uncommon sense

Spoiler alert: In Hitchcock’s masterpiece Psycho, Janet Leigh was not savagely murdered in the living room, but we’ll get to that.

Culture wars can erupt anywhere, including in the bathroom. These spaces are personal. They really can be dangerous, nerve-wracking and threatening, but not for the reasons we hear on the media. Today’s bathroom controversies reflect long-standing anxieties intensified by a rapidly changing world. They provoke passionate outcries in some quarters as they touch politicized raw nerves. In North Carolina, Texas, Indiana, among perhaps as many as twenty states, legislation was passed, is pending or has been revoked to secure the conventional order of binary, gender-discriminating bathrooms [1].

In spring 2016, bathroom space became especially problematic when state laws clashed with federal directives prohibiting discrimination based on sex. Bombast from conservative talking heads and irrational anxieties conjured by fantasies of harm amplified the situation in the media sphere. Political protests heightened deep discomforts more often kept in the water closet than aired publicly. A national furor ensued, but why?

A holistic, anthropological view helps to understand in a larger frame conservative distress over softening categories because the bathroom is the central space where beliefs and anxieties about gender, the body, identity, privacy and safety collide. It is a culture war waged over symbolic spaces reinforcing constructions of how we see ourselves privately and publicly. Most Americans match deep convictions about males and females with binary spaces to perform those necessary biological functions.

American insecurities with both bodies and bathrooms lie at the center of this situation. Today, more fluid views of gender challenge notions that everyone neatly fits a male or female stall, whether that stall is literal bathroom space or rigid categories of sex in a checked box on a birth certificate. Uneasiness over definitions of gender fuels excessive fear about that most personal of places. As anthropologist Gabriela Torres wrote in Anthropology News, “Gender . . . still lies at the center of many of our fears.” [2]

Sacred Liminal Space

The bathroom has long fascinated us. Sixty-two years ago, in his tongue-in-cheek “Body Ritual Among the Nacirema” (“American” spelled backward), anthropologist Horace Miner called attention to “ritual centers” or “household shrines” with their charm boxes above sacred fonts where individuals performed private ablutions with holy water. He noted the importance of the number of these ritual centers in ads for Nacirema homes, a feature that remains true today [3].

