George Kunnath

To cite this article: George Kunnath (2020) Doni the Anthropologist’s Dog: A Scent of Ethnographic Fieldwork, Anthropology Now, 12:3, 106-121, DOI: 10.1080/19428200.2020.1884482

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/19428200.2020.1884482

Doni the anthropologist’s dog—this is how he came to be known in Krantipur, a forested region in the state of Jharkhand in eastern India. Doni started accompanying the anthropologist when he was still a puppy. Both were sniffing out information, although of rather different types. The anthropologist was mainly interested in the ongoing Maoist insurgency and counterinsurgency in Krantipur and its surroundings. Doni, a keen observer himself, had a much wider range of interests. He was interested in the anthropologist, the people with whom he interacted, strangers who passed by the village, children who played around the mud houses munching snacks; in other dogs, cows, goats, chickens; in food shops; the local bazaar and all sorts of sounds and smells. He was always excited about the “field trips” with the anthropologist, enjoying the attention and the occasional treats he received during these outings.

Doni was not one of those prestigious pedigreed dogs such as the Corgi, Jack Russell, Spaniel, Labrador, Doberman and numerous other “purebreds.” He was not even a mongrel or mutt, the so-called mixed breed. Doni was of humble origins. He was a pariah dog, a member of a “primitive” or “indigenous” breed, which makes up the largest dog population in India. The lives of the pariah are pre- carious; they exist mostly as strays, scavenging on humans’ leftovers and garbage. And it is because of their marginal existence that the British colonialists named them the “pariah” (outcast), a term pejoratively used to refer to an “untouchable” community in South India. Just like this Pariah caste, Doni’s dog family is derided and ill-treated by most people, no matter to which caste or class they belong.

Then why should the story of Doni, a stray dog, matter at all? Well, he might have been a pariah, but Doni was also an anthropologist in his own right. Like dogs of any breed, Doni possessed all the abilities that made him a virtuoso interpreter of human behavior. The greatest of these abilities was his sense of smell. Compared with humans, who have around 6 million olfactory receptors, Doni possessed more than 200 million sensors in his nostrils. His powerful sense of smell enabled him to interpret the world around him in unique ways. He could smell, for example, various human emotions—joy, sadness, fear, anger, anxiety, trust, love. When experiencing a particular emotion, a human body re- leases pheromones, and Doni could perceive these chemicals and identify an emotion associated with them. His olfactory knowledge was further enhanced by his sight and hearing. He was acutely alert to the tone of human voices, their movements, routines, food habits, interactions and way of life. Doni was born with all these abilities, and he developed them further as he matured into adulthood during the two years when he was the anthropologist’s companion.

But it is not just his remarkable abilities in interpreting human behavior that make Doni’s story special, as he shared these with other dogs. The objects and the circumstances of Doni’s observations were unusual. Doni and his anthropologist lived in a theatre of war, in the midst of the ongoing Maoist insurgency and counterinsurgency. Doni’s story reflects his own experience of violence and his observations of how violence affected others around him. Doni’s story has yet another dimension: his rise from a lowly stray to fame as the anthropologist’s dog and his fall once the anthropologist left the field highlight the relations between power and knowledge in the field, and the ways the authority of an anthropologist can affect those associated with him, be they humans or nonhumans. Finally, Doni’s story is a humble reminder of all those nonhuman “others” who are ever present in anthropological research yet rarely make it from the field onto the pages of books and articles, except as numbers or blurry figures in the description of a fieldwork site.

Dognapped

Doni’s story began with a nightmarish encounter on a rainy afternoon in August 2008. A two-month-old puppy, he was chasing a herd of monkeys with his mother in the forests of Krantipur when an elderly man ambushed them. The man’s intention was clear: he wanted to capture Doni. The man kept throwing stones at Doni’s mother to chase her away. She barked as though urging Doni to run, and run he did. But in that frantic run he fell into a ditch, and it was only a few moments before the man trapped him into a big bag and carried him away. Doni had no idea where he was being taken. He was terrified and kept whining. He did not know how long it had been when finally the man stopped and put the bag down. But before letting Doni out, he put a leash around his little neck. He then tied him to a wooden post outside a house. Doni howled and moaned! An elderly woman and a few village children gathered around and jeered. The man put a bowl of rice in front of Doni, but Doni felt no hunger, only fear. He kept crying out for his mother, whom he would never see again. Eventually, still terrified and tired, he closed his eyes.

