===In response to the terrible devastation in Haiti, Anthropology Now is offering special coverage of events in Haiti. For the next few weeks, Press Watch will be a dedicated Haiti Watch. Elizabeth Chin, a professor of anthropology at Occidental College who has worked for many years in Haiti joins us as a Featured Special Report guest blogger.For her previous posts, Click on ‘Read More’ in Press Watch. We will also be tracking news coverage of anthropologist Paul Farmer and his work on the relief efforts. And we encourage all concerned readers to donate generously to Partners in Health, the organization Paul Farmer co-founded that is working on the ground in Haiti. Please contact us with links and news on Haiti that we can share with our readers.===

*Special Report blogger Elizabeth Chin is an anthropologist who has studied Haitian Folklore dance for over 20 years, both in the US and in Haiti. Currently a professor at Occidental College, she has been spending time in Haiti since 1993, sometimes doing fieldwork and sometimes not. She will return to Haiti in May to assist with the relief effort.*

Like anything having to do with Vodou — or Haiti for that matter — the songs song by Vodouisants are rich with multiple layers of meaning. Pat Robertson’s vile and mean spirited remarks about Haiti having a pact with the devil (as if that would explain an earthquake 200 years after the revolution) have been dealt with handily by the likes of Elizabeth McAlister, who knows a great deal about Haitian music and culture, and by Gina Ulysse.

Here’s something from Liza: http://interfaithradio.org/node/1218

Here’s something from Gina: http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=122567412

The Vodou songs are incredibly dense pieces of history and culture and life and emotion. “Manman Mwen,” which you can hear being heard by Pierre Cheriza for a mere .99 cent download from itunes, goes like this:

my rough translation:

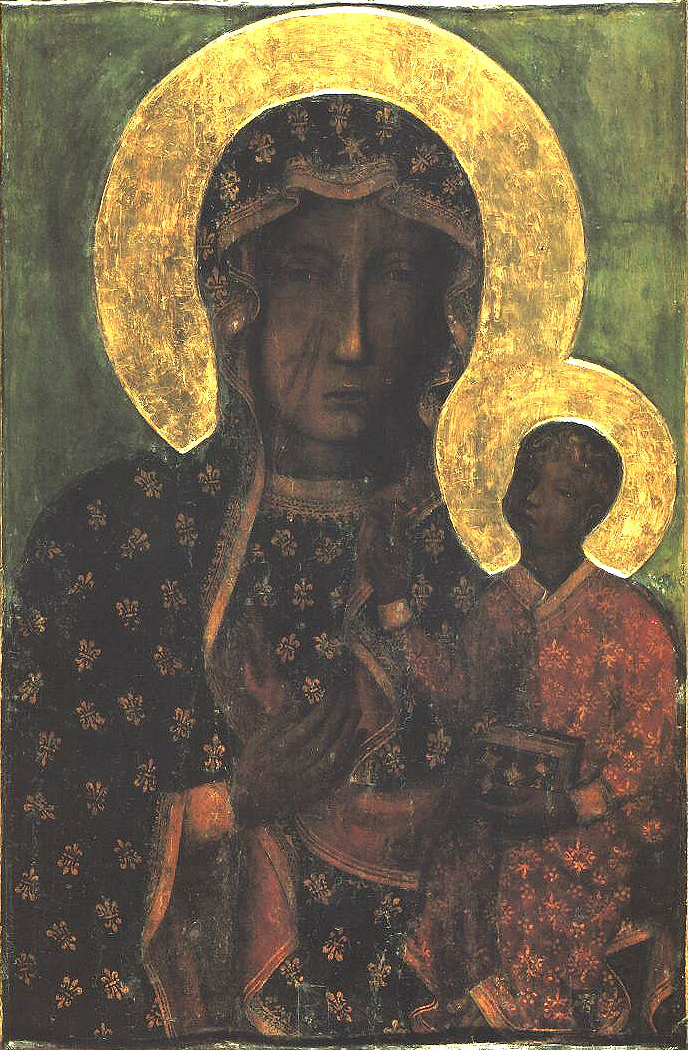

But the song is ever so much deeper than it might appear. It is being sung to Erzulie Dantor, the fierce mother, the dark-skinned woman who is represented in Christian iconography as the Black Madonna of Czestochowa. She’s serious and dour looking, holding her son in her arms, her cheek bearing two long gashes still weeping blood. This is a woman who will fight to the death to protect her children. Her symbol is a heart with a knife through it. She doesn’t play around and she doesn’t tolerate betrayal. But if she’s so strong and protective, how come in the song her children sound so lost, so afraid?

Her children are calling to her, and the song is heart-breakingly sad. I always think of abandoned children when I hear it, children calling out desperately for their mother to come to them, frightened and alone. “Mother, O mother where are you?” the song says, over and over and over. Well, that sense of abandonment comes from many quarters — the people who had been snatched up and thrown on ships, for instance, probably felt the need to cry out in just this way, and thinking of those ships crossing the wide, wide waters of the Atlantic, unimaginably wide, one can imagine why ‘waiting in the water’ was terrifying.

But water has many other meanings and uses, and often in Vodou rituals people stand in sacred pools, under waterfalls, or pour water on themselves as purification and spiritual renewal. So this also speaks of an expectant group of devotees, standing perhaps in one such sacred pool, eagerly awaiting Erzulie’s arrival. They cajole — “Pwoche lakay o” — come into the house! Perhaps they are joyful, saying come into the house, we are ready for you! Perhaps they are cold and miserable and want their mother to return to them to enfold them in her arms, and cast her baleful stare upon anyone who might dare to harm her precious children.

Erzulie’s rage, and Erzulie’s passion are surely big enough to take on the work of avenging all of her children now suffering in Haiti. Let’s hope her knife doesn’t come flashing in our direction, because we have inflicted much that is worthy of regret, much that requires atonement on an epic scale.