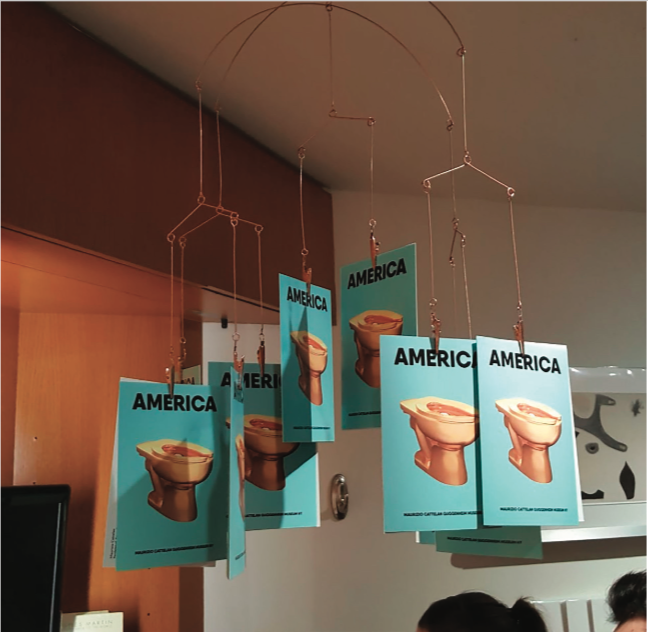

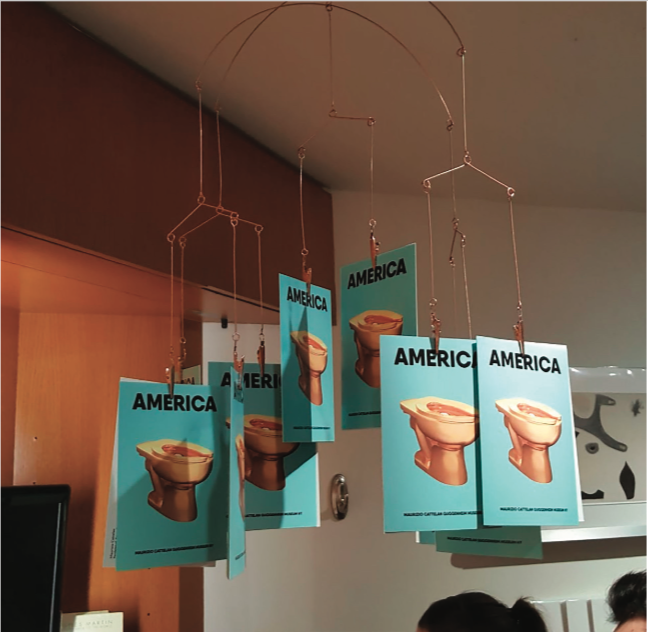

In Motel of the Mysteries, illustrator David Macaulay spoofed future archaeologist Howard Carson’s misinterpretation of the hallowed “Inner Chamber” of Tomb 26, with its Sacred Collar and “most holy of relics,” the Sacred Urn [4]. The title of Julie Horan’s The Porcelain God: A Social History of the Toilet highlights the revered nature of the place, even in jest [5]. That this most profane area is also considered sacred illustrates its importance as well as its ambiguity.

Humans universally share only a short list of primal biological necessities. Regardless of age and any other distinction, everyone must sleep, eat and eliminate waste. People defecate and urinate, answering “the call of nature.” Through these acts, our kinship with the rest of the animal world becomes real. Enter culture, defining how, when and where elimination should be carried out. In these private moments, culture slips to the background for everyone, as our physical nature is revealed. Bathrooms illustrate liminality, betweenness where the cultural normal is suspended, like no other place.

Naming Spaces

American awkwardness with that intimate, yet profoundly human, area is reflected in its variety of names. In the U.S., it is the “bathroom” or “restroom,” where neither bath nor rest is usually the main goal of the visit. But it is also the ladies’, women’s, boys’, gents’ or men’s room, the powder room, the little boys’ room, the little girls’ room or the potty (phrases used even by adults), the oval office, the john, the crapper, the shitter, the can, the head, the facilities, the necessary or comfort room, the porcelain throne or the inner sanctum; in particular locations, these paired rooms may have playful names such as Bucks and Does in an Adirondack restaurant or Buoys and Gulls at a coastal fish house. In private homes, a euphemistic name, “the library,” calls attention to the space as refuge, and as a space for reading brief selections from a publishing niche’s books written specifically for the room. Once upon a time, this place was an ungendered “outhouse”; surviving examples of these “biffies” may be the subject of tours and auctions, or even romanticized in poetry [6]. What it is not in the U.S. is the “toilet.”

In Britain, it is the W.C., the loo, bog, privy or the toilet, and many other names. At London’s British Museum, the facilities are “toilets,” but at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, they are “restrooms.” Indeed, one flies from Heathrow Airport in England where large signs point to “toilets” to JFK International airport in New York where the signs direct those in need to “restrooms.” On a plane, that important cramped space becomes the “lavatory,” a compromise intermediary.

“Toilet” is a problematic word, too explicit for many Americans except when it refers to that essential intimate paper of the room. In terminology long used in Europe, “eau de toilette,” or “toilet water,” referring to a fragrance applied to the face or skin, provokes only confusion or adolescent smirks in the U.S., where “cologne” or “light perfume” is preferred. “Toiletries,” a word dating from 1927, refers to the assorted cosmetics and aids to grooming used in the bathroom. When plans fall apart, they are said to be “in the toilet.” Cursing may be referred to as having a “potty mouth,” never as a “toilet mouth.”

The term “toilet paper” is used regularly when referring to this especially important bathroom item, yet American’s are reluctant to identify the room where it is used as the “toilet.” Toilet paper, first referred to in China in the sixth century, is so important it is the subject of at least two humorous books published in the same year, Bum Fodder: An Absorbing History of Toilet Paper [7] and Wiped: The Curious History of Toilet Paper [8] and an earlier book on business using toilet paper and associated terms as metaphors, The Toilet Paper Entrepreneur: The Tell-It-Like-Is Guide to Cleaning Up in Business, Even if You’re at the End of Your Roll [9]. That humor is the vehicle for this essential element merits interpretation as well.

