Jessica Marie Falcone

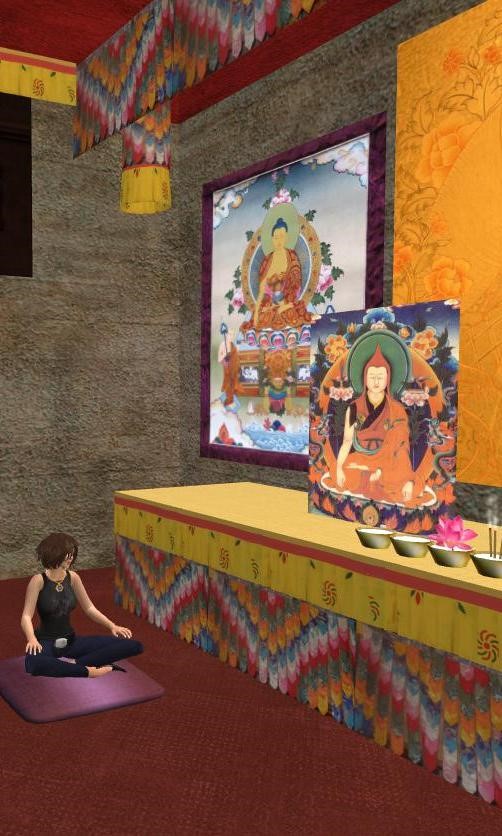

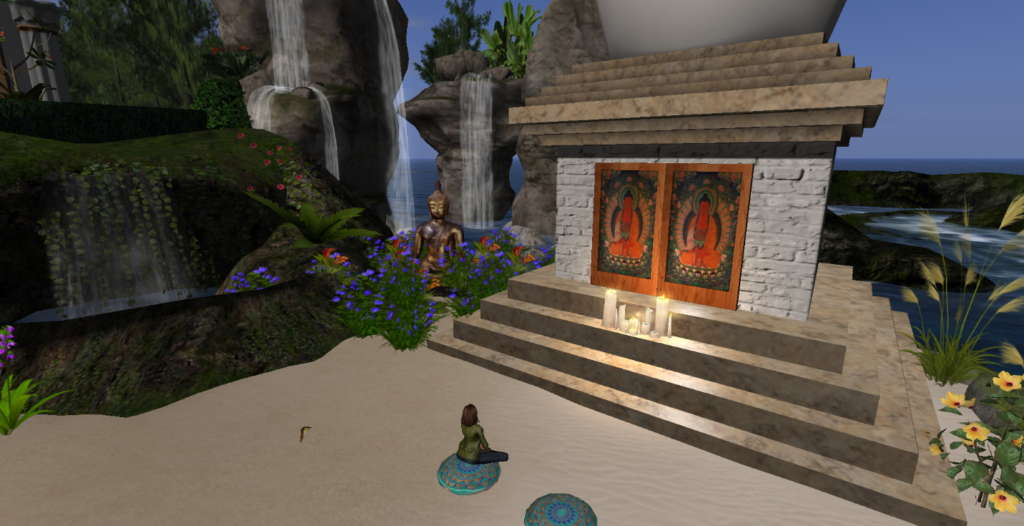

As I logged into the virtual world of Second Life (SL) in October 2020, I was expecting my avatar to manifest in the Buddha Center where I had left her a few months before (www.secondlife.com). The Buddha Center was an online Buddhist teaching community where I had already done years of research (see Figure 1).[1],[2],[3] But as my avatar took shape and the landscape sorted out its features on my computer screen, I realized that my avatar was somewhere unfamiliar. Instead of virtual manicured lawns and Buddha statues, I saw virtual forest, wild and overgrown with bright little fairies flitting about. My mouth dried out as my spine straightened in agitation. I quickly tried to jump to my most common “saved places” from the Buddha Center locale. I looked for the main stupa—nope. Deer Park, no. The tea room, not there. The Buddha Center was gone.

This was not the first such shock I had experienced in Second Life, but it was by far the most upsetting. Although I was no longer a regular attendee of meditations and teaching, I felt a wave of sadness about the loss of a place I had valued and visited for a decade. I hastily checked the directory as a new hope germinated inside me: maybe it had just moved?

The Buddha Center was still in the directory. But there was no swell of relief yet, as I knew very well that the SL directory can be as out-of-date as an old phone book. I teleported using the directory coordinates. Once again my avatar gradually took shape on unfamiliar terrain, but to my considerable relief, this time I also saw things I recognized. Just within view was a set of meditation cushions arrayed in a semi-circle around a Buddha statue, with animated deer grazing here and there. It was recognizably the Buddha Center’s Deer Park, albeit somewhat altered. After exploring for over an hour, I understood that the Buddha Center had not just moved, they had reduced their digital footprint considerably. The new posted schedule was pared down, the grounds were a fraction of their former size, plus many of the non-religious community meeting spaces had been removed or downsized.

Although the Buddha Center had not done this before, it made a certain amount of common sense: the monthly rent to the virtual world platform, Linden Lab, would be far cheaper. “Ah,” I thought to myself, “It still exists. Thank goodness.” The Buddha Center had not yet joined the ranks of no-longer-places, and I was glad for it.

