The past year has seen violent protests at most South African universities, where students have pursued the dual goals of free education and a decolonization of education. Severe dissatisfaction with everything from tuition fees, housing schemes, languages of instruction and symbolic tributes to colonial stalwarts have coalesced to produce a tense environment of conflicts and riots reminiscent of the world-famous student protests that were part of the struggle against apartheid back in the 1960s and 1970s. This has led some observers to liken current developments to the year 1976, when almost 200 black high school students in Soweto were massacred for demonstrating against a decree that forced all black schools to use Afrikaans or English as languages of instruction. In the resulting nationwide protests, as many as 600 students were killed in South Africa.

Content-wise, the issues that lead students to engage in protest activities today are actually quite similar to the causes their predecessors fought for so bitterly a half century ago. The historical context is obviously very different, of course, as are the style and organization of the protests. Yet, while South Africa has been governed by the African National Congress (ANC) since 1994, and one would be hard-pressed to regard the protesting students as antiapartheid freedom fighters as such, the legacy of the apartheid infrastructure abounds in issues at the fore in 2015– 2016.

Drawing on my experience living and working in South Africa from 2001 to 2003, and conducting one year of ethnographic fieldwork from 2006 to 2007 combined with intermittent fieldwork trips in 2011 and 2016, I would like to discuss three important changes in what has occurred during the past year’s protests at South African universities. First, violent struggle protests that were formerly associated with the institutional life of historically black institutions are becoming common in historically white institutions as well. Second, social media have emerged as important vehicles for mobilizing support, both inside and beyond university environments. And third, the #RhodesMustFall protest modality has taken student politics far beyond the Student Representative Council (SRC) structures, which are arguably seen to be too closely aligned with the governing African National Congress (ANC) and its established youth organizations to strike a chord with student masses looking for change.

Taking my cue from renewed tensions in the South African higher education landscape, I would like to explore the extent to which today’s student protests can be taken as an expression of the overall status of post-apartheid South African society. I do so by asking what is at stake for the protesting students, and by surveying whom they are trying to hold accountable for the shortfalls they experience.

![Figure 2. Statue. Photo by Danie van der Merwe. OpenStreetMap - Google Earth -33.957819; 18.461586 [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/2.0) or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](http://anthronow.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/oxlund-1.png)

#RhodesMustFall: Social Media and Symbolism as a Vehicle for Student Mobilization

The new form of student protest began by way of social media activism with the launch of a protest movement at the University of Cape Town (UCT). In March 2015, this campaign used a Facebook group called Rhodes Must Fall and the hash tag #RhodesMustFall on Twitter to argue that a statue of Cecil John Rhodes should be removed from campus. A colonialist mining magnate and politician, Rhodes was a zealous British imperialist who used his significant financial power as head of De Beers diamond group and his political influence as Prime Minster of the Cape Colony (1890–1896) to pursue an expansion of the British territory by founding Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe and Zambia) and by working toward the realization of his vision of a Cape to Cairo railway. Rhodes also set up the Rhodes Scholarship scheme, which for more than a century has supported students from English-speaking nations and territories plus Germany to pursue education at the University of Oxford, where Rhodes himself had studied. In South Africa, the Rhodes Memorial monument is set on the slopes of Devil’s Peak in Cape Town on land Rhodes once owned and out of which he donated large tracts to the University of Cape Town. This is why the main campus is situated where it is and one of the reasons a bronze statue of Rhodes was emplaced on campus in 1934.

Rhodes is a highly controversial figure in South African history. Not only was he a firm believer in the supremacy of what he called the Anglo-Saxon race and a proponent of white appropriation of the land, he was also deeply implicated in the second Boer War, which made him a charged historical figure with black South Africans and with Afrikaaners, who had demanded that the Rhodes statue at the UCT campus be removed as early as the 1950s. In short, taking account of the many layers of colonial and imperial connotations carried by this single figure, it is not hard to discern why Capetonian students of color find that “the fall of ‘Rhodes’ is symbolic for the inevitable fall of white supremacy and privilege at our campus,” as the #RhodesMustFall movement described it on Facebook [1].