Toilet paper is not only a $7.7-billion business in the U.S. in 2017 [10], it comes in myriad variations, used as a status mark in hotel rooms when it is folded and crimped, as art form in artists’ magazines and even as origami. Toilet paper distinguishes the rich world from the poor world, and in some American households, it differentiates social classes. Yet, as Morna Gregory and Sian James, authors of Toilets of the World, put it, “Unlike the rest of the world, North Americans generally avoid using the word ‘toilet’ whenever possible.” [11]

The private bathroom is an important center for serious matters. It is the only interior room where the door is usually closed and sometimes locked to insure privacy. In addition to eliminations, it is the staging area where both women and men recover from the disarray of a night’s sleep, cleanse themselves, perform oral ablutions of an importance anticipated by Horace Miner and don or adjust their daily public masks and costumes. It is a place where large mirrors and bright lighting are considered essential, a space where one gets ready for the rest of the world.

Public facilities located in businesses are formally identified as “restrooms,” yet in today’s debates, they have been given the more personal label, “bathrooms.” My ex-father-in-law, a socially liberal but somatically conservative minister from Georgia, always called my home’s bathroom a “restroom,” creating impersonal distance reflecting his own awkwardness with normal bodily processes. Although rather extreme, he is not alone in his discomfort with the space. Many Americans are much more at ease being entertained with bloodbaths, explosions and media violence than with seeing or discussing nudity, sexuality or bodily functions, let alone relaxing rigid standards of bathroom use.

The current politicized bathroom situation echoes simpler gendered tensions in the late 60s and early 70s when long-haired males disturbed conservative notions that long hair belonged only on females; then, females and males alike would line up to use the same facilities on university campuses, defying the very conventions being challenged today.

Public bathroom use has rarely been an equal-opportunity experience. Women often wait tolerantly in line for relief at concerts, ballparks, restaurants and plays while men breeze in and out of their designated space. With Broadway theater audiences now about two-thirds women, the pressures for “potty parity” during 15-minute intermissions are forcing owners to provide more commodious accommodations [12]. On occasions when justifiable impatience prompts women to abandon their line for an empty men’s room, there have been no newsworthy protests. The symbolic power, not to mention convenience, of binary facility equity inspired former New York Times columnist Anna Quindlen to invoke Virginia Woolf in her essay “Public & Private; A (Rest) Room of One’s Own.” [13]

Temporary, single-use cubicles are known by euphemisms such a Port-A-John, Honey Bucket, Porta-Potty, Rent-A-Can, Jimmy’s Johnnys, Don’s Johns or Larry’s Latrines (“It’s our business to handle your business”), are often called portable restrooms or bathrooms, and are sometimes listed as “portable toilets.” These remain one of the most awkward, unaesthetic places, but there is no ambiguity about their function. Here, female, male, gay, straight, transgender, young and old avail themselves to meet pressing needs. Nor do these democratic facilities provoke social outrage when used by anyone.

Accompanying this social description and sacred mystery has been a strict separation of public facilities as constructions of the genders their labels proclaim. Today, “the presence of the two distinct spaces is cited as proof that the difference they identify is sacrosanct, when in fact the twin rooms are, essentially, architecturally codified ideology, . . . supplying form to the fictions by which we live.” [14] Most of us rarely consider the extent to which design reinforces cultural constructions. Until President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, bathrooms (and water fountains) were the most conspicuous markers of racial segregation in the U.S. Now, gender issues are the center of public bathroom tensions. But a cultural perspective goes deeper than “mere” gender.

Fear Factors

Anxieties, both real and imagined, abound in the liminal zone of the bathroom. It is a place separate from the normal world, a place where activities go on that are awkward, unwelcome, not allowed or even illegal outside that space. For females on social outings especially, it is an important location to shore up one’s gender construction, or perhaps a protected social place to talk with friends about those not present. If male and out informally with other males, one should go alone to quickly perform one’s “business” without eye contact or social interaction for fear of being taken as less than “straight.” Male facilities reinforce homophobia.

It is also the room where hundreds of thousands and possibly as many as 17 million Americans, 7% of the U.S. population by one estimate, more men than women, experience paruresis, a social anxiety euphemistically called “shy bladder syndrome,” fear of someone knowing or hearing that you are urinating [15]. One uses the space, but exactly what one does inside is best kept within those walls.