Although it might seem strange to some readers, I am hardly alone in being emotionally invested in a place I care about in a virtual world. With the opportunities afforded by new digital media, many people have extended and innovated their identities, practices and cultures into virtual spaces. Not long after virtual worlds first emerged in the mid-1970s,[4] the subcultures therein became grist for the mill for social scientists who have faithfully traced the broader impacts of their development over time on people and cultures around the world.[5],[6],[7],[8] During my own stretch of ethnographic research on the robust Buddhist religious practices and subcultures of Second Life from 2010 to 2012, and then again on and off starting in 2018, I observed a community of practice where people from around the United States (and the world) came together and made connections based on their shared interest in Buddhism. I observed as social and spiritual connections developed among teachers, volunteers, students and builders. But I also observed the transitory nature of the community as people came and went. In addition, the digital spaces people inhabited in SL as things were regularly changed, sharpened, edited or upgraded. In this essay, I will background the very active social life of SL actors and discuss instead the flip side of digital sociality—the digital mourning and loss that can occur as familiar spaces melt away. I would like to suggest some frames for thinking through digital loss and impermanence, which is both omnipresent and sometimes invisible in the contemporary “online a lot of the time” social world.[9]

Virtual worlds are non-physical, but they are places nonetheless. In the documentary, Our Digital Selves: My Avatar is Me, anthropologist Tom Boellstorff—who has done substantial, innovative research in SL[10] — emphasizes that virtual personhood unfolds in virtual space over time: “Embodiment is emplacement…The avatar has to be in a place or it’s not an avatar, it’s a screen shot” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GQw02-me0W4). Further, Boellstorff observes that the unique opportunities for sociality in a world such as Second Life exist because the places are available to a multiplicity of actors, to interact with as they will. He goes on to say, “If I have Second Life on my computer and I turn my computer off, it’s still there. So, it’s a persistent place where I can build something and I can log off, and someone can come and look at it. Or add to it. And that persistence of place allows for social relations and other kinds of things to happen that couldn’t happen otherwise.”

Persistent, yes. Permanent, no.

Both actual and virtual spaces are the shifting sands upon which humanity builds its cultures, and anthropologists work to understand how humans occupy these places in time and how they face their inevitable loss. While archaeologists study the material remains of long buried human settlements, cultural anthropologists have diligently studied contemporaneously receding, disappearing actual life places. These include, for example, rapidly deforested spaces,[11] melting glaciers in Iceland[12] and indigenous spaces in northern Paraguay that are being swallowed by expanding agro-business,[13] to name just a few. Understanding humanity requires understanding what humans make, preserve and destroy or allow to fade away.

I hope to complicate Andrew Hoskins’ notion of the “end of decay time,”[14] in which he argues that digitally mediated sociality has essentially immobile, permanent, archival qualities. He writes, “The avalanche of post-scarcity culture and the databasing of the multitude challenges decay time. Suddenly, the faded and fading past of old school friends, former lovers and all that could and should have been forgotten are returned to a single connected present via Google, Flickr, eBay, YouTube and Facebook.” Insofar as virtual archives are sometimes conceived of as cultural repositories—from corporate online digital photo archives such as Shutterfly to academically formulated digital archives like the PeruDigital (https://create.cah.ucf.edu/initiatives/perudigital/) interactive environment that can serve to connect users with their heritage places or as virtual tourists or the multimedia digital archives of Digital Himalaya (http://www.digitalhimalaya.com/)—the virtues of relative persistence must be taken up alongside the anxieties that Hoskins remarks upon. However, if relative persistence is one side of the digital coin, then the precarity of virtuality is the flipside. While Hoskins is focused on the not-insignificant problem and possibilities of what digitally persists, here I am more interested in exploring the ephemerality of what does not.

Digital Ruination

As a virtual world founded nearly two decades ago, Second Life may not be as cutting-edge and popular as some of the newer digital worlds, especially those already using 3D virtual reality headsets. But it is still going strong. The Second Life platform is corporately owned and managed by Linden Lab, but the vast majority of the places and things in SL are created by users. In SL, people can enable their avatars to do almost anything, such as fly around to see the sights, build furniture for their homes, dance with other people in whatever outfits they fancy, attend an exhibit of virtual art, make connections to other people and even engage in spiritual practice.

As an anthropologist of Buddhism, I came to SL to try to understand why some Buddhists were choosing to practice there and how they did so. When I started preliminary explorations of Buddhism in Second Life in the late aughts, I was fascinated by the “Heartwood Forest Monastery” and its monastics and meditators. I also looked forward to studying the pilgrimage routes of the massive Bodhi Sim, where an avatar could circumambulate a simulation of Mt. Meru, or do three-point prostrations in front of Kathmandu’s Swayambhunath stupa. I was similarly interested in the Potala Palace construction site in SL— organizers hoped the build would faithfully replicate the Potala in Lhasa, Tibet, so that the Dalai Lama could occupy his rightful place, if only virtually. As I explored Buddhist sites in SL, I noted these and others as potential spaces to study virtual Buddhist engagements. However, when I re-engaged with SL in earnest several months later at the outset of fieldwork proper in 2010, I was surprised to learn that none of those three places existed in SL any longer. They had each run out of steam, and collapsed due to the unmet need for more donations. Pieces of those three builds may still be out there in code (perhaps on file at Linden Lab, or in builder inventories), but the virtual places were no longer accessible in Second Life. They had become offline non-places, or what I call no-longer-places, their virtuality made even more explicit by the ease with which they disappeared.