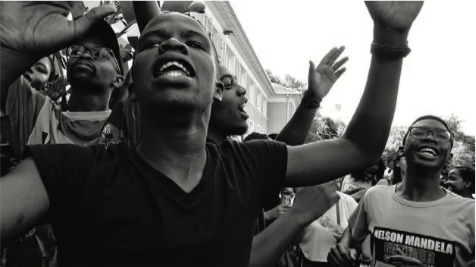

The March 12 launch of #RhodesMustFall was actually preceded by student activism on March 9, during which Chumani Maxwele smeared human feces on the Rhodes statue on campus and celebrated his deed in the special style of South African protest: chanting and swaying, known as “toyi-toyi’ing,” alongside a small group of student protesters. According to media reports, Maxwele got involved in a physical squabble with a security officer, for which he was later charged with assault. These initial events were followed by a student march to the UCT administrative offices at the Bremner building on March 20. The outcome was that the building was stormed by protesting students, who then took up occupancy for an extended period of time and renamed the structure “Azania House.” They did so in order to underscore the Africanist ideology of indigenous knowledge and racial identity the way it was originally promoted in the black consciousness movement inspired by thinkers such as Franz Fanon and Steve Biko.

On March 27, 2015, UCT’s senate voted to remove the Rhodes statue, and the university council swiftly endorsed this decision so that the statue could be removed on April 9. Arguably, Chumani Maxwele’s initial action created a momentum that saw the statue of Rhodes removed from campus within the short time span of just one month. Not only had Rhodes fallen, but a new protest modality of combined social media mobilization and on-the-ground action had erupted as the new normal on South African campuses since the tactics quickly spread to other universities in South Africa and even beyond. As far away as Oxford, California and Edinburgh, students of color found that #RhodesMustFall resonated with their own experiences of marginalization inside the academy and found it easy to identify with the need to do away with symbols of imperialism, colonialism and white supremacy. In January 2016, for example, students at Oxford voted in favor of removing their campus’s own statue of Rhodes, which was situated at Oriel College, where Rhodes had originally studied. But this decision was later overridden when infuriated donors threatened to withdraw support of more than £100-million.

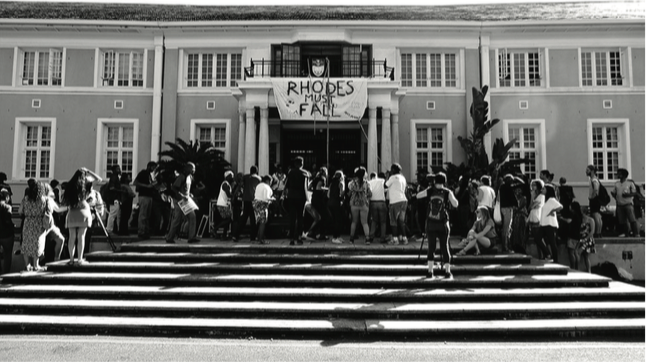

In South Africa it was perhaps unsurprising that students at Rhodes University in the Eastern Cape took inspiration from the #RhodesMustFall movement and demanded change at their own institution, beginning with a name change. On March 17, 2015, the Black Students Movement was launched, and after two months of protesting and complaining, the council at Rhodes University agreed to initiate a two-step plan to investigate the possibility of a new name. At Stellenbosch University, a campaign akin to the “…MustFall” initiatives called #OpenStellenbosch was launched to address that institution’s history of white exclusivity and dominance.

Inspired by the vibrant politics of symbolism sparked by #RhodesMustFall and a affliated campaigns, the controversial president of the left-wing opposition Economic Freedom Fighters party, Julius Malema, made a plea for all symbols of colonialism and apartheid to be removed nationwide. Less than a month after Maxwele smeared Rhodes in human feces, the statue of King George V at the University of KwaZulu-Natal had been similarly vandalized; a number of the Anglo-Boer War statues had been damaged in Uitenhage and Port Elizabeth; the statue of Paul Kruger in Pretoria had been painted green; and the statue of Louis Botha outside Parliament in Cape Town had been ravaged. Finally, in September 2015 the nose of the bronze bust of Cecil John Rhodes at the Rhodes Memorial was cut off, and derogatory graffiti was sprayed on the monument.