Bathrooms are more dangerous than many realize, but not for reasons of the recent uproar. In a large, nationally representative sample survey by the Centers for Disease Control, some 235,000 people over the age of 15 went to the ER because of injuries suffered in the bathroom. Many of these were due to bathing and showering, but some 14 percent happened while using the toilet. Almost 33,000 toilet-related injuries sent people to the ER in 2008 [16]. With the aging U.S. population, these numbers are probably higher today. Clearly, bathroom use deserves caution.

The bathroom has long been a site of transgressions. Bullies give “swirlies”; underage boys and girls break school rules by smoking. Same-sex encounters in restrooms have brought down more than one male politician (yet no female politicians). On airplanes, the lavatory is where one joins the “mile-high club” by having sex in flight [17]. The most common, often contentious, bathroom misdemeanor, leaving the seat of the sacred urn down instead of raised when urinating, will be familiar to every American male living with someone who urinates while seated.

As if looking into a morning mirror weren’t scary enough, thanks to the magic of special effects, bathroom mirrors enhance edgy entertainment, often outright fright, in ways Sir James Frazer of The Golden Bough fame a century ago would find consistent with examples of the power of reflections over time and across cultures. When an actor in a movie or TV series stands before a bathroom mirror we are primed to expect drama, whether it is a melting or aging face, a demonic transformation, a reflection of someone long dead or a murderous threat in the background. Cultural storytellers use bathroom mirrors to amplify fear in the liminal zone.

Bathrooms join dark alleyways and cemeteries — but are more personal than either — evoking fear and dramatic tension in popular entertainment. Janet Leigh’s terrifying shower murder in Hitchcock’s 1960 Psycho lives on as “the greatest film scene ever shot” and “one of the best known in all of cinema.” [18] Ryan Lamble identifies “17 Moments of Movie Terror in the Bathroom,” a place where “we are at our most vulnerable,” including Psycho, but also The Shining, Poltergeist, Nightmare on Elm Street, Fatal Attraction, The Conversation and Jurassic Park, among others [19]. Murders, shootings, beatings, confessions, hand-offs of illegal drugs, secret codes, microchips and sex are legion in our entertainment bathrooms. Screenwriters recognize this space as an especially important setting. (Keep this in mind the next time you’re watching Netflix, and you’ll see what I mean.)

Before transgender matters and binary gender issues, public bathroom designations functioned to sustain racist divisions. The recent movie Hidden Figures tells the story of preintegration days at NASA/Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, where brilliant black female mathematicians worked separately, and of course had their own bathroom located inconveniently in a distant building. A pivotal moment in the movie occurs when project leader Al Harrison (played by Kevin Costner) realizes this and bashes down the “Colored Ladies Room” sign asserting, “Here at NASA, we all pee the same color!” A little later when African American Dorothy Vaughan (played by Octavia Spencer) is in the newly integrated women’s room, she has a passionate encounter with her hostile supervisor Vivian Mitchell (played by Kirsten Dunst), who treats her humanely for the first time [20].

Today, transgendered people, not culturally constructed races, are often the victims of binary bathroom architecture and accumulated bathroom anxieties, blindly exploited by politicians because they threaten familiar divisions. Irrational fear prompts extreme reactions, illustrated by a woman I heard on conservative AM talk radio responding to bathroom nondiscrimination pressures, “Those federal lawmakers want to take our children away from us,” she shouted.

The broader issue matters to everyone, however. Below surface political conflicts and controversy over gender spectrums, we all are affected by the deeper meanings of our bathrooms. Recognizing this, we would do ourselves a favor to consider the fuller cultural picture.

