How Raghad Alhallak and her family sold their home and bakery in Syria, scaled a mountain, fought off wild dogs, evaded border guards and nearly drowned at sea — before being welcomed in Germany.

The Alhallak family fled Damascus at the end of the summer of 2013, after selling their jewelry, their bakery and their home. The bombs were falling, and if they did nothing, their eldest son, Mohammad, would soon be drafted. The parents, Kasem and Hanan, carried all of the proceeds – $35,000 in cash – in nylon satchels beneath their clothes.

“Our plan was to live and work in Turkey,” recalled their daughter, Raghad. She and her twin sister, Rahaf, were 18 at the time.

“We spent two months in Ankara. But we couldn’t survive there,” Raghad recalled. “It’s hard to find a job, and even if you do, they try to cheat you. They lower your pay, because they realize you have no choice. You have to take whatever they give you.”

Losing heart, Kasem and Mohammad, who was 16 then, decided to leave for Germany, the country most Syrians seemed to consider their best destination.

Kasem tucked $15,000 into his pants, and left $20,000 with his wife, funds meant to provide for their twins, their younger son, Ahmed, then age 11, and their youngest daughter, Rayan, then 9.

The family was overjoyed to hear that Kasem and Mohammad had arrived safely in Bonn, and were expecting to be offered asylum. But soon the implications of their accomplishment set in. When and how would the family ever be reunited? They’d heard the stories of other refugee families being scattered among countries, and separated for years – years that threatened to stretch into lifetimes, as refugees often have no choice of where to settle.

Hanan Alhallak was determined that this would never happen to them.

Raghad had just finished her freshman year in law studies at the University of Damascus. She spoke English, and soon assumed the role of family spokeswoman.

***

We met in Izmir, Turkey, in July 2015, as Hanan, Raghad, Rahaf, Ahmed and Rayan were making repeated attempts to cross the Mediterranean into Greece. A cousin, Rana, and her husband, Rawad, had joined them, as had one of Rawad’s friends, Yasen. Malek, a teenager nobody knew, had also attached himself to their group along the way.

One night, Raghad recounted, they were told that the sea was too rough, and they were returned by their smugglers to Izmir. Another night, they thought they’d reached Greece, but it turned out that their boat had only reached another part of the Turkish shore.

And then I heard no more from her.

She didn’t log on to her Facebook page, and I saw that my messages to her had not been read.

I kept thinking about her: had their boat been one of the unlucky ones, and capsized in the Mediterranean? Had they died a horrible death at sea? Or had some other misfortune befallen them, such as a robbery or catastrophic injury?

Such crossings would only be attempted if one was at wit’s end, as the Alhallak family and hundreds of thousands of other migrants clearly were.

A year later, Raghad and I reconnected, and she agreed to tell me her story.

***

“My father was scared for us. He was telling us, ‘don’t come.’ But my mother insisted. She told him: ‘We can’t live without each other!’ And we all missed him. Finally, he agreed.

We needed a smuggler. But we wondered: ‘How can you find somebody to trust?’ We met various people who offered to help us, during our week in Izmir. You can’t trust a lot of the men there, in Basmane [the Izmir district where many refugees congregate], because there are a lot of liars, and sometimes they are dangerous. We would see some of them around at night, drinking beer and going to the casino. So we felt we couldn’t trust them.

Finally we hired someone to take us across the sea. He was Syrian, but our driver was Turkish. They put us in the kind of truck you use to carry animals. There were 40 of us, and we stood up in there for two hours, while the Turkish guy drove. We were so tightly packed in that we could barely take a breath.

When they opened the door, we did not see the sea. We were next to a mountain! How were we going to climb up there? We had small children with us – toddlers of two and three years old! We were in a dark forest. We couldn’t see anything, and they told us to turn off our phones, because the police can track you when a phone is on – and also someone might see the light.

‘Where are we?’ we asked our Syrian contact.

