, however, a federal district court in Puerto Rico dismissed the suit, noting that the Navy enjoyed “sovereign immunity” in its military practices on Vieques Island. In 2012, an appeals court upheld the dismissal.

The concept of sovereign immunity is an expression of ongoing military power. This legal principle holds the sovereign, or government, immune from lawsuits or other legal actions except when it consents to them. It protects government bodies and employees from being sued in their own courts. One provocative definition declares: “Though commonly believed to be rooted in English law, [sovereign immunity] is actually rooted in the inherent nature of power and the ability of those who hold power to shield themselves” [4]. It seems that “sovereign immunity” allows the Navy broad “discretion” to carry out its activities without interference from the people it harms.

In practice this means that on the eastern part of Vieques Island, the Navy is actively cleaning up live ordnance that poses an immediate risk to human health, mainly due to the potential for detonation. This process is mandated by law and funded by Congress. But the cumulative health effects of long-term exposure to bombing are not addressed by the cleanup process and are not considered the Navy’s responsibility. The economic impact of closing down the island’s sugar mill and commercial ferry, the usurpation of its productive land and failure to pay property taxes, the stifling of economic opportunity by restrictions on construction, flight paths and water routes, are not subject to repair or compensation. Sovereign immunity protects the Navy from most tort claims connected to its activity.

The bunkers make these dynamics visible. Nowhere in any of the Navy’s exit plans are the bunkers mentioned. While the federal clean-up plan addresses toxic waste sites and unexploded ordnance, the bunkers do not represent a “risk” to human health, and are therefore beyond the scope of the envi- ronmental remediation process. Nonetheless, as they cut across hundreds of acres of once fertile farmlands, the bunkers present formidable constraints to development. These missile-proof concrete structures define and determine the future shape of the landscape. It seems the only way to remove them is with bunker-busting bombs, the most powerful conventional explosives in the military arsenal.

Interestingly, the otherwise comprehensive master plan for the sustainable development of Vieques makes only the slightest passing mention of the bunkers in its road map for restoring the island. The bunkers are offered up as potential sites of “hobbit housing” where tourists might stay overnight in blast-proof concrete coffins for a unique Caribbean get away.

Further complicating the resolution of this colonial legacy, the ownership of the bunkers is divvied up among three different entities — the municipality, the Puerto Rico Conservation Trust and the Department of Interior, all of which have different missions and thus different priorities on how to use these spaces. In the absence of any overarching strategy for conversion, the municipality has been using several bunkers under its jurisdiction to stockpile a growing mountain of obsolete monitors and tube televisions, creating a new toxic mess of leaded waste.

One bunker had a brief life span as a massive, 10,000 square-foot mega-nightclub. In 2010, the New York Times endorsed Club Tumby as a venue that “[drew] local 20-somethings and visitors almost literally to the middle of nowhere” [5]. Unfortunately for the Vieques club scene, the son of Club Tumby’s owner was imprisoned for trafficking cocaine and the bunker disco closed. In this way, Vieques’ colonial past as a pirate den, operating beyond the reach of state authority, is being revived by contemporary narco-traffickers, ironically repurposing structures intended as safeguards. Underpopulated and under-scrutinized, with an underpaid, under-staffed police force, Vieques emerges once again as the perfect base for illicit trade. Security concerns stand as an additional obstacle to reclaiming former military land.

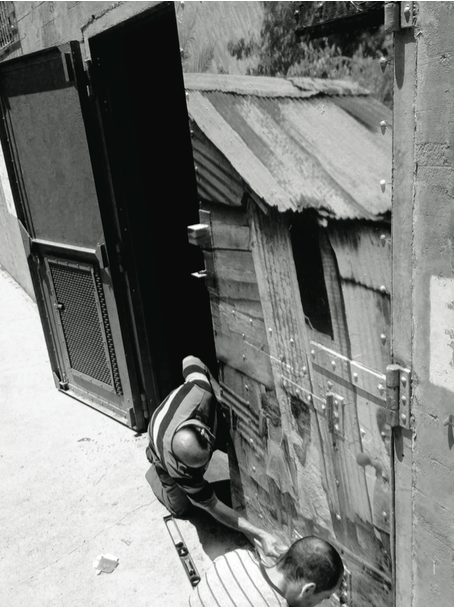

During the summer of 2014, Bonnie Donohue produced a public art installation on the site of one Vieques’ bunkers. The exhibit challenged the erasure of the past by installing life-sized archival photographs of the shacks, animals and families of sugar cane workers who were evicted to make way for the bunkers.