Tom Boellstorff and his collaborators note that contemporary ethnographers ought to take care not to write as if they are representing a subculture that is fixed in time, and how this is especially important for those working in virtual spaces that change and shift quickly: “In looking over our past work, all of us certainly feel relieved that we used the past tense. World of Warcraft no longer has sixty levels…At this writing There.com had closed and was about to reopen, and Uru had closed and reopened three times since Celia began her initial research with the Uru diaspora…All ethnography inevitably becomes history.”[15]

Boellstorff and his co-authors are right: virtual spaces are especially fluid and changeable. In his ethnography on virtual Buddhism, Gregory Grieve noted that he and his research assistants could not keep pace with the relentless comings and goings of religious landscapes in SL. He wrote that “…when we first started fieldwork, my team attempted to catalogue all the religious regions by landmarking them, but after mapping over five hundred, we stopped. The problem was not just with the sheer number but that, like ice in a quickly flowing stream, the places were forming and dissolving at such a rate that it was difficult to give an accurate count. Unlike the actual world where abandoned buildings leave ruins, in Second Life all that remains is an error code.”[16] In addition to error codes, sometimes blogs and chat rooms still online refer to virtual spaces that are no longer extant and these are significant traces as well.[17],[18]

As I sought a framework for discussing digital ruination, I combed the literature for work on virtual ruin, loss and disappearances. Here is my working typology of digital ruination: 1) digital “ruins” or digital ruins-by-design, which are spaces intentionally built to resemble ruins; 2) socially-vacated persistent digital spaces, which are largely emptied, abandoned and under-used virtual spaces—not by design, but just as a matter of fact; 3) “no-longer-worlds” (popularly known as “abandonware”) which are whole virtual worlds that are no longer attached to the servers that once made them widely available for play, use or exploration; 4) “no-longer-places” are once-persistent places that have now disappeared from still extant virtual worlds. Any of these virtual phenomena may or may not be saved for posterity in digital archival preservation, but it is worth nothing that as far as the typology goes, the first two—digital “ruins” and abandoned spaces— are contemporaneously persistent, while latter two—the no-longer-worlds and no-longer-places— are formerly persistent places that have been rendered unavailable to digital actors.

Persistent Ruins: Ruins-by-Design and Socially-Vacated Persistent Spaces

Digital “ruins” were built to evoke the illusion of collapse and decline. The presence of “ruins” (or ruins-by-design) in digital spaces can be part of active social lives online, such as when virtual actors explore an ancient castle whose busted gates are already falling off rusty hinges. Hoskins is correct when he notes that digital “ruins” are not subject to the vagaries of organic decay. He writes, “Before the digital, the past was a rotting place. Its media yellowed, faded or flickered, susceptible to the obscuration of use and of age. And wherever it was collected and contained, the media archive concentrated emissions of volatile organic compounds: the fusty smell of a second-hand bookstore or library was a mark of age which accompanied the visible signs of use and decay.”[19] When journalist Laura Hall revisited SL some ten years after her first trips there, she noted that “removed from organic decaying processes, the only ruins in this world, including simulacrum of piles of dirt and construction vehicles, are ones that have been deliberately built and placed there by a designer.”[20] While natural aging and ruination are not viable in virtual venues, there are certainly virtual sites in which the simulacra of ruination evoke the aesthetic of age and decline (see Figure 2).

A tour of SL at the time of writing in 2021 still yields countless ruins-by-design, and they exist in many virtual worlds. For example, Andrew Reinhard writes about the game, No Man’s Sky, in which ruins-by-design were created by “procedural algorithms” that led to the creation of a post-apocalyptic space that gamers could explore. As a site for a relatively new sub-genre of archaeology called archaeogaming, Reinhard led work on surveying the world, cataloguing types of what he calls “pre-ruined ruins” and taking note of glitches and anomalies.[21] Another good example of ruins-by-design are the virtual replicas based on the work of professional archaeologists. For example, a group of scholars collaborating on the Archaeology Island build in SL write, “The virtual world contains recreations of archaeological sites in Belize, Cyprus, Pennsylvania, and an underwater site focused on a shipwreck in Lake Ontario, all based on archaeological data”[22],[23] (see Figure 3).

Virtual ruins-by-design that are in active use contrast with the socially-vacated persistent spaces in virtual worlds that merely sit unused and neglected. Laura Hall writes of some particularly neglected spaces in SL: “But despite its empty spaces, the world still feels full of possibility, perhaps specifically because it’s all still standing strong, so many years on. It’s not abandoned; it’s simply waiting.”[24] There are plenty of these vacant virtual spaces just waiting for someone’s avatar to teleport in.

Places which are fashioned and then left to just stand underutilized or unoccupied hold their own special kind of eerie significance. For example, Minecraft is a vast virtual platform that allows players to build their own spaces, many of which are abandoned as users stop logging in, or as particular servers go offline. One Minecraft player, Matt B., has started searching the virtual world to find hidden, abandoned spaces that tell interesting stories, such as signs erected to communicate grief about departed loved ones or missed connections. Matt B. once found a cave built under a house festooned in signs that suggest the builder was suicidal: “‘If I kill myself tonight: the stars will still disappear,’ one of the signs read. ‘The sun will still come up, the Earth would still rotate, the seasons change…’”[25] Matt B. has solicited dozens of volunteers from Reddit to assist him in uncovering the stories still held in some of Minecraft’s abandoned spaces.