As night approached, the anthropologist arrived. He called Doni’s capturer Baba and his wife Ayo, the terms for father and mother in Kurukh, a language spoken by the Oraon tribe. Doni, who was familiar with the sound and tone of the languages spoken by various ethnic communities in Krantipur, at once realized that the anthropologist was an outsider. He became more terrified, having no idea what to expect from this stranger. In Doni’s region, people had to take care of so many things, toiling from dawn to dusk in either the agricultural fields or the forest. They had little care to spare on stray dogs. If dogs were lucky, some households would occasionally put out leftover food, but mostly they survived on scavenging human rubbish. They learned to coexist with the local humans without much expectation, even tolerating ill treatment.

But strangers were different; they posed grave threats. Doni had seen policemen, who were outsiders, beating dogs for barking at them on their village patrols. Now with the anthropologist leaning over him, Doni’s nostrils quivered, straining to gather as much information as this stranger’s scent would provide. Doni could sense no hostility in the newcomer, however, only concern and sympathy. Yet when the anthropologist sat down beside him and started patting him, Doni was confused. A part of him longed to curl up to him, lick his hand and express that inborn canine quality of trust and loyalty. Yet the harsh lessons learned from experience and his mother’s advice reminded him to be cautious with humans. While Doni was struggling over his doubts, the anthropologist was speaking with Baba and Ayo. He could hear the word Doni mentioned often. And, when the anthropologist started to use the word “Doni” to call him, he realized that Doni was his name. His mother never gave him a name; she never needed one to call him or pamper him. Other strays in the locality recognized him by his smell and color. Being called Doni seemed strange at first, but soon he learned to respond to this sound, and a few weeks later he would become famous in Krantipur as Doni the anthropologist’s dog! But naming was only the beginning…

Despite the reassuring gestures from the anthropologist, Doni still looked intimidated when he was taken into the room where the anthropologist stayed. This was the first time Doni had ever entered a human house. The anthropologist spread an old sack in one corner of the room, making a bed for Doni. The unfamiliarity of all this was unsettling; Doni was more scared than excited by these “privileges.” He only wished for the comforting company of his mother, and kept whimpering through the night. Next morning the anthropologist was up early. Before leaving the house, he tied Doni to the same wooden post outside the house and gave him food and water. But Doni wanted to follow him and cried out after him. Although the anthropologist turned back to give a reassuring look, he walked away and did not return until the evening. During that day, Doni kept whining, whimpering and growling. He tried to break the leash by biting it. Children from the neighboring houses gathered around him, laughing at his futile attempts to escape. But at least none of them threw stones at him. In the evening when the anthropologist returned, Doni jumped up toward him with joy, wagging his tail and making low-pitched moans. And as the anthropologist sat near him, he nose-nudged him to show his affection. Doni rolled over, allowing the anthropologist to belly-tickle him. A new friendship was being formed.

After two days of agony on the leash, Doni was freed so that he could accompany the anthropologist, first in the village where they stayed and later in the neighboring villages and the local bazaar. The anthropologist was new to Krantipur; he had arrived just a couple weeks before that fateful afternoon of Doni’s abduction. But word had already spread in the area that a researcher from the city had come to study the everyday life of the villagers amidst the armed violence between Maoist guerrillas and state security forces. During the early days of their field visits, Doni could sense suspicion among villagers and their hesitancy in the presence of the anthropologist. His supersensitive snout sensed the villagers’ emotions, fear being the dominant one. The anthropologist was also aware of their hesitancy but could do little to encourage them to talk. Doni could sense the anthropologist’s helplessness, too. Doni did what dogs do in situations of impasse among themselves; he let out friendly barks and rolled on the ground. This was something he had seen his mother doing when uneasiness and tensions flared up among members of her dog pack. Doni’s antics seemed to lighten the situation, leading to freer interactions between the anthropologist and the villagers. People liked asking questions about Doni first, and then they would gradually open up and talk about themselves. Doni’s anthropological skills were thus on display: he helped his anthropologist friend to build rapport with the people in the field.