‘Oh, don’t worry,’ he told us. ‘We are only about five minutes from the sea.’ It was 10 o’clock at night. Our Syrian smuggler told us to start walking on this mountain.

The path was very narrow. With your next step, you could tumble off the mountain. I’m afraid of heights. I was so scared, and I started to cry. But I couldn’t do anything about it – we had no choice but to keep going.

We walked and we walked, and we walked and we walked.

I became separated from my mother and sister and brothers.

The man in front of me walked far ahead.

And suddenly, I was in the lead. ‘I don’t want to be first!’ I screamed.

I was so tired that I couldn’t take a breath. My sister fell, and she couldn’t get up. We couldn’t carry our bags up that mountain. They were too heavy. So we began throwing away our things. We had to throw away our life preservers, both the black rings and the orange vests. I threw away a lot of scarves. The worst part was leaving behind our remembrances. We had to leave behind our photos from when we were children, our letters and all of our mementos. I could only keep my Koran.

We walked and we walked. And walked and walked.

Finally, the sun began to come up. I saw that we had arrived at the top of the mountain. And yet, even from there, we couldn’t see any sea.

In the daylight, we could not walk, because the police might see us. ‘You will stay here until tonight,’ we were told. Our smugglers left, but their Turkish assistant stayed behind with us. It was 5 a.m.

We’d thrown away our food and our water, so we were hungry and thirsty. I slept for maybe 10 minutes, but the smuggler’s assistant wouldn’t let me sleep.

By now, we didn’t know whether we would even live to reach the sea. But at 9 o’clock that night, when it was dark, the [Turkish] smuggler returned. Now we had to walk down the side of the mountain. This turned out to be even harder.

I saw a snake. I heard them moving in the trees.

And then my mother fell. She fell and broke her arm. And she began to cry. Our Turkish smuggler began to panic. ‘Sus, sus,’ he kept telling us. ‘Be silent, be silent.’

My mother was crying. ‘Leave me, go on without me,’ she was insisting.

And the Turkish guy was saying, in his language, ‘Leave her, leave her and follow me.’ But the group wouldn’t allow this. They picked my mother up and carried her. Then they helped her walk.

And finally, at 4 o’clock in the morning, we saw the sea.

But there was a surprise waiting for us. The police were on the beach. By then, I was happy to see them.

Our smugglers ran away and abandoned us there. For two hours, we hid behind the rocks. Finally we decided to show ourselves and to give ourselves up.

The police turned out to be friendly! They didn’t arrest us. They left us alone, but they did take money from us – 100 Turkish lira (about $35) per person. Then they brought a bus for us, and returned us to Basmane.

Once I was in the bus, I realized how terrible I smelled. One of the Turkish guys who was taking us back to Izmir moved away from me.

But we didn’t give up. Even though my mother was crying, even though she was in pain, with her broken arm, she was determined to keep going.

As soon as we got back to Izmir, we interviewed another smuggler. ‘There is a trip tomorrow,’ he told us. He took 1,200 euro from each of us.

This was our third try. We took a taxi, and rode for two hours. I slept in the car. My mother tried to keep our spirits up. ‘Don’t be scared, I am with you,’ she kept telling us.

It took two more tries to actually make it into a boat. Once the sea was too high. Another time, the police were near again.

The boat we eventually took was made of rubber, and there were 40 people in it. It was pitch black on the beach. Our smuggler took three people aside to show them how to pilot the boat, and selected one person to teach him how to drive.

I was so scared. I told myself, ‘I am not going to live, I am not going to live.’ I was also afraid for my family. I thought that was my endpoint in this life. It was my most desperate moment. I will not forget that feeling.

The Mediterranean Crossing

So we climbed into the boat. One of the passengers was a 17-year-old girl with her husband, and they had a daughter just two months old, and a son of one year and a half. The girl was crying, and I sat near her, and told her not to worry – that we will be ok, and to be calm. I told her that we would make it, and that we would live, even though I didn’t feel that confidence myself.