Archaeogaming, specifically as far as in-world virtual research is concerned, is arguably well-suited to the study of un-peopled spaces in which sociality has run its course. Andrew Reinhard has argued that archaeogamers can productively work in these abandoned spaces, and with abandoned objects, as available: “So what happens to these abandoned worlds still populated by never-aging NPCs [non-player characters] who might wait years to assign quests that they used to assign thousands of times a day? The landscapes and structures remain unchanged…The notable thing about these abandoned spaces, just as we see in abandoned archaeological sites, is the lack of life in the form of people actively using the space. The kinetic energy is gone, as is the random element of play by the invisible operators of avatars.”[26]

Persistent ruins are both still accessible to our avatars, which is the only thing ruin-by-design and socially-vacated persistent spaces have in common. In terms of design intent, these places are completely at odds with one another. In ruins-by-design, our avatar stands by broken, mossy walls, imaging the smell of decomposition, as the builder intended. Socially-vacated persistent spaces places are ruins-by-accident; they were built for action, but sit empty almost all the time now. All of the builders of public religious spaces in SL whom I have interviewed say they want their spaces to be full, alive and active. Socially-vacated persistent spaces in SL—whether religious, corporate or party spaces—could be processed by bystanders like me with a tear or a shrug, but make no mistake, they are no longer fulfilling their builders’ hopes and dreams.

No-longer-worlds: Reflecting upon Abandonware

Persistent “ruins” and the now-empty socially vacated persistent spaces described above stand in stark contrast to nonpersistent types of virtual ruination. The many deleted, inaccessible places of Second Life (and other virtual worlds) cannot be stumbled across or unburied with little digital shovels. They are lost—whether digital ash or unsettled code locked away from everyone forever—and they are only available through trace snapshots and human memories. Although Hoskins fetishizes the digital as a space of veritable permanence, he does note, in an aside, that “paradoxically,” there is a “…new scale of vulnerability to instant decay: corruption, disconnection and deletion.”[27] Many whole virtual worlds have shut down, built-then-unbuilt, and the closures are often accompanied by articulations of loss from players or inhabitants. In a conference paper, Evan Conaway spoke about what is commonly known as abandonware—the online games that have been shut down and closed by their corporate owners when they cease to be financially lucrative, or otherwise unwanted—he challenging the audience to consider, “What happens when a game world is condemned to the fate of being perpetually offline?”[28] This is a provocative question for a generation so firmly ensconced in digital sociality.

Ken Hillis writes that the online person is a part of the new reality of much human sociality today, “…producing order and new forms of mediated social cohesion” including the fetishization of the avatar as self.[29] Given the development of community, identity and memory in virtual spaces, it should not be surprising that people demonstrate attachment to virtual spaces and feel loss when that attachment is undermined. For example, as World of Warcraft’s official space and versions shift, some of the older worlds are resurrected on unofficial (and therefore, illegal) legacy servers. These underground spaces are eventually, invariably discovered and forced to shut down by the Blizzard corporation that owns World of Warcraft, much to the consternation of a committed virtual fandom. When a popular legacy server shut down in 2016, many of its 150,000 users protested online and via petition sites; in the legacy server some avatars participated in a “suicide march” to kill off their characters themselves before being killed off by the server shutdown (https://www.polygon.com/2016/4/11/11409436/world-of-warcraft-nostalrius-shutdown-legacy-servers-final-hours). In the article comments, a user notes that the existence of older versions of World of Warcraft may haunt the Blizzard corporation. He writes, “They don’t want to see their old world living. As far as Blizzard is most likely concerned, the old world isn’t nostalgic, it’s a regression of their work. People can say what they want about Blizzard, but one thing is painfully obvious. They’ve gone through an enormous amount of work to create a world that feels like it’s alive and evolving over time. A world that has history and scars from its past. Stories that can be passed down. In their mind, this illusion is broken when the memories of their old world are just a click away. The magic, so to speak, is lost.” After watching a video of the end, one commenter wrote, “Damn, that’s pretty fucking tragic now that I actually see it. Those last moments must have been an amazing sense of bittersweet community.” The existence and longevity of legacy servers, which serve to replicate and preserve previous iterations, show that actors may develop attachments to deleted worlds and try to salvage them for as long as possible.

Celia Pearce’s informants lost their virtual world, Uru: Ages Beyond Myst, but instead of entirely giving up on their shared built-then-unbuilt space, they created an “Uru Diaspora” by migrating together to another platform, There.com (https://www.prod.there.com/). In her study, Pearce foregrounds the agency of online actors to preserve their lost world, writing of her ethnography of Uru refugees, “It is the story of the bonds they formed in spite of—indeed because of—this shared trauma, and about their tenacious determination to remain together and to reclaim and reconfigure their own unique group identity and culture.”[30] The initial, and rather abrupt loss of Uru: Ages Beyond Myst in its multiplayer “Uru Prologue” format, in 2004, “had devastated” many of her interlocutors, some of whom reported that it felt “literally like the end of the world.”[31] While Pearce primarily traces the journey of this set of digital refugees to There.com (with some simultaneous play on the SL platform), it will not be surprising that the story of the diaspora was rife with continual change.[32]

Several years after the Uruvian digital refugees had migrated there, in 2010, There.com also shut down (2011). “Old There,” the pre-2010 There, is a no-longer-world. It reopened, altered, a few years later in 2012, and is currently extant as “new There” (https://there.blog/there-com-frequently-asked-questions/). The story Pearce weaves about the Uruvians dealing with successive no-longer-worlds is a fascinating case story detailing the grief that actors can feel when their digital spaces fail.