People in Krantipur seemed fascinated by Doni, perhaps because of the novelty of the unusual friendship: a stray dog had become a companion of the researcher from the city! Perhaps some of the interest was due to the name Doni, which they tended to associate with that of a famous Indian sportsperson despite the difference in pronunciation and spelling. Doni gradually became famous as Doni the anthropologist’s dog. His anthropologist companion enjoyed a position of power and prestige, probably because he was seen as an educated city dweller conducting research among the rural poor. Now even the anthropologist’s dog seemed to share in that privilege. And what a privilege it was! During their visits to the local tea stall, Doni was allowed to enter the shop and lie down under the table when the anthropologist was having his samosa and tea. The tea stall man would often offer Doni jalebi and biscuits while he would beat and chase away all other dogs that would come anywhere near his tea stall. For the moment, Doni seemed to enjoy all the perks. Some people referred to him as sir ji ka kutta (sir’s dog). For some others, he became comrade ka kutta; “comrade” was a widely used term in Krantipur because of the strong presence of Maoist guerrillas in the region.

Into the Camp

Doni’s adventurous streak once led him straight into the Maoist camp. He quietly followed the members of a Local Organization Squad (LOS), who were heading to the forest camp after a visit to villages. Doni had become used to the LOS members when they were organizing various activities in his village, and especially when they ate food at Baba and Ayo’s house, as they always gave him a portion. The LOS members noticed only Doni when they had trekked deep into the forest. They recognized him as comrade ka kutta. Being deep in the forest with dusk falling, they did not want to send him back to the village, so they allowed him to follow them. It was early October, the safest period for the guerrillas, as the dense foliage after the monsoon gave good cover for setting up their camps. Moreover, the swollen rivers made it difficult for the security forces to venture into their area. The Maoists used this period to hold large meetings and training sessions. When Doni and his LOS companions arrived at the camp, it was already dark. But long before the guards became aware of the approaching group, four dogs ran toward them barking. They knew the LOS members, so their target was Doni. They sur- rounded him with their tails up and hackles raised. Doni curled up with his tail tucked in, sending out signals of respect and nonaggression. The leader of the LOS called out to the dogs, asserting that Doni was not a stranger but part of their group, and he was comrade ka kutta. Three of the attacking pack looked at their leader, an alpha female, for guidance. Doni noticed her slight turn of head and understood that he has been accepted.

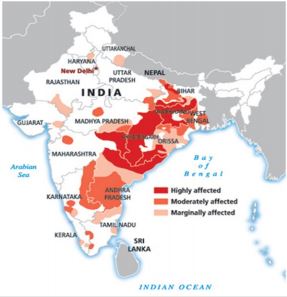

The Maoist movement in India started with the peasant revolt in Naxalbari village in West Bengal in 1967; hence it is also called the Naxalite movement. The movement aims to establish a Communist state through an armed revolution. It has a strong presence in several Indian states, especially in Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Bengal, Bihar and Jharkhand. Krantipur, known as the “Red Capital,” has been a strong Maoist guerrilla zone in the state of Jharkhand. The guerrillas first entered its forest villages from the plains of Central Bihar in the 1990s.

They drove out the forest guards who exploited the local Adivasi or Indigenous populations and established Krantipur as their guerrilla zone, with the intention of turning this region into a “liberated area” from the control of the Indian state. The Local Organization Squad (LOS), consisting of around 12 to 15 guerrillas, was the smallest unit entrusted with the task of mass mobilization and grassroots work in this region. Each LOS covered eight to 12 villages, and three operated in Krantipur region. They organized village meetings and protest marches against police atrocities, price rises, mining projects and inadequate health care and education. They assisted in the formation and functioning of various village organizations run by the Maoists such as judicial, peasant, cultural, forest, sports, workers’ and women’s committees. The LOSs also provided logistics support to the larger Maoist formations for conducting guerrilla conferences and training sessions in the forests of Krantipur.

