(COVID) Time Marches Grinds On

Robert Myers

When did it become July? Last month, I guess? A lot of flag waving and fireworks online, and no mail, so I think we had another 4th of July. Now it’s August. Oh wait! It’s September. It seemed like March only a couple of years, I mean weeks, ago. Which year is this?

A New Yorker cartoon from last week hit home: Man on couch covered in cobwebs says to woman standing at the open front door, “But I don’t remember what life is like out there.”

“Quarantine fatigue” is real, pervasive, and deep. And it’s largely about time, directly or indirectly.

The pandemic has upended my familiar world once structured by time. A sabbatical removed me from the usual classroom and committee obligations, setting me apart for a year already. Short trips to two of the most remote communities on earth—where during one visit there was no darkness and for the other there was no sunshine—pushed me further from time’s natural anchors. Political events cascaded during the year without relief. Then came the coronavirus pandemic with months-long self-imposed isolation, pushing senses of time and its routines into altogether new territory. The sabbatical luxury of time at my disposal became COVID-time.

The pandemic’s COVID-time forced greater awareness of this fundamental concept. Time is always present in myriad ways, consciously, metaphorically, without thought. In fact, there’s hardly an aspect of human lives which isn’t connected directly or indirectly with time.

Time’s Journey

Big story measures and metaphors for time have long been in play. Time began for many “In the beginning . . .” or with Archbishop Ussher’s Biblical creation story opening in 4004 BC, and became for others the earth-long geological time of James Hutton and Charles Lyell’s uniformitarianism, today’s Geological Time Scale and the “deep time” of John McPhee’s Basin and Range. Linear industrialized society raced from the 20th century into the 21st, surviving Y2K in the process. Today scientists segment time down to a micro-“particle” in motion on the NIST-F1 Cesium Fountain Atomic Clock at the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Boulder, Colorado. Time became digitized. Throughout this journey, time has shaped language, behavior and thoughts. Linear time is sub-divided, even as it is poetically conceived of as a river flowing, beyond human control. Many cultures think of cyclical time, or time which humans create, but those are other places, other customs, or Time’s Arrow, Time’s Cycle, as Stephen Jay Gould described it in 1987. Time has few rivals for the important roles it plays in human life. Now it’s COVID-time.

Dickensian time—‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times’—became a famous cliché serving sentiments well. By mid-2020, however, this famous literary beginning seems too binary, overly simple and incomplete. It doesn’t capture complex COVID-time.

Time out. Keep your eye on the clock. Pay attention: the 3-second rule, 60 seconds, 50 minutes, 8 hours, 24 hours, 40 hour work week, 168 hours in a week, 2 weeks’ vacation, 9 months gestation, 12 months, 365 days, leap year, 5-year plan, all familiar units of time. Once, a time clock ruled labor. Punch in to get paid for your time. No rush. Wrong. Hurry up. Get on with it. Can’t you move faster? The clock is running 24/7. I need that report inanewyorkminute. Time is relentless, but at least it flies when you’re having fun. Why would anyone want to kill it? Tick tock, tick tock. Time’s up. Time, gentlemen, please. See you later alligator; after a while crocodile. And echoes of Captain Hook’s nemesis: Tick tock morphed into TikTok.

Some version of the time-warp song and dance, jumping to the left and stepping to the right—whether from the ‘70s Rocky Horror or in daily life—feels inescapable.

Calling something timely, or a story timeless, elevates its standing. Other attitudes devalue the importance of time depth. At a cost, some ignore a fuzzy past Huck Finn-style, “I don’t take no stock in dead people.” Too many dismiss the past à la Henry Ford’s “history is bunk,” even as they scrapbook, visit cemeteries, compile family trees, or frequent antique shops. But to Ford, time was money. He had no free time; his time was valuable. He spent it, saved it and rarely wasted it.

Storytelling, whether pop, lit, movie or song, concerns time. Chaucer enshrined the truth that “time and tide wait for no man” in his prologue to The Miller’s Tale. That Connecticut Yankee visiting King Arthur was relieved to return to the nineteenth century. H.G. Wells, the “man who invented tomorrow,” took readers to the future in his Time Machine. Viewers crossed the Eighth Dimension with Peter Weller as Buckaroo Banzai, thanks to an “oscillation overthruster.” Marty McFly and Doc Brown went Back to the Future in a retrofitted DeLorean. Brendan Frasier’s Blast from the Past playing with 35 years of isolation, puts present months of confinement in perspective. Proust’s elegant journey down memory lane, In Search of Lost Time, pivoted on the scent of lime blossom tea and the taste of madeleines. With Ulysses, Joyce imagined “all of life in a day,” Bloomsday, June 16, 1904, in Dublin. Definitely a GOAT. Both the Rolling Stones and Freddy Mercury echoed Chaucer with their “Time Waits for No One” . . . “and it won’t wait for me.”