In thinking about the affective realities of digital ruination, I linger on the ethnographic details collected by Pearce (and incidentally, “co-published” with her avatar alter ego, Artemesia). While collecting stories of the original shutdown of Uru prologue, Pearce learned that some of her collaborators had moved into a close circle to share the end together, so that onscreen it looked as if they were holding hands in solidarity, thus illustrating “virtual world/real grief.” She writes, “Several players recall the clocks in the ‘rl’ (real-life) homes striking midnight, the screen freezing, and a system alert message appearing on the screen: ‘There is something wrong with your internet connection,’ followed by a dialogue box say, ‘OK.’ As one player recalled: ‘I couldn’t bring myself to press that OK button because for me it was NOT OK.’” As she narrates the shutdown of Myst Online: Uru Live (MOUL), which she experienced herself, unlike the loss of Uru Prologue, she notes how “eerie” it was to see the error message signaling that the virtual world had gone offline. Her informants were better prepared this time and more ready to decamp to the digital diaspora, but they still mourned: “During the last days of MOUL, players from around the world gathered in-cavern to say goodbye. Many stayed online to the final moments, staging what some players referred to as a ‘wake.’ European players who could not be online for the shutdown at midnight eastern time parked their avatars in their hoods, watched over by their friends.”[33] As I read Pearce’s work, I cannot help but wonder how the SL actors with whom I have interacted for years would mourn together if the SL platform ever went offline. Make no mistake, their grief would be very, very real.

No-longer-places: Lost Locales in Still Standing Worlds

Where virtual places wholly disappear, they can go with much fanfare or none at all. For my purposes, as a scholar fascinated by the traces—memories, stories, digital fingerprints in other venues, such as on blogs or videos on YouTube—of disappeared places in a still extant virtual world, it is important to differentiate between no-longer-worlds and no-longer-places. A no-longer-place, such as the Bodhi Sim (one of the disappeared SL locales I mentioned earlier) is a location or “build” that is no longer accessible. As I searched out online traces of disappeared Buddhist spaces in SL,[34] I discovered that, by and large, these spaces were very loving and carefully crafted by users—either for love of Buddhism, love of a particular Buddhist teacher or out of hope for political vindication for an exiled leader, such as the Dalai Lama—and they were made to endure. Due to the expense of maintaining builds in SL, however, many Buddhist spaces have folded. The attendant heartache of the creators is sometimes matched by fans of their work, and people who once made a habit of lingering in those now-lost spaces. My work focused on Buddhist spaces and no-longer-spaces, but these lost locales in still persistent worlds is a phenomenon well-known to digital actors in virtual worlds.

In my years of work in the Buddha Center, I talked with many informants who grieved the loss of another, older SL site: the much-celebrated Bodhi Sim. One interlocutor told me that he had first found Buddhism in the Bodhi Sim, or at least that it had spurred a burgeoning interest, and that he missed the pilgrimage spaces the Bodhi Sim had offered. In the midst of interviews, I was sometimes offered links to YouTube videos of the Bodhi Sim in its prime. I also poured through the blogs of the Bodhi Sim’s creator, which are still online, even though the subject is long gone. Of all the no-longer-places I have sought out, the Bodhi Sim is the most widely mourned by the Buddhist practitioners and meditators in SL.

Edits, tweaks and reboots are more common in SL than the closure of places. In the conversations I had with Buddhist builders in SL it became increasingly clear to me that builders might see the space as inherently changeable, even though they generally want the place itself to have a sense of permanence and longevity. Deletions as edits—as builders were upgrading spaces or adding to what was there—were usually fairly unremarkable. At the Buddha Center, there have been many material, physical changes made over time, such as repeatedly replacing Buddhist statues to upgrade to increasingly crisper graphics. As an anthropologist, I have noticed changes in a locale and noticed my interlocutors noticing them; they would often remark to one another about some new aspect of the virtual environment. If these cosmetic changes are the equivalent of redecorating, the wholesale loss of place could feel more like a house burning down.

If a builder chooses to disappear a place in a virtual world like SL, it might have ripples, whether positive or negative, or it might disappear with a whisper. A private space, such as a “private home” in SL that someone maintained, worked on, and constructed for years, may no longer be there when s/he stops paying rent, and this may be cause for personal consternation. However, when shared virtual places that are much beloved are compelled to close—such as when one is beset by unmanageable costs that the builder cannot afford to maintain—builders themselves are more apt to join in the mourning. The builder of the Bodhi Sim, for example, was in step with its admirers in being very clearly unhappy when he deemed it necessary to allow it to slip into the ranks of no-longer-places.

When I returned to SL in 2018 after a few years away, I hoped to visit one of a handful of Buddhist sites that I had once studied. I was shocked that a small lhakhang (Buddhist chapel) dedicated to a Bhutanese lama was gone (Figure 4). I reached out to my interlocutor, “Tornado Alchemy,” who had built it, and he confirmed that it was indeed disappeared, inaccessible (deleted or inventoried— he didn’t recall). I was surprisingly sad that the small lhakhang had joined the ranks of no-longer-places.