She calmed down, but when the boat began to move, she burst into hysterical tears. She cried and cried. My heart also sank.

Two minutes later, the motor stopped. Three men jumped into that cold water in the dark, and finally managed to start the motor. But we knew we wouldn’t get anywhere; if we tried to leave in that boat, we would drown. So we returned to the beach.

I was happy: I was alive, and my family was alive. The sun was coming up, and on the beach our smuggler announced: ‘There will be no travel today; you will go tomorrow.’ And now I knew I had another day to live, and to prepare myself.

Our smuggler owned a restaurant on this beach, and he brought us bread and water. Later, lots of people came to the beach to swim and play. My brother and sister started swimming, too. My sister loves the sea, and swimming. It was a lovely day. But when it got dark, all of the people went home.

And still we were waiting on the beach. We waited until 4 o’clock in the morning. That night, the sea was so calm, and we were, too.

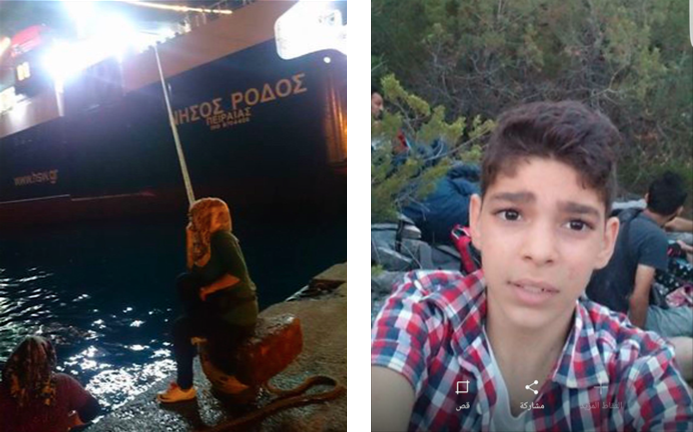

We were headed to an island in Greece. After just two hours, we saw the island! We were so happy to see it so near.

But now we were afraid of the ‘commandos,’ the Greek police [some of whom have reportedly gone rogue, and were said to be robbing migrants in mid-Mediterranean]. We knew that, if you weren’t drowning, they would return you to Turkey.

So one intelligent person among us lifted a stick, and popped our boat! When I heard the noise, at first I thought someone was shooting at us. The boat began to deflate, and water starting coming in. We were screaming, and starting to go under. We had started to drown.

The Greek police saw us from a distance. ‘Please, please, help!’ we were shouting in English. ‘We have children on board!’ And we lifted up some of the children, so they could see them.

Their boat came closer. There were two commandos inside. But they made no move to help us; they were just shooting video. They circled us, took some videos, and then left.

We had heard stories of people leaving their boats, and trying to swim to Greece at this stage. There was a story of a man who was a competitive swimmer; he jumped out of his boat, and swam to Greece in half an hour.

No one on our boat tried this.

More and more water was pouring in. We started bailing it out. We were sinking. We thought we were at the end of our lives. We were there for nearly an hour.

Then another boat arrived. We’re screaming, ‘Help, help, help!”

First the police on this boat started shooting some video, too. They circled around us. They started calling out in English: ‘Be calm. We will save you if you are calm – don’t worry!’

And then a big boat came, and a ladder was extended from their boat to ours.

I was so happy. That may have been the happiest moment of my life.

We were taken to the beautiful island of Samos, on a big, quick boat. It took only a half an hour to get there. The police took our pictures, our fingerprints and information about us, and gave us each a piece of paper that would allow us to go to Athens.

We booked passage on a big ship. And then we slept under the stars.

An Overland Ordeal

We arrived in Athens at midnight, and ate pizza. It was delicious! Then we booked into a hotel, where we planned the next part of our journey. What I didn’t understand then was that the toughest and scariest days were still ahead of us. We were about to travel for another 2,400 kilometers (1,491 miles). We were planning to walk all the way to Germany.