When you add up all the cultural issues and fear factors unmentioned in today’s bathroom brouhaha, it is little wonder that feelings run so strong. On the other hand, in the larger national picture, there has been widespread acceptance and support for changing attitudes about both gender and bathrooms. That is the biggest relief in this bathroom story.

~~~

Notes

1. Joellen Kralik, “‘Bathroom Bill’ Legislative Tracking,” National Conference of State Legislatures, February 2, 2017, http://www.ncsl.org/research/education/-bathroom-bill-legislative-tracking/635951130.aspx; Joellen Kralik, “Bathroom Bills on Trial,” State Legislatures, January 2017, 24–26, http://www.ncsl.org/Portals/1/Documents/magazine/articles/2017/SL_0117-BathroomBills.pdf; Wade Goodwyn, “‘Bathroom Bill’ Fight Brewing in Texas,” NPR Morning Edition, January 2, 2017, http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/01/02/507910587/bathroom-bill-fight-brewing-in-texas.

2. M. Gabriela Torres, “Fear in the Bathroom,” Anthropology News 57, no. 1 (2016): 32.

3. Horace Miner, “Body Ritual Among the Nacirema,” American Anthropologist 58, no. 3 (1956): 503–507.

4. David Macaulay, Motel of the Mysteries (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1979).

5. Julie L. Horan, The Porcelain God: A Social History of the Toilet (Secaucus, NJ: Carol Publish- ing Group, 1997).

6. Maria Puente, “For Those Privy to Its Joys, the Outhouse Is an Icon,” USA Today, April 1, 2000.

7. Richard Smyth, Bum Fodder: An Absorbing History of Toilet Paper (London: Souvenir Press, 2013).

8. Ronald H. Blumer, Wiped: The Curious History of Toilet Paper (New York: Middlemarch Media Press, 2013).

9. Mike Michalowicz, The Toilet Paper Entrepreneur: The Tell-It-Like-It-Is Guide to Cleaning up in Business, Even if You Are at the End of Your Roll (Boonton, NJ: Obsidian Launch, 2008).

10. Statista, “Sales of the Leading 10 Toilet Tissue Brands of the United States in 2017 (in million U.S. Dollars),” Statista, The Statistics Portal, https://www.statista.com/statistics/188710/top-toilet-tissue-brands-in-the-united-states/.

11. Morna E. Gregory and Sian James, Toilets of the World (London: Merrell, 2006).

12. Michael Paulson, “Broadway’s Bathroom Problem: Have to Go? Hurry Up, or Hold It,” New York Times, February 7, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/07/theater/broadways-bathroom-problem-have-to-go-hurry-up-or-hold-it.html.

13. Anna Quindlen, “Public & Private: A (Rest) Room of One’s Own,” New York Times, November 11, 1992, http://www.nytimes.com/1992/11/11/opinion/public-private-a-rest-room-of-one-s-own.html.

14. Michael Rock, “The Accidental Power of Design: Signs of the Times,” New York Times, September 15, 2016 https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/15/t-magazine/design/bathroom-debate-accidental-power-of-design.html.

15. Bryan Curtis, “Choking at the Bowl,” Slate, May 13, 2002, http://www.slate.com/articles/sports/sports_nut/2002/05/choking_at_the_bowl. html; S. Soifer, G. Nicaise, M. Chancellor, and D. Gordon, “Paruresis or Shy Bladder Syndrome: An Unknown Urologic Malady?” Urologic Nursing Journal 29, no. 2 (2009): 87–93, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19507406.

16. Nicholas Bakalar, “Watch Your Step While Washing Up,” New York Times, August 15, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/16/health/research/16stats.html; Judy A. Stevens and Tadesse Haileyesus, “Nonfatal Bathroom Injuries Among Persons ≥ 15 Years—United States, 2008,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 60, no. 22 (2011): 729–733, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6022a1.htm.

17. Mark Gerchick, “A Brief History of the Mile High Club,” The Atlantic, January–February 2014: 48–49, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/01/a-brief-history-of-the-mile-high-club/355733/.

18. Philip French, “The Greatest Film Scenes Ever Shot,” The Guardian, March 13, 2010, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2010/mar/14/greatest-movie-scenes-psycho.

19. Ryan Lamble, “17 Moments of Movie Terror in the Bathroom,” Den of Geek Blog, March 3, 2017, http://www.denofgeek.com/us/movies/movies/243458/17-moments-of-movie-terror-in-the-bathroom.

20. Anna Silman, “Hidden Figures Shows How a Bathroom Break Can Change History,” The Cut, January 6, 2017, https://www.thecut.com/2017/01/hidden-figures-shows-how-a-bathroom-break-can-change-history.html.

~~~

Robert Myers is professor of anthropology and public health at Alfred University in Alfred, New York, where he focuses on American cultural themes, especially those of violence, health, fun, and the impacts of social media. He spent two years in Nigeria on a Fulbright Lectureship. His essay “Trigger Happy with Gunspeak” appeared in Anthropology News November 7, 2016, “The Making of a Wrinkle Convert” was in SAPIENS, February 28, 2017, and “The Great American Cultural Eclipse” was in Anthropology Now online, November 20, 2017.