The developments that took off in Cape Town were formative in that the hash-tag prefix soon became emblematic of a new wave of student protests identifying socio-economic barriers and infrastructures that “must fall” to ensure equal opportunity in education. The successful #RhodesMustFall campaign had cleared the way for more things to topple. Of course, the mere removal of statuary could do very little to ensure the decolonization of education, and unsurprisingly the focus soon turned to the political realities of South Africa’s deep-seated structural and socio-economic inequalities. Next in line, therefore, were the #FeesMustFall and the #OutsourcingMustFall campaigns.

#FeesMustFall and #OutsourcingMustFall: Student and Worker Alliances in a Neoliberal Economy

When apartheid came to an end in 1994, the higher education sector was immediately deracialized and opened up so that universities would no longer be divided along the color line or designated as “white,” “black” or “colored.” The mid-1990s also witnessed a marked policy shift toward creating a competitive postsecondary market, which brought with it a less generous funding scheme, increased competition over students and staff and a growing demand for institutional responsibility. The historically black institutions were seen as being too weak, too small and too many, so from 1998 to 2005 a restructuring of the landscape of higher education took place that saw the number of universities reduced from 36 to 21 independent institutions (five new universities have opened since then). Arguably, the restructuring not only changed the size and shape of a number of universities but also created new meanings of institutional autonomy and accountability. This came with a new kind of managerialism and subscribed to the notion of a competitive market [2]. As I have argued elsewhere [3], the restructuring represented a shift from a focus on institutional redress to one of social redress, where individually supported students were expected to regulate the entire field of higher education through the exercise of their free choice. But in the South African social context, marred by the highest level of inequality in the world, it was almost absurd to operate with an inherent notion of the resource-poor student as a “free consumer” in a “higher education market.”

The fact is that even by African standards, South Africa spends very little on higher education, which means that universities as semi-independent institutions rely heavily on tuition fees as a source of income. In the 2012–2013 budget year, the South African government spent only 2.3 percent of its total budget on universities, which amounts to as little as 0.76 percent of the nation’s GDP. Over the past decade, government subsidy has decreased as a component of total university income from 49 to 40 percent, while the contribution from student fees has risen from 24 to 31 percent [4]. Now that the historically white institutions have enrolled many more students from resource-poor backgrounds, it is becoming increasingly difficult for these institutions to collect the tuition fees that in some cases make up almost half of their budgets.

In October 2015 this scenario became very clear when Wits University announced that it was planning to increase its tuition fees by 10.5 percent. The souring rand–dollar exchange rate was cited as a reason, along with increased salaries for academic staff and a general inflation rate of 6 percent. This led to a three-day student lock-down of the Wits campus in Johannesburg, which was succeeded by the national campaign #FeesMustFall when other universities announced similar tuition hikes in the double digits for the year 2016.

Although the campaign started out as a reaction to increased fees, it quickly merged with another agenda, namely protests against the outsourcing of many campus services to private contractors who offer meager salaries to staff such as cleaners and security officers. This pay scale stands in stark contrast to the salaries paid to higher echelons of university managers. For example, according to an October 2015 report in BusinessTech, vice chancellors are paid in the range of 2- to 4-million rand, the equivalent of $130.000 to $260.000 U.S [5]. Joining forces with the low-earning and outsourced categories of staff to demand both decent salaries and direct employment for service workers, students launched a campaign under the hash tag #OutsourcingMustFall in addition to the #FeesMustFall campaign. Basically, this meant that everything from symbols of colonialism to fees, wages of service staff and managers, outsourcing, declining government funding for higher education and a general lack of postapartheid social transformation and racial equality had come under review by the #…MustFall movement.