From Athens we traveled with different people. Each of them took different amounts of money. First, at the hotel in Athens, we met with a man who said he would take us by car to Salonika, about 450 kilometers away. He took 100 euro from each of us.

From Salonika, we were handed off to a person who promised to bring us across the border into Macedonia. We walked for an hour and a half through the forest, and met with the border guards, who were very friendly toward us, and gave us two choices: We could take the train across the region, nearly to the Serbian border, or we could accompany them to the police station.

‘OK, thanks,’ we told them. ‘We’ll take the train.’ That train was so hot, and we didn’t have any water. The trip cost 200 euros per person. We were so tired that we slept on the floor of the train. Finally, at 9 in the morning, we arrived at the Serbian border.

Nearly 200 of us started walking together through the Serbian forest. But the police separated us into groups, and by the time we reached a Serbian village near a camp, we were just 15: my family, and a few others.

I can’t remember the name of that village. We saw of lot of small houses, and understood that Bosnian Muslims lived there. But they were afraid to help us. We passed a big house, where a wedding was taking place, and heard music coming from inside. The women were wearing beautiful dresses, and the men, too, were all dressed up. They were driving beautiful cars. We didn’t go inside, but some people at this celebration came outside, and gave us food.

There was a camp in the village, and we knew we would have to go inside. The camp was very full; you had to wait your turn just to get inside. There were something like 200 people waiting outside the camp. But, because we were a family, and because my mother’s arm was broken, they let us go inside.

Inside the camp was another processing system. There were three steps. The first step was waiting outside to enter. The second step, inside the camp, was waiting in another long line to take a number. And then came the final step: you take your number, which will allow you to travel legally through Serbia.

But here the police were angry and unfriendly. At the second step, at 7 o’clock, the police stopped giving out numbers, and you had to stay where you were, and just drop down and sleep under the stars.

As we waited out there, my sister Rahaf fell down. The police took her inside alone to see the doctor. Being separated like that was very difficult for the rest of us. But my sister came back, and we put on all of our clothes to protect ourselves against the cold. When we woke up in the morning, at 7, we waited on line some more.

My number was 753.

We waited another five hours. A Serbian guy walked along the line, calling out numbers, and saying if you had that number, you could go to the office. Finally, we heard our numbers called.

They asked us questions, such as, what were our names. They took our photos and fingerprints. Then they gave us papers to leave the camp.

I thought: ‘Finally, I am a free girl!’

We took a train to Belgrade, the Serbian capital, which cost 200 euros per person. We were so tired that we slept on the floor of the train. We took a taxi into the city, and the driver charged us 100 euro to take us to a hotel. The hotel wanted 250 euro from us for just one night. But we had to do it – we needed to sleep and to take a long shower.

Because we knew that the most difficult step was ahead.

Sneaking into Hungary

We were almost out of money. We had nothing left to pay guides and smugglers. We knew that now we would have to travel alone. That’s why we decided to try to cross into Hungary by ourselves, with just two men and one woman we met, who were traveling with two kids.

First, we bought some new clothes, because the weather was cold, and we didn’t have heavy clothes, which were necessary for walking in the forest.

At the border, we met a farmer. He was taking groups to the path, because he knew the way. He took 100 euro from each person, and then he and his donkey would walk with them to the path. Then he would leave them, and go back and get the next group. We waited our turn, then walked for one hour with this man. Then he went back to get the next group, and left us alone. We had been a group of 30 walking together, but now it was just my family, and five others: a couple, another man, and two small boys who had come from Syria alone.

After about two more hours’ walking, we saw a highway in the distance, and lots of cars passing by. We got excited: we thought we’d arrived at the border. We realized that we would have to put on our good clothes, and get ready to be friendly. We would need to send someone ahead to ask the way.

I volunteered to go. The group accepted my offer, and the little guys came along with me. I walked up to the road with a confident air, although actually, inside, I was terrified. We reached an old building, and a man inside looked at us sharply. So we passed him without stopping. But in front of the road was a high electrified fence. I was shocked and sad. I hated to have to return to my family and deliver this bad news.