Analog time > Digital time > Streaming time > COVID-time > After Time

Those of us who grew up in a time when there were three television channels and barely 24-hour broadcasts might recall Buffalo Bob’s mantra, “Say kids, what time is it?” The response, “It’s Howdy Doody time!” echoes another era. Indeed, as many have noted, “the past is another country.”

Nostalgia re-sets time, rearranges memories, and selectively mis-remembers things past as the “good ol’ days.” “Make America Great Again” puts time to political ends, without perspective on change or awareness of re-using a MAGA Reagantime slogan. Retro recycling.

Rapid technological and cultural change accelerated a sense of time throughout the 20th century. Not only were time-management experts necessary to teach people how to more efficiently produce things, but also how to use time more wisely. Google “time management” and “use time wisely” for more on this. Schedules and lists shaped our lives then and now. Advice still abounds. “Give me ten minutes and I’ll change your life,” demands the self-help guru. Andy Warhol’s 1968 declaration, “In the future, everyone will be world famous for 15 minutes,” feels either short-sighted, ominous or on some mark, depending on one’s attitude, and the time of day.

What’s your rush? Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five” pleaded, “Won’t you stop and take a little time out with me?” “Slow down, you move too fast,” sang Simon and Garfunkel in 4/4 time, feelin’ groovy, early 1966 in an accelerating age. About 154-million adult Americans paused for all of three minutes on August 21, 2017, to view the Great American Eclipse live while another 61 million watched it electronically. It is little wonder that the fast modern pace has given rise to the slow food and slow living movements. Retro striving.

Many became ever busier as the home/office, leisure/work binaries blurred. Sociologist Arlie Hochschild’s The Time Bind: When Work Becomes Home and Home Becomes Work (2001) formally captured this late modern pre-COVID time dilemma. Parkinson’s adage, “work expands to fill the time available for it” was conveniently ignored. “Busy” became (and remains) a virtue easily signaled, as work itself has a sacred quality to Americans. Adam Gopnik’s brilliant story “Bumping into Mr. Ravioli: A theory of busyness, and its hero” captures the penetration into home life of busyness performed by a child in New York City.

“Busyness is our art form, our civic ritual, our way of being us,” Gopnik writes. Oh thanks, but gotta run, I’m soooo busy. Let’s do lunch next week. Maybe just coffee. We’ll talk soon. Call me. Sorry, I’m not available right now. Later. Leave a message.

Digital-Time

Analog time transitioned to digital time literally and symbolically on our wrists. This was a profound shift according to Jeremy Rifkin, who argues in Time Wars: The Primary Conflict in Human History (1989) that analog time keeps humans connected to the natural rhythms of the planet. Analog watches preferred by women Rifkin claims—when most people still wore watches—moor people in 12-hour cycles. He insists that digital watches disconnect us from everything except an isolated moment represented in simple numbers.

The digital era has played havoc with time for decades. Instantaneous internet, email, Wikipedia, and Google made pre-electronic life practically pre-historic. The pace changed, and a sense of time’s reality transformed. Real life became reel life, and then disc life. Rewind became reset.

By 1972 Memorex was asking “Is it live, or is it Memorex?” A “live” recording could be broadcast any time, passing itself off as really there, yet was only there (wherever “there” was) virtually. The “LIVE” label in the corner of news or concerts’ broadcasts already distorted our time relationship with events. How “live” is an event if it is not literally synchronous with the viewer? Death of persons or events was extinguished, or at least minimized, by recordings. Videotaped, or reincarnated, for your convenience, for time immemorial. Recorded. Replayed. Rebroadcast. On demand. “Live” for your viewing whenever. DVR, beginning in 1999, delivered control of “live” broadcasts into the hands of busy consumers. Within 10 years, a DVRer could record anything on TV, broadcasting it “live,” fast-forwarding through commercials. The illusion of virtual control over time rested in the hand of the couch jockey.