Doni would later learn that her name was Kranti. Maoist guerrillas followed their own logic in naming dogs. Sometimes the names they chose reflected their political ideology, and sometimes they were based on certain predominant characteristics displayed by a dog or simply on a dog’s own background. Kranti means revolution. Other dogs were Lal Suraj (red sun), and Layla and Majnun, named after the two protagonists in a famous love story. Layla and Majnun, Doni noticed, were nursing grievous injuries. Doni was grateful to his new companions, and he demonstrated it by incessantly wagging his tail and licking the faces of the other four dogs. As Doni’s LOS companions entered the camp, they were welcomed by an endless line of comrades with a greeting of Lal Salam (red salute)—a raised clenched fist, followed by a firm handshake. Every- one in Krantipur knew this greeting ritual, and Doni had seen it performed whenever the guerrillas visited his village. His canine comrades now moved around excitedly, barking their version of Lal Salam. Doni sensed an air of strength and confidence as the guerrillas stood in a line and greeted one another, assault rifles hung over their shoulders. When these same men and women visited the villages, they were always on high alert, as though they were expecting an ambush or attack at any moment, just like Doni’s stray family was always looking over their shoulders to avoid stones thrown at them. But in this camp, the guerrillas and their dogs seemed to send out a feeling of invincibility. Deep in the forest, they were their own masters.

After a quick dal-roti supper with his LOS companions, Doni settled by the hearth beside his new canine comrades. Like all dogs, Doni was inquisitive about his new friends. He learned that Kranti had been living with the Maoist guerrillas for more than five years. She was born in the camp. Soon after her birth, her parents were shot dead by the police when the dogs charged at them during an encounter between the Maoists and the security forces. The guerrillas then became her only family. She had taken part in many of their fierce encounters with the security forces and criminal gangs. When the Maoists prepared an ambush, she remained completely silent; when they charged, she charged with them. When they moved through the forests, she always walked in front, alerting them of any dangers—from police to poisonous snakes. Kranti had become a legend among the Maoist cadres in Krantipur.

Lal Suraj, Doni learned, had come to the camp one year ago. Before that he lived as a stray in Krantipur bazaar, often getting thrashed by the tea stall owners for nicking a samosa or jalebi that was tantalisingly displayed at a shop front. In early 2008, during an anti-Maoist operation, the police set up a security camp in the local school. One night the Maoists fired at the police camp. Although there were no casualties, the next morning the police brutally assaulted the local people for allegedly supporting the rebels. They entered every house, dragged out men, women and elderly people and severely beat them. After that incident, Krantipur bazaar was never the same again. Shopkeepers were frightened to open their shops, and many people left their homes. Those who stayed feared that the police would shoot everyone. Lal Suraj could smell fear in every human, young and old. One night, a week after the incident, a Maoist platoon arrived in the bazaar to reassure the people. Strangely, Lal Suraj sensed no fear in them, only a strong odor of defiance. At that moment Lal Suraj decided to follow the Maoists into the forest. At the camp, for the first time in his life, he was not despised but felt respected, and he stayed.

The story of Layla and Majnun was more harrowing, and they had taken shelter in the camp just a few days before Doni’s visit. Beaten and chased out of a village by a group of unruly children for displaying their love in public, they came to the camp and were welcomed. They were still recovering from their injuries and trauma, and Kranti, Lal Suraj and the human comrades were caring for them.

Shortly before midnight, Kranti and Lal Suraj left to accompany the comrades on guard duty. Doni dozed off, lying beside Layla and Majnun, and he had a dream. Not every dog dream is about chasing rabbits. Doni dreamed of a place where dogs are not abused but respected for their qualities and services; he dreamed of a place where dogs could work together with humans to create a more caring world.

The morning started with the roll call and physical training. Doni went to the training grounds with Kranti, Lal Suraj and the human comrades. The exercise regime included running, piggybacking, push-ups, sit-ups and the like. Then everyone headed straight to the breakfast stall under a tree, and Doni also got his portion. He loved that breakfast of chapati and chickpea curry! Next in the routine was a two-hour study time. Human comrades studied the revolutionary ideas of Marx, Lenin and Mao and the documents of the Maoist party. Those who could not read or write were taught literacy by other comrades.

While the human comrades were busy studying, Doni went with Kranti and Lal Suraj around the camp. Their canine noses first led them to the kitchen where lunch was being prepared. Four comrades were cooking rice and vegetables; some of them were men. In the village households, Doni had seen only women doing the cooking. He learned that in the camps, people followed a weekly rotation by which both men and women shared cooking, cleaning and other chores. Close to the cooking area, food items were neatly stacked: sacks of rice, dal, potatoes, onions and a basket of green chillies—an essential item for all meals—but Doni and his canine companions had little interest. Their next stop was the sleeping quarters. There were five tents—four for men and one for women—each allowing for 10 to 15 comrades to sleep comfortably on the floor. There might have been more than 50 guerrillas in this camp—around 40 men and 10 women. At night, Doni would see them sleeping in their uniforms with shoes and guns nearby, always battle-ready!