From October 14 to 17, 2015, events escalated at Wits University in Johannesburg, where the management agreed to hold negotiations with student groups to reexamine the announced tuition hikes. On October 19, however, students at University of Cape Town, Rhodes University and University of Pretoria started barricading vehicle access to their campuses. October 20 saw students at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Fort Hare University and Stellenbosch join the protests, while the students at Wits rejected a compromise 6 percent fee increase put forward by management. On October 21, students at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University in Port Elizabeth tried to block campus and ended up clashing with police, who used gas and rubber bullets to force control of the situation. Meanwhile, in Cape Town, 5,000 protesters marched on the South African Parliament, where a meeting was in session that was attended by both President Jacob Zuma and Minister of Higher Education Blade Nzimande. The latter unsuccessfully tried to address the crowds, while the former left Parliament through a side entrance. In the end, riot police came to the scene and dispersed the protesters using violent means such as electroshock weapons, gas, stun grenades and shields. The police were subsequently criticized for their heavy-handed approach since the protests had by and large been peaceful. Furthermore, 29 protesters were arrested under the National Key Points Act, which is an infamous piece of apartheid legislation from 1980 designed for the protection of sites of strategic national importance against sabotage.

The following day, students at University of Johannesburg had a run-in with university security personnel; students at Fort Hare damaged university property and lit bonfires; protesters gathered at the central magistrate court in Cape Town where the 29 arrested students were to appear; and students at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University blocked campus following unsuccessful negotiations with management there.

The next day, October 23, the South African student revolt reached the United Kingdom, where 200 protesters gathered outside South Africa House in Trafalgar Square, London. Meanwhile, in South Africa, President Zuma met with vice-chancellors and student representatives at his office complex in the Union Buildings in Pretoria to identify a way forward. Outside the Union Buildings, protesting students were lining up in large numbers, and some set fire to a portable toilet and broke down a fence. The police response was similar to the one adopted in Cape Town two days before — gas, stun grenades and rubber bullets became part of the action once again. Eventually, President Zuma announced from the safety of his office that there would be no increase in fees in 2016. Upset by the fact that the president did not address the crowd of protesters directly, a few students tried to storm the Union Buildings but were unsuccessful. Nevertheless, the #…MustFall movement had collected a new and unprecedented victory within a very short time span. Only 11 days after Wits University had announced its increase in tuition fees, nation- wide protests had insured that there would be no increases in fees for 2016 across the board at South African universities.

Although this is a truly remarkable achievement, it does fall short of “free higher education” as it was envisaged by the movement. Fees have at least held steady temporarily, but they have not fallen at all. Thus the scene of higher education in South Africa was destined to see more action from the #…MustFall movement during the time of registration in January and February 2016, when several universities eventually had to abandon onsite registration or temporarily shut down their campuses.

#Shackville and #AfrikaansMustFall: Questions of Housing and Language of Instruction

Among the most dramatic and significant events in the history of apartheid was the Sharpeville massacre that took place on March 21, 1960, when 69 unarmed protesters were killed and 180 injured by the South African police for demonstrating against the pass laws that required people of color to carry passbooks. Although South Africa was condemned by the international community for this event, the National Party government of the time proceeded to clamp down on the nationwide strikes and protests that followed in the wake of the massacre. This led to a total of 18,000 detentions of black activists that year. Since the onset of democracy, March 21 has been celebrated as a national holiday in commemoration of the massacre and in honor of human rights. Suffice it to say that Sharpeville is one of the most charged place names in South African history.

On February 15 of this year, #RhodesMustFall activists erected a shack at the steps to where the Cecil Rhodes statue had stood on the University of Cape Town campus prior to the events of early 2015. They called it #Shackville, an overt intertextual reference to the Sharpeville massacre. Aiming to draw attention to what they dubbed the “UCT housing crisis,” student activists put up the shack to highlight that black students experience systematic difficulties in finding accommodations. White international students are supposedly offered expedited access to accommodation, while white, privileged South African students are not asked to look for accommodation outside the residence system. In a statement, the activists wrote: “Shackville is a representation of Black dispossession, of those who have been removed from land and dignity by settler colonialism, forced to live in squalor.” The university management responded that if there was a housing crisis, it was related to the fact that 700 beds were not free due to deferred exams. Over- all, however, the university has resources to offer only about 6,700 beds, while the total number of students is approximately 27,000. Management requested that the shack be moved 20 meters because it interfered with traffic, but this drew a violent response. In the few days following the erection of Shackville, activists petrol-bombed the vice- chancellor’s office, threw human feces at students who were writing exams, burned down four vehicles and vandalized and set alight pieces of art that they considered to be colonial.