Work time changed substantially. Increasingly, some jobs allowed work from home, fogging the office-home divide. A “connected” person was available to the office, to a boss, a partner, family or friends 24/7, “in real time.” In June the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released its “American Time Use Survey” for 2019. According to surveys of leisure, Americans ages 15 years and over spent 5.19 hours in leisure activities daily, of which 2.81 hours were spent watching TV and .43 hours playing video games, vs. 0.31 hours spent thinking or relaxing and 0.27 hours reading. I suspect the viewing and playing categories are self-reported underestimates, and this data will certainly change for 2020.

Cell phones and social media have profoundly altered their users. (My phone reports, “Your usage this week is up 36%; you spent a daily average of 4 hours and 31 minutes on your phone, down 26% from last week.”). Many have become more isolated, imagining they are more connected and more in control of their lives. Comforting thoughts, but untrue. Michael Wesch’s entertaining “An Anthropological Introduction to YouTube” has been viewed more than 2,000,000 times; students initially scoff, treating it like ancient history, but then are drawn into his analysis. Consider that 300 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube each minute for easy access by hundreds of millions in a fractured global time orgy.

Phone life and social media effects are examined ad infinitum. Books and commentary become dated rapidly. Howard Gardner and Katie Davis described not U.S. youth in The App Generation (2014) but a global app world. There are new books, TED Talks, studies, articles, podcasts, blogposts and videos every day, plus a world of tweets, buzzfeeds and reddit threads. Every contemporary entertainment incorporates cell phone interruptions into the story. “Saved by the bell” has become “saved by the cell.”

Sorry, I’m too distracted by my phone to focus on this any longer. I have to enter today’s “Creative, Health, and Task activities” into my 168 app (“Balance your most precious asset, time”). Of course I can edit anything I enter. Is it going to rain tomorrow? Let’s see. At 11 am, there’s a 40 percent chance of light showers. How’d I sleep last night? Let me check. My sleep app says I had three hours and seven minutes of deep sleep in a total of six hours and 28 minutes of sleep. “Leaving for Rochester in 15 minutes” my phone announces.

Why’re you calling again? Don’t call. Text. Post on your Insta (or Finsta) so I’ll know what’s going on. What’s your favorite YouTube channel? Who do you follow? Loved your new TikTok. What’s trending on Twitter? Click. Swipe. Click. Scroll. Click. Swipe. Sorry, just seeing your email now.

Streaming-Time

Time entered new uses and influences with streaming technologies. Since 2007, Netflix has been streaming entertainment, disrupting fixed channels on TV. It has spawned myriad streaming services, from Hulu, Amazon Prime (which began as a free shipping service in 2006), Peacock, and Sling TV (and many more) to the new Disney+ on which one can watch a sanitized Hamilton with two of its three “fucks” removed. One “fuck” is OK; two “fucks” gets an automatic MPA R-rating. Corporations control the opportunity to watch thousands of shows by subscription whenever one pleases on virtually any topic, and more movies than anyone knew existed. Individuals make the choices and time commitments. Big Little Lies? Mrs. America? Night on Earth? Alexa, find Parasite. Fast-forward to the present.

COVID-Time: January to August 2020

In The God of Small Things, Arundhati Roy writes, “It was a time when the unthinkable became thinkable and the impossible really happened.” At first, this seemed a perfect line to describe the global pandemic, which as of September 2, has infected more than 26.2 million people (>6.2 million in the U.S.; >468,230 in New York State) and killed more than 866,622. It has brought the global economy to a crawl, nearly closed the global tourism sector, cost airlines tens of billions, closed schools and universities since March, pushed millions out of work and instilled fear and uncertainty in countries around the world. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation projects 224,576 COVID deaths in the U.S. by November 1. Most reports include only positive cases and deaths; when other categories are added, more is known, but far from enough. Since the spectrum of consequences from coronavirus infection is large and complex, anxieties about becoming infected remain abstract. Hopes about vaccines for COVID are centermost in discussions of the future.

If Roy’s line applied to a pandemic (which it doesn’t; it’s about family and kin), it would describe a global situation only for those who never studied public health, medical history or virology. Another Big One has been both thinkable and possible. In The Great Influenza, John Barry reports that a deadly pandemic has been expected since the 1918-19 pandemic killed an estimated 50 to 100-million worldwide and at least 675,000 in the United States in a matter of months, out of a total U.S. population of 105 million. The only question for public health people has been the time question, “When?”