As we retraced our steps, the man came out of the building, and began talking with us in an angry voice. But I couldn’t understand what he was saying. I tried speaking with him in English, but he didn’t understand me, either. And I understood that we could have been killed, and that he could have taken our money. But, thank God, he left us alone, and I was able to return to the group. We realized then that we were still in Serbia.

Eventually we reached a police post. ‘Come over here – and don’t make any false moves!’ one policeman shouted at us.

‘OK!’ we answered loudly.

He began walking toward us. But then he began murmuring, in a low voice, ‘When I say three, run into the forest.’

He counted: ‘one, two, three!’ And at ‘three,’ we ran into the forest. The other police followed us, but they didn’t catch us.

We were all crying by then.

A Brush with Death

I passed some of my worst moments in Hungary, as we walked through a dark forest alone. We all wanted to turn back. But we couldn’t. Malek climbed a tree, to see where we were. But as far as he could see, he saw only trees.

We had no food, and no water. Our phones were not catching any GPS signal. And we had no one to tell us the way.

We walked and walked, for hours and hours.

Suddenly my mother saw a light behind us – the kind of light that follows you. We thought they were robbers, so we tried to keep hidden in the trees. We heard them running – so we started running, too. I thought we were going to die. Because these people will kill you. Eventually we lost them.

But this last scare took everything out of my mom. ‘I cannot go on,’ she told us. ‘Leave me here!’ We refused to leave her. We let her rest, and tried to give her hope.

Eventually, we all started walking again.

At midnight we came to a big abandoned house. We kept going, and saw another big house. A light was on inside. And outside were two big black barking dogs. I couldn’t breathe. I stopped to pray; I read from my Koran. I put my family in front of me, and brought up the rear, to make sure everyone would be safe.

And then up ahead, I heard my mother scream. One of the dogs had caught her. I heard him barking and growling. I thought: ‘The dog is eating my mother!’

I stopped, and waited. I waited for it to be my turn to be eaten. Because I cannot live without my mother, and there is no escape from the dogs.

Suddenly, from deep in the forest, I heard classical music playing, and the sound of cars. We heard footsteps. It was like being in a horror film.

At that moment my little brother returned. “Maaaaaamaaaaaa!” he screamed. He, too, thought my mother was finished.

We turned our heads, and suddenly saw that the dogs were on very long, long chains. They could not catch us – they could only bark at us.

I told myself that, if anybody asked me what the worst moment in my life was, I would know what to say: it was this one, when I believed my mother had been torn apart and eaten by dogs, and that my turn was next.

By now, my mother could no longer speak. She was in shock. But somehow she tried to comfort my sister, and tell her not to be afraid – she reminded her over and over, that we were alive. Alive!

And we sat there on the ground, because we couldn’t walk anymore.

By the time we came out of the forest, and reached a farm and a road, I had taken off my scarf. My hair was full of twigs and dirt.

A car stopped, and the driver asked if we wanted to go to Budapest, for 500 euro each. Only the five us – the members of my family — went in that car.

We knew better than to pay in advance. ‘If we arrive in Budapest, I will pay you,’ I told the driver. And we did.”

***

In Budapest, the Alhallaks and their relatives bought and changed into black clothes, and were smuggled in a big black BMW into Austria. They then took a bus to Frankfurt. Rana, Rawad and Yasen left for Hanover, while the Alhallaks traveled by train to Bonn, arriving at 7 a.m. on August 2nd, a Sunday.

Raghad was about to turn 21. She and her family had traveled some 4,727 kilometers (2,937 miles), and had traversed seven countries. They’d been on the road for nearly a month.

The next day, Raghad wrote on her Facebook page:

“After a month of misfortune and displacement, of drowning, of forests and dogs, of insects, of cold and nipping, of sleeping on rocks under the moonlight… of escaping from police and fear of the fingerprint… my family and I arrived safely in Germany. A thousand praises and thanks be to God… and I returned to the bosom of the greatest father in the world.”