I was bereft enough to seek further explanation. Tornado Alchemy explained to me that he had removed the place due to a split with the Bhutanese lama he had once sought to honor with its construction. The builder, in this case, had decided to make his lhakhang a no-longer-place, which meant that it seemed at least as bittersweet to me, an admirer of the space, as it did to the builder himself.

When Tornado Alchemy told me he had moved one special object—a giant prayer wheel with Tibetan mantras inside—away from the disappeared lhakhang and elsewhere to another, still-extant place, I resolved to search it out. When I found the displaced object, I sat my avatar on an outcropping looking down at the giant prayer wheel. I reflected upon the fact that the hunt for the displaced prayer wheel was less a pilgrimage to visit what remained, and more of an opportunity for contemplation, to remember and hold space for what was now gone.

The old Buddha Center had a tea house overlooking the sea where I conducted countless interviews with interlocutors (see Figure 5). The new Buddha Center has a redesigned, upgraded tea house nestled in the woods, but I miss the old one. Perhaps these disappeared places, such as the Bodhi Sim, the Bhutanese chapel, and the old tea house, are small losses in the big picture given how many of these virtual spaces simply wink out of existence every day. A no-longer-place certainly does not compel the affective ripples of a no-longer-world, but when one’s special little piece of a virtual world disappears, it can be a kind of world-ending too.

Digital Archives

All of these types of digital ruination—ruins-by-design, abandonment-of-persistent-places, no-longer-worlds and no-longer-spaces—may or may not be archived or saved somewhere for posterity. Archives become a digital trace when they seek to preserve a virtual space gone dark. For example, the commitment that actors have displayed to their closed virtual builds was on display when, in the aftermath of Yahoo! corporation’s 2009 closure of Geocities, there was a concerted rush of volunteers working together to archive the material.[35]

In Playing with Feelings: Video Games and Affect, Aubrey Anable argues that digital worlds, both in video games and other online spaces, are “affective systems.”[36] In her work, Anable discusses a few case studies in which people confront the changeability of digital worlds head on. One example is the artist Arcangel’s interest in the failures of digital worlds: “For him, failure seems to exist in the gap between our ability to use digital tools as amateurs and how quickly digital technologies and aesthetics seem to become outmoded and ‘bad.’ Planned obsolescence. Programmed to fail. Devices fail, corporations go out of business and stop manufacturing software, and the trends of Internet use shift, as do their aesthetics, leaving closets and landfills full of ‘useless’ devices and hard drives and energy-hungry servers full of outdated files, software, and websites that have not been updated since the 1990s.” In addition, Anable tells readers that New York’s premier museum of modern art, the MoMA, has begun collecting the source codes of early video games for its collection as a means to preserve the design aesthetic of these interactive programs.

Others have begun looking at the archiving of video games, such as the experiment at the Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment (MADE) in Oakland, California, which hopes to preserve online games from being lost. According to Evan Conaway, MADE discourse works to shift the terminology away from “abandonware” and toward “digital heritage,” in order to assert the rights of players to have access to spaces that they have developed attachments to over time (http://blog.castac.org/2018/11/abandoned-game-worlds/). Conaway notes that MADE has logged some progress in archiving old video games, but due to conservative copyright law many games archived with them can only be played alone at the physical museum in Oakland without the benefit of remaining persistent online spaces where people can interact. Thus he concludes that “…they have a long way to go before copyright law is expanded to preserve with abandon what we might call our technological-cultural heritage.”

Audrey Anable sees video games in play as already being “affective archives,” which make its imperative to take the loss of digital worlds over time more seriously. She is correct to note, “All archives, of course, have a close relationship with decay and ruin. And archives are always imperfect and incomplete repositories of objects and ideas.” Yet she asks readers to attend to the way some digital archival work seems to be missing the point—the feelings, for example, that accompany game play and the loss thereof.[37]

Conclusion: Digital Loss

At the end of the movie Blade Runner, as an android named Roy Batty faces his imminent demise, he proclaims—with all the emotion that a fictional AI can muster—the value of digital memories.[38] As his own digital systems fail, Roy haltingly makes his antagonist—the film’s protagonist, Rick Deckard—bear witness to his virtual death, saying, “I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain…” As Roy shuts down, viewers believe him; the moment, although a reprieve for the beleaguered, bloodied Deckard, is surprisingly moving and sad. The implication in the world of Blade Runner, and which echoes throughout this article, is that digital loss can have impactful social meaning and it can also be quite sad.

Ted Nelson, an early programmer and writer, dreamed up and worked upon a hypertext platform, called Xanadu, that sought to serve as an alternative platform to the World Wide Web. As envisioned, Nelson’s platform would have permitted its own kind of “time travel,” as the links and versions of the past would be ever available to be excavated in the present.[39] For example, anthropologist Daniel Rosenberg described the still-unrealized plan thusly: “Xanadu operates as prosthetic memory. It stores everything in alternative versions, and nothing need be lost. A mistaken path can always be retraced, a lost reference recovered, a silenced voice revived…In the world of ideas, texts, and images, versioning is effectively an antidote to linear time. And the design of Xanadu refers to it as such.” Envisioning a virtual world running through Xanadu would mean that nothing would be built-and-then-unbuilt permanently, as one could always go back and access what was: “…electronic writing, as figured by Nelson, energizes a fantasy that death might not be so permanent. Through the chiasmic X of Xanadu, the sands of time pass back and forth: ‘TO UNDO SOMETHING, YOU MERELY GO BACK IN TIME.”[40] Although released in draft form called OpenXanadu in 2014, the project has not (yet) achieved the kind of radically alternative digital experience that Ted Nelson dreams of (https://xanadu.net).