Just before noon, all the comrades headed to the nearby river for bathing, another essential daily routine, Doni learned. After that it was lunchtime. This day it was rice, dal and green chilli. While the human comrades ate, one person from the kitchen committee served the canine comrades. The food was delicious! Doni finished his meal quickly and then looked around. He noticed that the human comrades ate in groups of three or four, each group eating from the same plate. That was new. In his village, he had seen a man and his children or a woman and her children eating from the same plate, but he had never seen grown-ups eating from the same plate. Again, Doni turned to Kranti and Lal Suraj, and learned that this was another custom followed in the camp. As many of the human comrades hailed from different castes and tribes, sharing meals was a way of eliminating any notions of hierarchy based on purity and pollution or family backgrounds, and of creating a new comrades, family.

After the lunch, the human comrades who were not on guard duty took a short nap, some in the sleeping tents and others under the shades of trees. Doni and his friends took a nap under a tree as well. Then it was again time for classes and meetings. In the evening, everyone was back at the training grounds. An experienced comrade guided the group through the drills of engaging enemy forces and staging ambushes. Kranti and Lal Suraj took part in these exercises. They ran excitedly as the human comrades staged various formations of attack and retreat. Doni stood by the side and admired them; his canine comrades had learned to work with humans as a team. Was it their shared experience

of being “outcasts” that made their bond so strong in this unlikely place—the deep jungles of Krantipur? Doni also felt a sense of belonging to their group; after all, he too had experienced ill treatment and suffering before he met the anthropologist.

Later in the evening, the exquisite aroma from the kitchen brought huge excitement among the comrades, both human and ca- nine. There was mutton for dinner! Doni learned that the human comrades had bought a goat from a farmer in a nearby village. It was a great mutton feast, which Doni really enjoyed, feeling almost as if it were held in his honor. Doni heard the camp commander asking who the new dog was, pointing toward him. One of the people whom Doni had followed into the camp on the previous day replied that he was the anthropologist’s dog. Concerned that the anthropologist might be worried about his missing dog, the commander asked two comrades to take Doni back to the village first thing in the morning. In the midst of all the excitement at the camp, Doni had forgotten about the anthropologist!

Next morning, Doni bade farewell to everyone with a powerful bark of Lal Salam. He licked the faces of his canine comrades and wished Layla and Majnun a speedy recovery. Accompanied by two human comrades with guns, he returned to the village. As they were approaching the boundary of the village, the news spread that Doni was back with body- guards. The anthropologist and Baba came running to greet Doni. Even Ayo, who generally seemed cold toward him, came with a bowl of rice, saying that he might have been starving in the forest. Doni enjoyed all the attention and adulation, which kept growing in the company of the anthropologist. He greeted the anthropologist by jumping all over him and kept whimpering and rolling on the grass with the sheer joy of meeting his friend.

Return, Separation and a New Beginning

Months had passed since Doni returned from the camp, but the memories of that place, of Kranti and Lal Suraj, were kept refreshed by the LOS members’ frequent visits to the village. Each time they arrived, Doni would run to them and greet them with friendly barks of Lal Salam and enthusiastic tail-wagging. They responded warmly by sharing their food with him. Doni’s friendliness with the LOS gave the anthropologist an opportunity to interact with the guerrillas, to ask questions and listen to the stories of these men and women who had joined the Maoist ranks. Doni thus became the facilitator of anthological research on the Maoist guerrillas.

The anthropologist noticed that ever since returning from the camp, Doni had become more vocal and bolder. Before, when Doni accompanied the anthropologist to the tea stall, he would sit quietly by the anthropologist’s side, humbly waiting for the goodies the shopkeeper would give him. To repay, he even assisted the shopkeeper in chasing away other strays that came near the shop by barking at them. But now, to everyone’s surprise, Doni snarled at the shopkeeper when he tried to disperse the strays with his stick. Experiences at the camp seemed to have changed Doni, as if he had acquired a new feeling of comradery for the strays ill-treated and abused by humans.