Everything has been altered by the pandemic, especially how people use and think about time and space, our own and that of others. Chinese artist Ai Weiwei writes eloquently, “The understanding of time is lost”. Eventually, we will speak of pre-COVID and post-COVID life, rather than pre-911 and post-911 or pre-digital and post-digital existence. Someday instead of saying, “That decision really plagues me,” we’ll say, “That decision really covids me.” By then, most of the pre- and post- differences may be long forgotten.

COVID-time upends and intensifies everything. It feels both slower and faster, both less and more linear, both more and much less under one’s control than pre-COVID time.

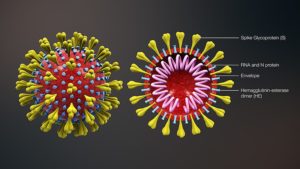

New events challenge metaphorical creativity. Naming the thing on the borderland between living and non-living is based on idealized images of a variable sub-microscopic (0.06 to 0.14 microns, 6-14 nanometers) RNA sphere with projections, somewhat like the corona of the sun, or a crown.

These colorized images make the virus “real” because otherwise it would remain unimaginable. The artificial yet aesthetically-engaging images bring the threat to “life.” It was the novel coronavirus, then 2019-nCoV, SARS-CoV-2, “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2” and finally COVID-19, Covid-19, or simply “the virus”. Manageable names, images and metaphors shape perceptions and actions. They provide more of a “handle” on the viral threat and ideally add traction to efforts to convince people that the threat is real.

People search for the most effective ways to describe this global tragedy. Graphs showing waves, surges, spikes or upticks seem to have straightforward staying power and are coupled with geometric emphasis on “flattening the curve” as numbers of cases “rage,” “erupt,” “sky-rocket” and “explode.” President Trump describes this as a “war” against a vicious, invisible invader from China, the Wuhan virus, China flu, Kung flu, or Chinese virus.

Other metaphors give the event dramatic “reality.” We’re in the zombie apocalypse, perhaps the second inning of a nine-inning baseball game, or not even mile five in a marathon. Tom Frieden, former Centers for Disease Control head, likened the situation for the health system to fighting with one hand tied behind your back and, recently, to a boxing match. “It’s like leaning into a left hook. You’re going to get hit hard.”

It’s not quite a perfect storm, but feels like a hurricane we watched approach for weeks. Now it’s swirling around the country, wreaking more damage than several Katrinas. Or perhaps hurricane-prone Florida is a “perfect storm”. In “hot spots,” coronavirus contagion has almost become a tornado. Winter is coming again; this may be August, but we’re in a blizzard. “We’re in a forest fire that may not slow down,” warns Dr. Michael Osterholm, epidemiologist and director of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. Close the window, corral this beast, build a wall against it. Our situation is like walking across a frozen lake; you’re far from the edge and you hear the ice cracking under your feet. “It’s like swimming for shore and not seeing shore,” said a physician in South Florida. Similes for high caseloads emerged. In hard-hit Tampa, one physician said it’s like “a bus accident a day, every day”. One meme explains the viral spread in craft terms: “You and 9 friends are crafting. One is using glitter. How many projects have glitter?” (Bunnie Magee, Facebook).

Quarantine, self-isolation, lock-down and shelter in place are the heart of COVID-time “mitigation.” The main goal of all efforts is to slow down the viral impacts, to buy time until a safe vaccine is approved. Months of isolation at home alter personal and professional habits. This new confined lifestyle has never been the norm for unincarcerated Americans and comes with costs. Prolonged togetherness can feel forced or fragile, even among loved companions. Far from an endless vacation for those still being paid, the quarantine challenges creativity and brings opportunities; virtual concerts; virtual travel; virtual, virtual, virtual. Those VR goggles for Christmas were incredibly timely! And there is lots and lots and lots of family time. How was that online class about birding? What’s your best score on Fortnight? Minecraft? League of Legends? Best time on the seterra.com UN nations’ flag quiz? (online.seterra.com).

Feeling overwhelmed, procrastination, even paralysis are normal reactions to stress and prolonged confinement. Staying busy has an upside, but for some, busyness is a bridge too far. Relentless daily news, social media warnings, and exhaustion from the un-expected duration of isolation wear one down. COVID-time amplifies a pre-existing American “culture of fear”. Germaphobes and agoraphobes are having a terrible time, but confide, “See, I told you so.”

