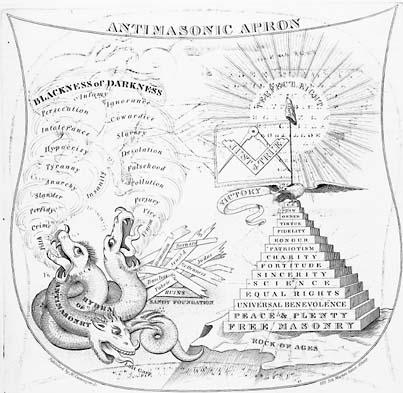

It is both disturbing and fascinating to follow the role of conspiracy theories in U.S. politics over the last decade and their apparent relationship to the Internet. One could claim that nothing has really changed, that mysterious and powerful cabals have always played a significant part in the U.S. political imagination. Consider the Anti-Masonic Party (1828-1838), which was founded in Upstate New York by Federalists to challenge the perceived influence of secret societies on settler life, or the Midwestern Populists, at the end of that century, who alleged that an international Jewish conspiracy was responsible for lowering farm prices.

Conspiracy theories about treacherous minority groups, political factions and foreigners are not exclusive to the U.S., of course. In Jordan and elsewhere in the Middle East, one of many anti-Zionist rumors holds that Pepsi actually stands for “Pay Every Penny to Save Israel,” a belief that has helped encourage boycotts of foreign products. Throughout Latin America a legend of children being abducted for organ harvesting spread moral panic at the end of the twentieth century, which ultimately led to an attack on an innocent tourist in a Guatemalan town in 1994.

In her new book, Real Enemies (2009), historian Kathryn S. Olmsted claims that this widespread tendency to project treacherous plots onto various cultural “others” began to change direction in the U.S. after WWI, when the role of the federal government expanded considerably. While the moral panics of the Red Scare and the McCarthy hearings are well documented, for most of the twentieth century people in the U.S. have been equally if not more captivated by secret government plots—the hidden assassins that assisted Lee Harvey Oswald from the grassy knoll, the Roswell landing that did happen, the Moon landing that did not—and, by all accounts, they find these theories more convincing than ever. A similar number of Americans—around 80%—believe that Kennedy’s assassination and the existence of extraterrestrial life have been covered up. To take the first example, according to a recent Gallup poll 34% believe that the CIA was responsible for Kennedy’s death, and 18% blame Lyndon Johnson. At the time of the assassination, only half of Americans suspected a conspiracy, but the percentage grew after the release of findings from the House Sub-committee on Assassinations (HSCA) in 1976 and Oliver Stone’s movie “JFK” in 1991.

If anything changed with the rise of post-modernism and the information society, it is the introduction of a suffix to brand conspiracies and related events. Since Nixon’s disgrace and resignation, it has become commonplace to label popular scandals and cover-ups with “-gate.” The addition of this signifier says nothing about the reality of an alleged crime, whether it actually took place, but only its reality as a particular kind of media event. True media events are, strictly speaking, “new news.” As Greg Urban argues in his book Metaculture (2001), news constitutes an important form of “culture about culture,” one which frames occurrences in a meaningful sequence as “stories.” Though media events are partly triggered by public interest, they are heavily shaped by how happenings around the world are presented as new and important within the non-stop telecommunication cycle. With the perpetual search for “new news” to sell, actual events quickly disappear into the background with each story that “breaks” and more and more attention goes to the process of metacultural production itself: the format of news presentation, the personalities of the pundits and anchors who present it, and the storylines that accompany competing brands of new news (e.g., “liberal vs. fair and balanced”). The “-gates” suffix indicates a particular way of presenting new news; such is the appeal of its narrative model. It is only appropriate that this is the lasting legacy of the Nixon administration’s very real cover up, which is linked in the public imagination with a growing paranoia about government power in general. Indeed, still today much is made of the missing 18 ½ minutes from the Watergate tapes, as if any of the actual revelations that became public are exceeded by the event’s symbolic import as the first “-gate.”

I would amend Olmsted’s claim only slightly and suggest that over the last decade the culture of political paranoia may have made another significant break with the past. As new “-gates” continue to develop and disappear in the twenty-four hour news cycle, those who believe in such cover-ups are now themselves suffixed into a type: 9-11 truth-ers, Obama birth-ers, Osama bin Laden death-ers, and so on. One could argue, though I know no one who has, that this may have originated from the use of the appellation “Holocaust deni-ers” (that ostracized and discredited group to whom other conspiracists are often compared, much to their chagrin). Regardless, this shift from marking events to marking persons is telling. For one thing, it reflects the relative ease with which like-minded people, of all political persuasions, can not only find and amass information and opinion, but also share it through a wide variety of media channels.

Any time a new type of subjectivity arises a new form of “making up people” is involved, as philosopher Ian Hacking puts it. Being an “-er” is distinctive, as a new way of being a person, because it involves sharing one, and only one, belief. Even anti-masons, populists and anti-communists had other agendas, but an “-er” need only possess a single conviction, one which spirals out into a predictable set of propositions: that there is some cover up of significant proportions and that government officials, experts and members of the media are complicit in spreading a lie. As Hacking argues, there tends to be a “looping effect” when new human kinds are introduced. Pundits may think they are dismissing conspiracy theorists when they give them a suffix, but they are also giving them a rallying cry (“no one believes us, look how we’ve been unfairly excluded…”) and, before long, a Wikipedia entry.

As is common with new human kinds, much is made of what makes them the “type of person” who could “believe something like that.” Less discussed is why many of us are not that “type of person.” After all, conspiracies do happen. Government officials do lie and conceal facts from the public on a regular basis, even if only about infidelities, campaign contributions, and relationships with special interest groups. They might not possess secrets about aliens and assassinations, but they must surely collude in various ways to misrepresent their actions to the public. Similarly, members of the media can and do selectively misrepresent events to suit the interests of corporate sponsors and their own ideological commitments. It is hardly surprising that Fox News Channel and its affiliates have reported very little on the phone-hacking scandal that engulfed its parent company, News Corp, this summer. Many are aware, similarly, that the “Clean Coal” lobby sponsored the presidential election debates on CNN in 2008, during which “clean coal” received a strong endorsement from all of the candidates. Finally, expert accounts may indeed be riddled with errors of judgment, shaped by personal and political ambitions, and so on. Scientists from the Climate Research Unit at the University of East Anglia, for example, may have actively sought to have the International Panel on Climate Change exclude views they disagreed with and include their own instead, and this may seem like a good conspiracy tale—it was certainly enough to give the episode a “gate” suffix during the extensive media coverage—but it is also something which can happen during normal academic peer review processes.

And yet, the reality of collusion in the corridors of power does not prove conspiracists correct or make them seem any more believable to the majority of us (at least for now). To paraphrase philosopher Slavoj Zizek (1999), even someone whose paranoid suspicion about their partner’s infidelities is proven correct is still pathologically jealous, because their beliefs are ultimately rooted in fantasy, not fact.

Why are many of us not conspiracist believers? Check back on Wed, August 17th for Prof. Joshua Reno's answer in Part 2 of this two part essay!

Joshua Reno is a lecturer at Goldsmiths College, University of London, in the Department of Anthropology. He received his PhD from the University of Michigan in 2008. He has articles on waste, techno-science, and environmental politics appearing in Cultural Anthropology, American Ethnologist and Science, Technology and Human Values in 2011 and a book co-edited with Catherine Alexander on recycling economies expected in 2012.