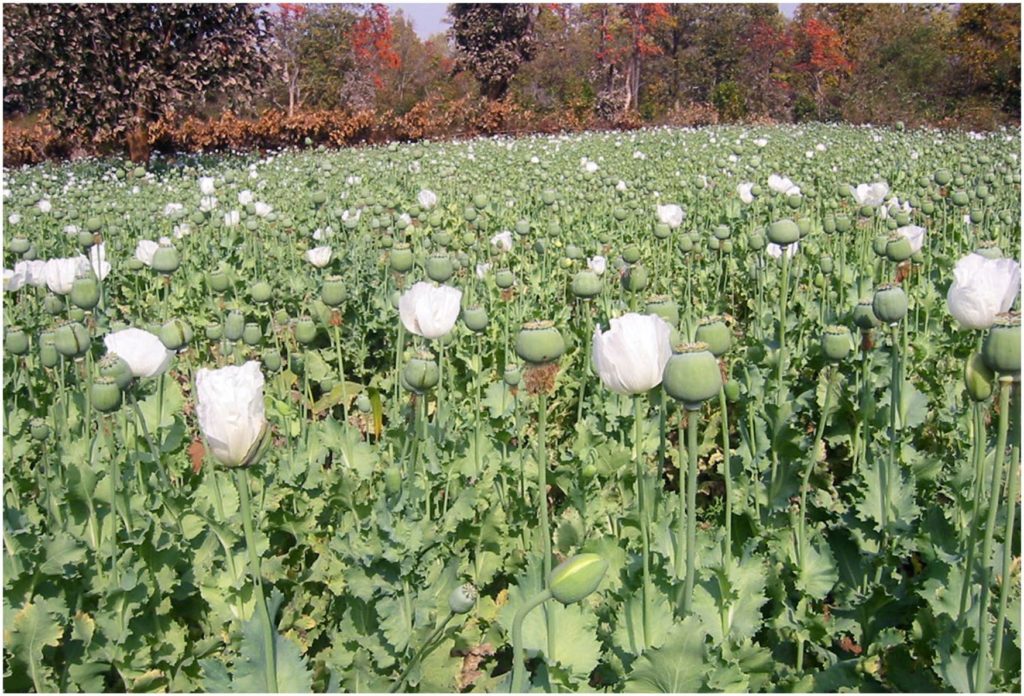

Doni continued to employ his sensory abilities in various ways. One morning when he and the anthropologist were going to a village in the middle of the forest, Doni seemed to pick up an unfamiliar smell. He flared his nostrils, allowing as much air as possible to enter the upper part of his snout, but still seemed to struggle to make sense of it. Being naturally curious, he ran toward the source of the scent. After a while, when Doni had not returned, the anthropologist went looking for him and saw for himself the source of the smell. In the opening in the forest, there was a large field of opium poppies, almost ready for harvest. The anthropologist learned that someone from the city was using the local farmers to cultivate opium for profit. Doni and the anthropologist went straight to the senior Maoist leader in Krantipur. It seemed the Maoist leader had been unaware of the introduction of opium cultivation nearby. Due to Doni’s and the anthropologist’s intervention, the leader took immediate action. He sent the LOS to the site, and the opium poppies were slashed and burned. He also instructed the farmers involved not to cultivate opium poppies again. The word spread in Krantipur, and Doni’s popularity soared.

Doni excelled in teamwork with the anthropologist. He seemed to display a more keen awareness of human/nonhuman interaction than the anthropologist himself. For his human companion, the interactions between people and animals remained an un- explored area, despite Doni’s own strong presence in his fieldwork. The anthropologist was solely focused on understanding the everyday life of humans amidst violence. He paid little attention to how their lifeworld was in fact shaped by their relations with nonhuman beings—cows, goats, dogs, chickens and various other animals. His anthropological perspective on the everyday life in Krantipur would have benefitted from being a little more inclusive.

In March 2010, their fieldwork ended. Twenty months had passed quickly, and it was time for a farewell. Doni could sense the sadness. The anthropologist was feeling sad to leave his Baba, Ayo, the villagers, the comrades and especially Doni, his fieldwork companion for all these months. In Krantipur, there was also a growing anxiety and fear among all. The effect of the state’s ruthless crackdown on the Maoist movement was being felt in the forest villages. The security forces were gradually closing in on Krantipur from all sides. More police camps were being built, and thousands of troops moved into the forest areas. Fear was growing all over the place. The villagers were being stopped, searched, arrested and tortured for their association with the guerrillas, imagined or real. Doni could sense the fear all around him; he seemed restless. Waiting for the shared jeep that took people from the village to the nearby town and beyond, the anthropologist hugged Doni, who noticed tears in the anthropologist’s eyes. Doni began to nose-nudge him and lick his face. When the anthropologist finally got into the jeep and the vehicle moved, leaving Doni behind on the dusty road, Doni’s heart broke. He ran after the vehicle as far as he could, barking. But eventually, his legs gave way and he stopped. He was left standing in the middle of the road, alone, inconsolable.