When we were on site installing the photographs, a car pulled up out of nowhere and a young couple from Puerto Rico emerged to evaluate the project. He was a fashion photographer for Victoria’s Secret scouting a venue for his next lingerie shoot. We wondered if Bonnie’s public art project, centered on historical memory, would be appropriated and sensationalized by commercial interests. Would gaunt models in lace underwear collapse against the steel bunker doors that she had meticulously scrubbed clean of rust and dirt?

The shape and trajectory of Vieques’ future is unfolding in a dynamic interplay with its rich past, a past punctuated by dramatic struggles — of Taino chieftains who launched devastating raids on Spanish outposts in Puerto Rico from Vieques and pirates who plundered ships from its shores. Vieques was the site of slave rebellions, worker uprisings and, most recently, the mass mobilization to evict the Navy. Its past bubbles up. As William Faulkner famously noted, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Aftermath: Architecture of War

by Bonnie Donohue

In 2004, after spending three years working on a video documentary about the protests against the Navy in Vieques, I took a break. I drove my rental Jeep to the western end of the island, which had been off-limits to civilians for many years, and found no barriers to access the landscape. Driving off the main path, I saw my first bunker: a surreal peachy hemisphere with huge steel plate doors, stencil-painted “Certified Empty.” Two or three feral horses, ubiquitous in the western end, were grazing on the roof. The scene took my breath away. I continued my exploration and found a total of 107 bunkers (magazines) in various sizes and shapes: small single-arch, large single-arch, large triple-arch, and trapezoid, each under thick and grassy sod roofs and each with its own chimney.

Those few hours in 2004 were to alter the course of my work in Vieques. The imposing structures would preoccupy my thoughts and direct my photography and research through the next decade. I dropped the documentary, and fell in love with the bunkers. I was struck by the paradox of the bunkers’ peaceful fa- çades and their violent histories. The bunkers conjure sustainability with their eco-friendly “green” roofs and unlimited sunshine, as if ready to go off-grid. In fact, from WWII into the Cold War and beyond, they stored implements of destruction, for U.S. military forces. In the National Archives and the Seabee Mu- seum archive I later discovered documentation of their histories, storing everything from small arms to warheads and high-explosives, the tools of escalating force over the decades.

Until a recent ordinance allowed some Viequenses to homestead there, the western end of the island has been mostly unpopulated, since the great evictions beginning in 1941. Between 1941 and 1943, the U.S. Navy expropriated the 10,000 acres in the west — all belonging to a single sugar baron — and moved thousands of sugar workers and their families from subsistence plots to razed fields in the center of the is- land. In a later expropriation of the eastern end of the island between 1947 and 1948, hundreds more citizens would be displaced to the center, along with thousands of heads of cattle, an industry that had grown to compensate the collapsed sugar economy. With little space left to graze, the cattle industry was undermined less than a decade after the sugar economy was destroyed.

I returned several times that year, and every year since, armed with a medium-format panoramic camera, to photograph the bunkers. Additionally, I combed dozens of archives, from San Juan to Santa Barbara, California, searching for evidence of citizens whose lives and livelihoods appeared to have been carefully erased from the history books.

The photographic and archival work between 2004 and 2006 resulted in my 2006 traveling exhibition Vieques: A Long Way Home [6], which weds archival photographic evidence with the residual warchitecture [7] that stands in place of the hundreds of homes that preceded them.