Would the permanent context inherent in Xanadu-like platform make for a less precarious engagement online? Perhaps, but unfortunately, the World Wide Web and the current reality of virtual media do not allow users to access or unbury previous iterations. When worlds and spaces and sites are shut down or deleted, interlocutors sometimes feel this loss keenly. I have sought to delineate some analytical frames for understanding digital ruination and loss, and to show how socially and emotionally significant these disappearances can sometimes be for social actors who have invested in, and sometimes come to love, the virtual places where they spend time.

To return again to the beginning of this piece, please jump backwards and recall with me my exploration of the recently moved and scaled-down Buddha Center in Second Life. In the old Buddha Center, there were two memorial stupas erected for community members who had died in actual life. As I searched the new space, I realized that those two stupas had been merged into one monument to the community’s two lost friends; now the two men’s actual life photos were pasted side-by-side on a wall behind a movable set of sliding doors emblazoned with matching Buddha figures (see Figure 6). I sat my avatar down on a brightly patterned meditation cushion in front of the stupa to reflect on the discomforts of change, a very Buddhist meditation indeed. I reminded myself that although impermanence may be the nature of all things in Buddhism, Buddhists have always cherished their Buddhist places and hoped for their longevity. As I watched the virtual candles in front of the stupa flicker and glow, I felt another surge of gratitude that this digital place still existed in the world.

Suggestions for Further Reading (and Viewing)

Tom Boellstorff. 2008. Coming of Age in Second Life: an Anthropologist Explores the Virtually Human. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Tom Boellstorff, Bonnie Nardi, Celia Pearce, and T.L. Taylor. 2012. Ethnography and Virtual Worlds: A Handbook of Method. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bernhard Drax, dir. 2018. Our Digital Selves: My Avatar is Me. Film. 1 hr 14 min.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GQw02-me0W4. Accessed October 23, 2020.

Jessica Falcone. 2020. “No-longer-places in Virtual Worlds: The Precarity and

Impermanence of Digital Religious Places through a Buddhist Lens.”Journal of the

Japanese Association for Digital Humanities. Vol 5 No 2: 6-41. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jjadh/5/2/5_2/_html/-char/en

T.L Taylor. 2009. Play Between Worlds: Exploring Online Game Culture. First paperback

edition. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Jessica Marie Falcone is Professor of Anthropology at Kansas State University. She is fascinated by transnational Asian religious practices, including Buddhism as practiced in person and online. Her first book, Battling the Buddha of Love: a Cultural Biography of the Greatest Statue Never Built, about a proposed mega-statue project in India, was published by Cornell University Press in 2018. She is currently writing about the in-person (and virtual) Buddhist practices of the community maintaining a 100-year-old Zen temple in Hawai’i. Although no longer a regular Second Life denizen, she is wholeheartedly rooting for the virtual world’s continuing persistence in the digital realm.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to my many interlocutors in Second Life for sharing their perspectives, feelings, beliefs, and stories with me. I am also grateful to the Ethnographic Methods students in my class in Spring 2017 who showed (or kindly feigned) interest in our discussions about the ways anthropologists can study digital culture and digital ruination. Finally, thanks also to Maria Vesperi for her generous editorial work.

Endnotes

[1] Jessica Falcone. 2015. “Our Virtual Materials: The Substance of Buddhist Holy Objects in a Virtual World.” In Buddhism, the Internet and Digital Media: The Pixel in the Lotus, edited by Daniel Veidlinger and Gregory Grieve, 173-190. New York: Routledge.

[2] Jessica Falcone. 2019. “Sacred Realms in Virtual Worlds: The Making of Buddhist Spaces in Second Life.” Critical Research on Religion. Vol 7, No 2.

[3] Jessica Falcone. 2020. “No-longer-places in Virtual Worlds: The Precarity and Impermanence of Digital Religious Places through a Buddhist Lens.”Journal of the Japanese Association for Digital Humanities. Vol 5 No 2: 6-41.

[4] Daniel Terdiman. A Brief history of the Virtual World. Nov. 10, 2006. Cnet. https://www.cnet.com/tech/computing/a-brief-history-of-the-virtual-world/

[5] For example, see Marc A. Smith and Peter Kollock. 1999. Communities in Cyberspace. London: Routledge.

[6] See also Ralph Schroeder. 1996. Possible Worlds: The Social Dynamic of Virtual Reality Technology. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

[7] Jenny Sundén. 2003. Material Virtualities: Approaching Online Textual Embodiment. New York: Peter Lang.

[8] Christoper Helland. 2013. “Ritual.” In Digital Religion: Understanding Religious Practice in New Media Worlds, edited by Heidi A. Campbell.New York: Routledge.