When Doni returned to the village after several hours, Baba and Ayo tried to console him. They gave him extra rice and dal that day, and everyone in the village expressed their sympathy. But as the days passed, no one seemed to care about a sad and abandoned dog. Even Baba and Ayo had other concerns. Doni went to the bazaar, hoping the tea stall owner would recognize him and give him his favorite jalebi and biscuits. But he treated Doni just as he treated other strays, chasing him away with his long stick. Children threw stones at him. Those who once seemed fascinated by Doni the anthropologist’s dog paid no attention to him anymore. Eventually Baba and Ayo closed the anthropologist’s room, and Doni was no longer allowed to sleep on the little bed that the anthropologist had made for him in the corner on the first evening of their encounter. He once again became a pariah, unwanted and uncared for. Humiliated and heartbroken, Doni began to confine himself to the backyard of the house, away from all the jeering eyes. Their fieldwork became just a memory, the sooner forgotten the better.

Yet, when he closed his eyes, the images of the Maoist camp flashed through Doni’s mind—Kranti and Lal Suraj, respected not for their breed or powerful friends but for their qualities and actions, taking part in the exercises at the training grounds . . . Layla and Majnun nursing their wounds and being cared for . . . Human comrades eating from the same plate . . . Men and women cooking, cleaning and fighting by each other’s side . . .

Doni stood up and began walking, leaving behind his backyard, Baba’s house, their village, running towards the forest, faster and faster . . . As he approached the forest, a powerful bark emerged from deep within himself—Lal Salam!

Afterword

It was a year before I could return to Krantipur. Back in my old village, I called out for Doni, but he was no longer there. Baba told me that after I left, Doni became withdrawn and refused to eat. One day he just vanished. “Most probably he was snatched by a leopard,” Baba said. At that time, there were many reports of goats being eaten by a leopard that strayed into the village. I asked if Baba saw any signs of Doni’s blood or his remains in the nearby forest. He said nothing was found.

Baba added it was also possible that Doni went away with the Maoists. Some villagers, he said, had seen him “guiding” a Maoist squad on the forest path. A few days later, I met a couple of Adivasi women who also told me that they had seen Doni near a Maoist camp playing with other dogs. I recalled how after his visit to the Maoist camp, Doni would get excited every time the guerrillas visited our village; I remembered the drastic changes in him, his bold and vocal interventions. As I dwelt on these memories, I grew more and more convinced that Doni did not die of a broken heart or get snatched by a leopard. Instead, it became clear to me that Doni had joined Kranti, Lal Suraj, Layla and Majnun and his many human comrades in their search for respect and a new purpose, together.

Acknowledgments

I extend my special thanks to Barbara Harriss- White, Jenny O’Brien and Alena Kulinich for their helpful comments on the initial draft of this article. I also thank the editorial team at Anthropology Now, especially Maria Vesperi, Sydney Silverstein and Ry- lan Higgins, for all their help. I am grateful to Doni for the fieldwork assistance and the fond memories.

George Kunnath is a social anthropologist and a research fellow at the International Inequalities Institute, London School of Economics and Political Science. He is also a research associate at the Oxford School of Global and Area Studies, University of Oxford. His research explores the relationality of poverty, conflict and development in the context of the Maoist insurgency and counterinsurgency in India. He is also engaged in comparative research on armed conflicts and peace processes, focusing on the FARC in Colombia and the Maoist movement in India. Kunnath has published his research in Current Anthropology, Journal of Peasant Studies, and Dialectical Anthropology, among others. His book Rebels from the Mud Houses: Dalits and the Making of the Maoist Revolution in Bihar (Social Science Press, 2012; Routledge, 2017) discusses Dalit resistance, Maoist movement and caste and class relations in the eastern Indian state of Bihar.