Busyness didn’t disappear. It took different forms, requiring reorganization, rethinking and sometimes remotivation. Despite theoretically having an abundance of time, that time had to be repurposed for home or family tasks as well as job demands. It became a more complex busyness with a different set of faces and personalities on the work stage or always in the wings. COVID-time mashes Arlie Hochschild’s “work is home, home is work” together in challenging ways. Cut yourself some slack. “Allow yourself to be unproductive. At least for a little while,” encourages CEO Peter Bregman.

Parents reorganize homes for new work space and children’s play spaces, serving diverse ages and attention spans. How one spends time must be negotiated since space is being shared for long periods. Children get a pass for much longer online and screen time. Will schools open in the fall? We’re damned if they do and, some insist, damned if they don’t. Scheduling virtual play dates or outside contacts presents challenges. Every outing and each encounter must be carefully considered, if one leaves home at all. Will they deliver that to the house or require curbside pickup? Does Amazon carry those? Damn. I forgot to take out the trash. What about Grandma in the nursing home? Long-neglected house projects call out relentlessly. Pressure-treated lumber is in short supply, like toilet paper in early March.

What day is this? Already?

Everyone still must eat, which means more time with new recipes and adventures in the kitchen. Nationwide, huge numbers of men have learned to bake bread, especially sourdough bread, sometimes injera. Some people throw virtual dinner parties.

Masks are the COVID-time fashion statements, ranging from those homemade from vacuum cleaner bags and bandanas to stylish, colorful, political, artistic face coverings. Conventional medical masks (forget N95s) bespeak boring lack of effort or creativity—or an essential health role. Companies offering diverse mask choices are legion because business, like nature, abhors a vacuum, and strives to meet every need where there’s money to be made. In addition to individuals, corporate icons, college mascots and national symbols signal their mitigation support.

Zoom and other visual online connections heighten playful anti-fashion or half-fashion. Whatever one wears below the desk top isn’t visible, creating the perfect public/private dichotomy. Visible style matters for viewers, but what can’t be seen is left up to the imagination. There’s probably more talk than performance about this category, but it will never be known for sure.

COVID-time has pushed cell phone life and small-screen entertainment into new territory. Texting was already the norm, but now it is the bothersome, more demanding norm. Answer that unscheduled phone call from an “unknown caller?” Potentially spam? Nope, wait for the message transcription. That was already early 21st century. Meetings happen with FaceTime or Zoom, or not at all. Pandemic time has become Zoom-time, broken into synchronous and asynchronous virtual meetings, in which staring into black boxes with a name on them is supposed to count as a connection. Skype and Google Hangouts are so pre-COVID, virtually 20th century. Nearly everyone was already online, communicating, working and taking care of business.

Multiply online-ness by several factors for COVID-time’s New Normal. Those who had not already surrendered to paying bills online have shifted, producing more phone apps with which to do so—and therefore even more promotional emails. Online customer service people have never been so easy to work with! Whatever real-person sociality existed in face-to-face commercial exchanges pre-COVID now occurs from six feet away and through a face mask. Cross the street to avoid close encounters. Curbside pickups, home delivery and Amazon Prime rule. Cash was already overshadowed by plastic; now it’s practically a museum item, a numismatic curiosity, like older stamps became.

Music festivals, conferences, sports seasons and Comic-Con 2020 are cancelled. Memorial services go online. We shift schedules and postpone appointments but track deliveries meticulously. Shopping is more time-driven than ever before. The virus has been politicized; attitudes even more polarized. The weaponized pandemic forces political awareness through acceptance or rejection of social distances and face masks. Going “out” for coffee or drinks happens online. Want to go to the bar that just opened? Not yet, thank you. Why aren’t you wearing a mask? It intrudes on my freedom. Handshakes, hugs? No, never again; that’s so pre-COVID.

The virus has radically changed presidential campaigns. Pace, timing, intensity are all different in COVID-times. One political consequence stands out for its time disruption: voting. During COVID-times, legions of voters do so by mail, paying attention to the strict time frame differing from state to state during which a ballot must be postmarked. Standing in line to vote counts as risky behavior, an act of political courage. American voters are used to the winner of a race being declared soon after polls close. When ballots are mailed in and counted by hand, it takes much longer. Late votes are rejected. Fears of the virus have returned much of the balloting and counting to pre-electronic times. A presidential winner in November may not be known for weeks after Election Day. This wasn’t part of the slow movement anyone wanted.