[9] Ken Hillis. 2009. Online a Lot of the Time: Ritual, Fetish, Sign. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

[10] Tom Boellstorff. 2008. Coming of Age in Second Life: an Anthropologist Explores the Virtually Human. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

[11] Anna Tsing. 2005. “How to Make Resources in Order to Destroy Them (and Then Save Them?) on the Salvage Frontier.” In Histories of the Future, edited byRosenberg and Harding, 51-74. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

[12] Dominic Boyer and Cymene Howe. 2018. “Not Ok: a Little Movie about a Small Glacier at the End of the World.” www.notokmovie.com.

[13] Lucas Bessire. 2014. Behold the Black Caiman: a Chronicle of Ayoreo Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[14] Andrew Hoskins. 2013. “The end of decay time.” Memory Studies. Vol 6, No 4, p.388.

[15] Tom Boellstorff, Bonnie Nardi, Celia Pearce, and T.L. Taylor. 2012. Ethnography and Virtual Worlds: A Handbook of Method. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, p.194.

[16] Gregory Price Grieve. 2017. Cyber Zen: Imagining authentic Buddhist Identity, Community, and Practices in the Virtual World of Second Life. New York: Routledge, 166.

[17] For example, this blog post long survived the defunct build it discussed: “Building Potala Palace in a Virtual World.” N.d. Posted by Lily Jun on the blog, Chinese Society and Culture in New Media Art. https://lilyhonglei.wordpress.com/hermit-scholar/building-potala-palace-in-a-virtual-world/ Accessed May 21, 2018.

[18] This essay discussing the Bodhi Sim outlived its source material for several years; while it has now been taken down, for several years it was itself a valuable trace of the no-longer-place: Tenzin Tuque. 2005. “One Tibetan Hermitage, Strip Club Attached.” Posted November 19, 2005. http://milarepalandtrust.blogspot.com. Accessed on October 24, 2010.

[19] Hoskins, “The end of decay time,” p.388.

[20] Laura E. Hall. 2014. “What Happens When Digital Cities Are Abandoned?Exploring the pristine ruins of Second Life and other online spaces.” The Atlantic. July 13.

www.theatlantic.com. Accessed February 20, 2018.

[21] Andrew Reinhard. 2018. Archaeogaming: an Introduction to Archaeology In and Of Video Gaming. New York: Berghahn Books.

[22] Beverly A. Chiarulli, R Scott Moore, Sarah W Neusius, Ben Ford and Marion Smeltzer. 2010. “Public Archaeology in Virtual Worlds.” Anthropology News. September, 35.

[23] Ironically, perhaps, when I searched for these ruins-by-design in SL in 2018, there was no remnant of Archaeology Island left in SL. I found a blog post by the collaborators that indicated they had relocated to a different virtual platform (https://www.iup.edu/news-item.aspx?id=124410). A digital trace allowed me a substantive look at the virtual space that had been removed from SL: at the time of writing a tour of SL’s Archaeology Island was only extant on YouTube (“A Walk Through the IUP Virtual Archaeology Island” – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UurS5LzoJMI. Thus, the SL “ruins” of Archaeology Island are now lost—a no-longer-place—but for a time it was an extant place of ruins-by-design.

[24] Hall, “What Happens When Digital Cities Are Abandoned?”

[25] Jason Johnson. 2018. “’Minecraft’ Data Mining Reveals Players’ Darkest Secrets: A Minecraft fan is using data-mining techniques to retrieve players’ in-game journals and correspondence, some of which is inspiring, depressing, and absurd.” Motherboard. February 9. www.motherboard.vice.com. Accessed March 18, 2018.

[26] Reinhard, Archaeogaming, p.158.

[27] Hoskins, “The end of decay time,” p. 388.

[28] Evan P. Conaway. n.d. Abandonware and the Preservation of Online Games. AAA Conference Paper. San Jose, CA. 2018.

[29] Hillis, Online a Lot of the Time.

[30] Celia Pearce and Artemesia. 2011. Communities of Play: Emergent Cultures in Multiplayer Games and Virtual Worlds. First paperback edition. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 6-7.

[31] Pearce and Artemesia, Communities of Play, 268-9.

[32] Here a few other examples of turmoil and change faced by the refugees Pearce (2011) studied: 1) a few years after closing “Uru Prologue,” the corporation relaunched as Myst Online: Uru Live (MOUL) in 2007, and actively tapped into the digital diaspora to lure players into the new platform; 2) the Second Life build of the Uru diaspora, “D’ni Island” winked out due to the expense of maintaining the build; 3) just over a year after opening, MOUL closed, again sending Uruvians off to their digital diaspora.

[33] Pearce and Artemesia, Communities of Play, pp. 88, 88-89, 269, 268.

[34] Falcone, “No-longer-places in Virtual Worlds.”

[35] Hall, “What Happens When Digital Cities Are Abandoned?”

[36]Aubrey Anable. 2018. Playing With Feelings: Video Games and Affect. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p.125.

[37] Anable, Playing With Feelings, p.133-4.

[38] Ridley Scott. dir. Blade Runner. 1982. Distributed by Warner Bros. DVD

[39] Daniel Rosenberg. 2005. “Electronic Memory.” In Histories of the Future, edited by Daniel Rosenberg and Susan Harding. Durham, NC: Duke University Press: 123-152.

[40] Rosenberg, “Electronic Memory,” p.137, 138.