During those same days, things turned hectic at the University of Pretoria, which had to shut down its operations out of security concerns. Here black student organizations used #AfrikaansMustFall and #UPRising to demand that Afrikaans be scrapped entirely and as a prerequisite for academic employment at this university, which has historically had Afrikaans as its lingua franca. White Afrikaans student organizations, on their side, labeled the right to be instructed in their mother tongue as a human right in their defense of Afrikaans. This came to be known under the hash tag #AfrikaansSalBly (Afrikaans Will Stay), and it created a tense and insecure atmosphere in Pretoria. On February 22 the university management advised the public that henceforth English would become the sole medium of instruction, with Afrikaans and Northern Sotho as secondary languages only. Although this was a historic and groundbreaking development, in terms of public attention it was almost overwhelmed by news of violent clashes happening elsewhere.

On the eve of February 22, the University of the Free State became a public theater for the display of racial violence when a rugby match was disrupted by an #OutsourcingMustFall demonstration. The otherwise peaceful black protesters went onto the rugby field, where several of them were attacked and beaten up by white rugby players and spectators. Fighting ensued in the student residences, while video and photo coverage immediately went viral and became a testimony to the continued racial tensions at this particular institution, which in 2008 became renowned for an incident (and subsequent court case) where four white students had forced four black staff members to eat urine-soaked food as an act of humiliation. On February 24, in another corner of South Africa, protests at the Mahikeng campus of North-West University reached a peak over the inauguration of a new Student Representative Council deemed not to have been democratically elected. A science building and a residence were incinerated.

Protests continued in late March and early April. The first waves resulted in arrests of activist students and court interdictions against them, prompting even more protesting. One of the more curious developments seen over the course of March and April 2016 was the countercampaign launched by feminists and transgender students, who claim that the #…MustFall movement has hitherto been patriarchal and misogynist. They have therefore started mobilizing under the hash tag #PatriarchyMustFall, and during the student riot at Wits University on April 5, where a lecture theater was set alight, feminist, queer and transgender students launched counter-campaigns in the middle of the action.

One outcome of this development is that #RhodesMustFall activist Chumani Maxwele, who smeared feces on the Rhodes statue, has ironically been hit by a so-called social media shit storm for a violent squabble that he had with a female #PatriarchyMustFall student during that event. People weary of all the #…MustFall initiatives have now launched an #EverythingMustFall hash tag, where some keep track of the latest news in all sectors, while others laconically comment on the destructive undercurrent in the #…MustFall rhetoric and campaign modality. The question is, of course, where does all this lead?

#EverythingMustFall: “Toyi-toyiing” for New Politics

“Toyi-toyiing” as an embodied form of resistance offers a time-hallowed modality for students to voice their dissatisfaction at historically black institutions [6]. Dressed up in new social media attire under the hash tag #…MustFall, this still seems to be the case in 2015 and 2016. It also resonates with the fact that other sectors of South African society have witnessed similar dynamics. The year 2012 became notable for mining strikes that peaked with the dreadful Marikana massacre in which 44 mineworkers were shot dead by police, while service delivery protests have been so rampant over the past five years that South Africa has emerged as “the protest capital of the world,” according to some [7]. The odd thing is that this level of dissatisfaction has not come through in electoral politics, where the ANC has continued to garner more than 60 percent of the votes in most elections. Since the onset of democracy, ANC as the broad-based struggle movement has offered racial reconciliation without forced redistribution of land and goods. The party has been able to keep the story going that South Africa is the Rainbow Nation of God that has succeeded in firmly relegating racial politics to the ugly past, while at the same time rehabilitating the nation to international glory as an outstanding member of the family of nations. By popular measure, this was achieved by the hosting of the FIFA Soccer World Cup in 2010, but by political standards, South Af- rica has been playing its part as a regional superpower at the United Nations and the African Union ever since 1994.