COVID-time and higher education are in a Mixed Marshal Arts cage, struggling with new educational practices and the risks of face-to-face classrooms. Education at all levels is adapting to full or partial remote instruction, training for which is a “time-suck” to some. Synchronous, asynchronous and hybrid as online teaching styles are a brave new world for both professors and students. Meetings may be among participants separated by several time zones speaking with disembodied voices. Anthropologist Susan Blum explained “Zoom fatigue”, an online version of quarantine fatigue. Clearly fatigue is part of the new COVID-time stress. “Zoom-bombing” became an educational warspeak phrase and risk. Zoom arrangements have modified Parkinson’s Law of work and time: “In lockdown, Zoom expands to fill all of a manager’s available time”. Remote work really does mean longer days.

Future planning has entered the world of “if/then” conditional phrases. COVID economic disruptions have sent tsunami waves through educational and job plans. Cancel that cruise! Study abroad? Not this year. That summer internship? Maybe next summer. That trip to Nunavut? (no cases so far!) Hmmm. Some academics have adapted to the upheaval. Harvard historian Maya Jasanoff announced her COVID plans. “I travelled a lot in the pre-pandemic world (70+ countries), but in the time of coronavirus I’m setting out on a domestic adventure: a solo roadtrip to see some of these 50 states. Got my masks, gloves, hand sanitizer, hiking boots, a pile of books, and an itinerary ready to change as the pandemic warrants. Off we go! #roadtrip #westwardho” (@jasanoff, Instagram 7/14/2020).

When I’m watching a show on TV, my automatic reactions are, “Why aren’t they farther apart? Why are strangers touching? Only crooks wear facemasks?” The psychological impacts of the pandemic may last for weeks, months, a long time. In a culture already scarred by high levels of anxiety and depression, many are likely to talk about COVID-PTSD with their therapist sooner than later.

COVID-time has provoked cathartic humor. See, for example, “Gallows Humor in the Time of COVID-19,” “It’s OK to find Humor in Some of This”, “Escape Our Current Hell with These (Good) Coronavirus Jokes”, and “50 Coronavirus Jokes that Should Help You Get Through Quarantine.” Corona beer production was halted; rebranding it as “Ebola Extra” was one of those tasteless jokes. References to Jack Nicholson driving his family to the Shining’s Overlook Hotel are not funny. The “dryness of your aggressively washed hands” is one of the “Ways to Measure Time when Time Has lost its Meaning”.

Linear time endures fitfully but can loop back and replay events in Groundhog Day fashion as the coronavirus spreads like a forest fire in windy California. “I feel like it’s March all over again,” said William Hanage, professor of epidemiology at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. “There is no way in which a large number of cases of disease, and indeed a large number of deaths, are going to be avoided.” But this is September. Welcome to the COVID time warp.

COVID-time feels fluid and rapidly changing. Scientists publish new information daily about a tiny virus unknown eight months ago. Public health projections provide no comfort. According to Dr. Anthony Fauci, “We’ve learned, painfully, that this is a highly highly efficient transmitter” affecting individuals and organ systems in unpredictable ways for different lengths of time. Uncertainty, tension and fatigue reign.

How will all this be thought of in six months? Five years? I don’t know. We’re serving time, citizens in a world of cautious “watchful waiting.” In any case, as anthropologist Kwame Harrison has written, this is “The Time of Our Lives”.

End Times are usually associated with religious extremists. Before Times has become a reference to pre-COVID days. Will we see After Times? Only time will tell.

Robert Myers, a cultural anthropologist at Alfred University has a degree in public health and has been a long-time observer of U.S. culture, especially paying attention to language, health and violence. He spent extended periods in Nigeria on a Fulbright Fellowship and in the Caribbean. Recently, he became fascinated with the High Arctic in Greenland, Nunavut, Canada, and Svalbard, Norway. He has published previously in Anthropology Now on “That Most Dangerous, Sacred American Space, the Bathroom” (April 2018), and contributed to www.anthronow.com on “The Great American Cultural Eclipse.”

2 Responses

Interesting way to avoid talking about life and death here, Bob! I was waiting for you to get to the part about “killing time,” but that is what I am doing.

True that, Tim! 👍 I’m thinking more about “serving time” these days. 🤔