In August 2014, I installed two 8’ x 9’ photographs on the doors of Bunker #412 [8], both of which were taken in December 1941, just days before the Pearl Harbor attack. One of the photographs features the home of Ramón Rodríguez; his daughter Benedicta is standing at the door, having just been served an eviction notice, and his younger children are playing nearby. The second image is of the Navy assessor, Jaime Annexy, who was auditing the entire western end of the island for the purpose of the Navy’s expropriations. His team delivered the eviction notices to hundreds of the residents.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Robert Rabin, director of Museo Fuerte Conde de Mirasol in Vieques, for his unwavering support for their work. Additional thanks to Julián García and Fernando Lloveras of the Puerto Rico Conservation Trust, who support development of the bunkers; We warmly acknowledge the family of Ramón Rodriguez, whose home is the subject of the installation.

Funding

The authors would like to thank the Graham Foundation, who provided funding for the bunker project.

Notes

1. Joseph Murphey, Dwight Packer, Cynthia Savage, Duane E. Peter, and Marsha Prior. “Army Ammunition and Explosives Storage in the United States: 1775-1945.” (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Fort Worth District. Geo-Marine, Inc, Spe- cial Publications No. 7, 2000).

2. Ibid.

3. Paul Virilio, Bunker Archaeology (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 1997).

4. “Sovereign Immunity.” ‘Lectric Law Library. Accessed March 2, 2014. http://www.lectlaw.com/ def2/s103.htm

5. Hugh Ryan, “36 Hours in Vieques,” The New York Times, February 15, 2010.

6. Vieques: A Long Way Home was exhibited in 2006 at Museo Fuerte Conde de Mirasol (Vieques), and Biblioteca Lazaro at University of Puerto Rico’s Rio Piedras campus; in 2007 it traveled to Casa Escute in Carolina, P.R. and Villa Victoria Center for Latino Arts in Boston. Work from the exhibition was recently featured in Unending War: the Age of Constant Conflict at the Grossman Gallery, SMFA, Boston.

7. Andrew Herscher, “Warchitectural Theory.” Journal of Architectural Education 61, no. 3 (2008): 35–43. “The term ‘warchitecture’ emerged in Sarajevo as a name for the catastrophic destruction of architecture during the 1992–1996 siege of the city. Blurring the conceptual border between ‘war’ and ‘architecture,’ the term provides a tool to critique dominant accounts of wartime architectural destruction and to bring the interpretive protocols of architecture to bear upon that destruction. Reflection on warchitecture can therefore open up new ways to examine and understand violence against architecture and to connect this violence with emergent discussions of war, violence, and modernity in and across other disciplines” (p 35).

8. The semi-permanent installation is titled: Reclaiming Vieques: Memory and Imagination.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Gordillo, Gastón R. Rubble: The Afterlife of Destruction. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2014.

Mah, Alice. Industrial Ruination, Community and Place: Landscapes and Legacies of Urban Decline. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012.

Stoler, Ann Laura, editor. Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2013.

Bunker Archaeology. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Ar- chitectural Press.

Katherine T. McCaffrey is associate professor of anthropology at Montclair State University. She is the author of Military Power and Popular Protest: The U.S. Military in Vieques, Puerto Rico (Rutgers 2002). With Bonnie Donohue, she curated a photographic installation, “Killing Mapepe: Sex and Death in Cold War Vieques,” that showed at the Fuerte Conde de Mirasol Museum in Vieques (2011) and the Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts in San Francisco (2012). She is a founding editor of Anthropology Now and is pleased to be contributing to it as an author.

Bonnie Donohue is on the graduate faculty in studio art at The School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. She is a photographer and video artist whose work maps places of disruption, conflict and loss while examining race, class, economy, politics and cultural erasure. She carefully researches and documents these locations over time and works with ideas for art interventions. She is interested in locations where ordinary people, after years of displacement, have successfully united with a singular notion of reclaiming their patrimonial heritage from dominant forces.