Kasem Alhallak came to meet them at the bus station. And he asked his daughter: “Where is your scarf?”

Epilogue

The Alhallaks were placed in a camp, where they stayed until September, and were then assigned temporary housing in Bonn. In May 2016 they were moved to their current home, a pleasant, three-bedroom apartment in a leafy suburb about a half hour outside of the center. The German government will support them there for three years, allocating each person a modest 300 euro stipend per month, while the Alhallaks study German and pursue job training, language instruction and schooling. After this, they will be allowed to stay in the apartment – but will be responsible for their own support.

Kasem, 55, hopes not to reopen a bakery, but to once again work as a mechanic and car body restorer, as he did for 12 years in Dubai. Raghad hopes to switch her course of study to something in the medical field, as she had wished to do in Syria but lacked the grades to enter.

Hanan’s arm was splinted, first temporarily in Serbia, and then permanently in Germany. It has now healed.

“She’s like a man,” Raghad said proudly of her mom.

But despite the hospitality they’ve enjoyed, and their relief at being reunited in a safe new home, German culture still feels alien to them.

We met during Ramadan, the annual Muslim religious observance marked by 30 days of daylight fasting. That’s an especially difficult obligation in German summer, when darkness doesn’t fall until at least 10 p.m. But Raghad loves the holiday season, and claimed not to mind the long hungry hours.

What she did mind is missing out on the shopping, partying and late-night festivity of Eid, the end-of-Ramadan celebration, which also fell during my visit.

Instead of cooking traditional foods, or planning a celebration, Kasem and Hanan sat stiffly on their comfortable new couch, as if unsure of how to throw a celebration in such a strange environment.

There are of course thousands of other Syrians here, as well as thousands of Turks, who were likewise celebrating Eid, the holiest day on the Muslim calendar. But the Alhallaks never managed to arrange a party. “Are we celebrating?” Raghad asked her mother.

Hanan shrugged. They ended up treating Eid like any other day, as most Germans would. Raghad instead followed the celebrations of friends and relatives, in Syria and elsewhere, on her Facebook page.

“This is what I miss most,” Raghad said. “Friends, family and celebrations.”

For all the Alhallaks have gained, Raghad’s sentiments also point to what they’ve lost: the warmth of a community, and comforting traditions all immigrants end up leaving behind in their former homes, or altering in their new ones. In that way, they’re no different from any other immigrants who leave one country for another.

And there are scars. The lush woods beside her house, so beloved by Germans, remind Raghad of her forest ordeals, so she won’t go inside. Nor does she date, the way most Germans her age would (in fact, she’s evading an admirer, by pretending on her Facebook page that she lives in Berlin).

But the Alhallaks are giving themselves time to adjust.

“I came to Germany for our future,” Kasem said. “In three or four years, we’ll see what we do next.”

“For the future of our children,” Hanan added.

***

Raghad Alhallak, formerly of Damascus, Syria, lives with her family in Bonn.

Raghad Alhallak, formerly of Damascus, Syria, lives with her family in Bonn.

Mary D’Ambrosio, an assistant professor of professional journalism practice at Rutgers University, specializes in writing about international issues. Her work has appeared in the Huffington Post, the San Francisco Chronicle, Newsday and the Miami Herald, and in Global Finance, Working Woman and Islands magazines. She has a B.S. in magazine journalism from Syracuse University, and an M.Sc. in economic history from the London School of Economics. Reach her at mary.dambrosio@rutgers.edu.

3 Responses

Thank you for doing the hard work to bring this amazing first hand account to readers

Thank you for sharing your story Raghad and thanks Mary for bringing it alive. This will be an inspiration to persevere for many others!

This is the most inspiring story for all “Syrian” and other refugees facing the same situations in their countries right now to motivate them how to fight bravely for their rights and living life peacefully.