Myriad descriptions offered in this short piece are testimony to the fact that the fairy tale of a peaceful transition from apartheid to postapartheid South Africa no longer holds sway. Racial rhetoric and violent struggle are becoming the order of the day, and while the South African intelligentsia and political moderates publicly decry the reality that democratic dialogue seems to be collapsing, only a few address the problem that underserved and marginalized groups are never heard when they do not engage in violent protests. In terms of higher education, it is problematic that the activist students are trying to make the independent institutions accountable for issues that can only be solved at a much higher level of political decision-making. Burning down a lecture hall will not yield free education, but as demonstrated, it might prevent an increase in the tuition fees that one has to pay in the short run. The overall question seems to be: when will the South African electorate decide to hold the ANC accountable for the lack of social redress in South African society? Judging from the launch in December 2015 of the hash tag #ZumaMustFall and the reduced support for the ANC in the local elections held August 3, 2016, that moment is not necessarily so far away.

Notes

1. https://mobile.facebook.com/RhodesMust Fall/about?expand_all=1. Accessed on June 1, 2016.

2. Jonathan D. Jansen, “Changes and Continuities in South Africa’s Higher Education System, 1994 to 2004,” in Changing Class: Education and Social Change in Post-Apartheid South Africa, ed. L. Chisholm (Pretoria: HSRC Press, 2004), 293– 314.

3. Bjarke Oxlund, “Responding to University Reform in South Africa: Student Activism at the University of Limpopo.” Social Anthropology/Anthropologie Sociale 18, no. 1 (2010): 30–42.

4. News24Wire, “What You Need to Know About University Fees in South Africa,” BusinessTech, October 23, 2015, http://businesstech. co.za/news/general/102010/what-you-need-to- know-about-university-fees-in-south-africa/.

5. Staff writer, “What Vice-Chancellors at South Africa’s Top Universities Earn,” BusinessTech, October 20, 2015, http://businesstech.co. za/news/general/101654/what-vice-chancellors- at-south-africas-top-universities-earn/.

6. Bjarke Oxlund, “Responding to University Reform in South Africa: Student Activism at the University of Limpopo,” Social Anthropology/Anthropologie Sociale 18, no. 1 (2010), 30–42.

7. Jeremy Seekings and Nicoli Nattrass, Policy, Politics and Poverty in South Africa. Development Pathways to Poverty Reduction (Hampshire: Pal- grave Macmillan, 2015).

Suggestions for Further Reading

Cloete, Nico, Pundy Pillay, Saleem Badat, and Teboho Moja. South African Higher Education. Oxford: James Currey, 2004.

Njabulo S. Ndebele. 2007. “Higher Education and a New World Order.” In Fine Lines from the Box — Further Thoughts About Our Country, 190–199. Houghton: Umuzi, 2007.

Oxlund, Bjarke. “‘Burying the ANC’: Post-Apartheid Ambiguities at the University of Limpopo, South Africa.” Social Analysis 54, no. 3 (2010): 47–63.

Oxlund, Bjarke. “Fighting to the Last Drop of Our Blood: Invocations of Radical Struggle Masculinity Among Black Student Politicians in South Africa.” Nordic Journal for Masculinity Studies 2, no. 5 (2010): 132–150.

Robins, Steven L., ed. Limits to Liberation After Apartheid. Citizenship, Governance and Culture. Oxford: James Currey, 2005.

Bjarke Oxlund is associate professor of anthropology at the University of Copenhagen. For his doctoral dissertation — “Love in Limpopo: Becoming a Man in a South African University Campus,” University of Copenhagen, 2009 — he conducted a year of fieldwork in South Africa. Bjarke is the author of several articles on higher education in South Africa but is currently involved in a range of major research projects concerning health, aging and the use of medicines in Denmark.

One Response

A piece on new developments was just published in the Opinion section of the NYTimes on 10/30:

“My South African University Is on Fire”

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/31/opinion/my-south-african-university-is-on-fire.html?action=click&pgtype=Homepage&clickSource=story-heading&module=opinion-c-col-right-region®ion=opinion-c-col-right-region&WT.nav=opinion-c-col-right-region&_r=0