To cite this article: Amy Moran-Thomas (2021) Notes from a Fever Dream, Anthropology Now, 13:1, 11-24, DOI: 10.1080/19428200.2021.1903487

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/19428200.2021.1903487

Amy Moran-Thomas

I spent much of last May watching my husband try to breathe. Sitting up on the living room floor with coffee as he fell asleep on our couch, I had promised to watch his oxygen numbers. The blue numbers flickered in and out as I tried to stay awake. Almost every night, it was the same pattern. While he was awake, they would hover just above 92, the threshold for going to the ER. When he fell asleep, they would begin to tumble further. I was supposed to wake him up if the oximeter read below 88. On the scariest nights, his numbers crashed into the 70s, the levels when damage can occur to vital organs such as the heart and brain. His doctor suspected the virus could be distorting the signals that the brain sends to the lungs to keep breathing during sleep.

Doctors are still debating why Covid simulates certain aspects of altitude. But it was the image in my mind when I watch the oxygen numbers plunge, as if he was lifting off in an airplane. The device’s measures were first invented for climbers, astronauts and pilots. The lower readings on our meter’s screen were associated with oxygen levels experienced at altitudes above 8,000 feet.

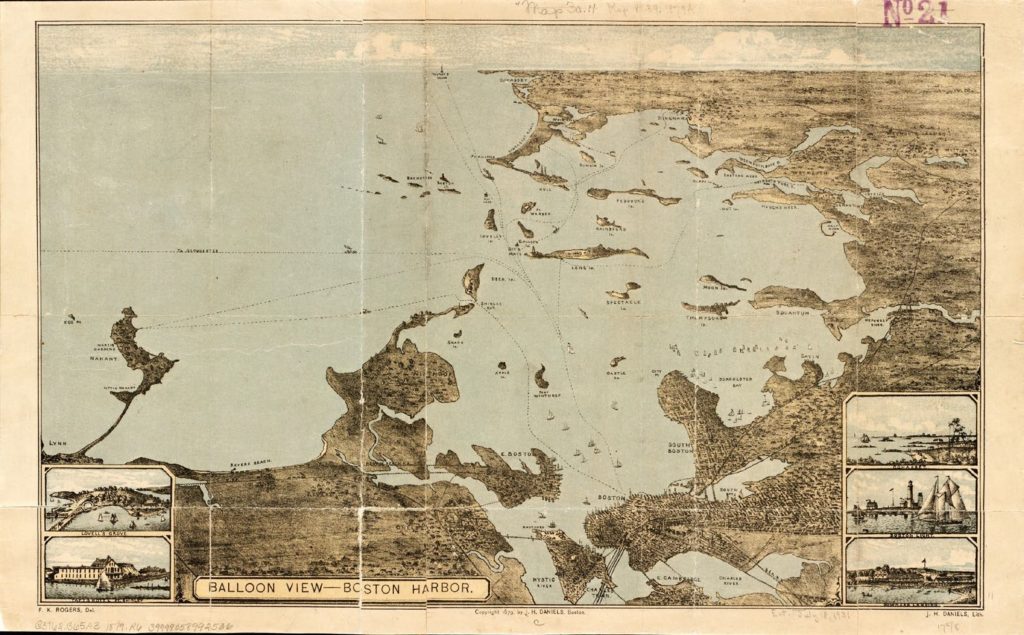

From that high above our apartment, you would be able to see the stretch of Boston Harbor with buried stories of past epidemics: Deer Island, where mostly forgotten vaccine trials took place in 1918. “To remember the pandemic would have required Americans to accept a narrative of vulnerability and weakness that contradicted their fundamental understandings of themselves and their country’s history,” Nancy Bristow writes of the widespread public amnesia surrounding the virus that killed her great-grandparents at that time.1 She argues that such forgetting is inseparable from America’s other amnesias; like the way the same island was also used as a concentration camp for Indigenous captives during the long Indian Wars of New England. The slave trade at that time flowed in multiple directions: Pequot and Wampanoag captives were sold into sugar plantations on Barbados. The ships carrying them were somewhere among the many moving back and forth that docked near Faneuil Hall, where enslaved Africans and their descendants were sold in the era when Massachusetts was the largest slave- holding colony in what became the United States. The violence on which the U.S. was founded became inseparable from the count- less wars that came to shape American medicine. By 1918, the military backdrop became part of how scientists read the virus’s effects during war: “The destruction, according to the noted influenza expert Edwin Kilbourne, resembled nothing so much as the lesions from breathing poison gas.”2

Tear gasses, the chemical descendants of some nerve gas mixes first devised during World War I, were being sprayed on protesters filling the streets in June 2020. We couldn’t tell if it was gas or smoke or fog that made the air over Boston so hazy as we drove toward the hospital, our first time outside in weeks. It had seemed that the harrowing month of fevers had started to recede, then the triage nurse insisted he go in to make sure the lump that appeared under his skin was not a blood clot. My husband had never been to an ER before. He hung up with the doctor’s office and said, “Let me just go put on better chair,” meaning clothes. We kept misconstructing sentences, like being struggling intermediate speakers of our first language. It was the dialect of Covid: words out of place and missing, verbs conjugated in the wrong tense.

As we drove, the president’s voice filled the car, threatening to send in federal troops. I parked near the ER and watched the ambulances’ red silent lights streaming one by one toward the deserted-looking hospital, thinking how emergencies rarely resemble the ways we imagine them. The roads were so emptied that the drivers didn’t bother with their sirens. It was after midnight. The sky full of helicopters, fireworks and police flash grenades. I opened the car windows and listened. An hour later, my husband called from inside the hospital to say they’re keeping him overnight. Not ready to drive away so abruptly, I scrolled on my phone for a minute. The news that flashed up described how, when masks started to be required in grocery stores, one shopper wore a Klan hood inside. He said it was for public health reasons; I stared at the pictures of him pushing a cart down the organic produce aisle.

News stories are filled with doctors noting how Covid fevers can become a “delirium factory” for patients in intensive care units. But in different ways, the virus was becoming a delirium factory for all of us. When I had been admitted into the ER’s glass rooms, the blue and white geometry on my hospital gown had appeared to be moving like a children’s cartoon. The right half of my face had gone numb, but I didn’t think I’d had a stroke. They had brought me to the room after being swabbed in the parking lot, through the plexiglass with holes for the white rubber gloves sticking out. Resembling a clear plastic phone booth, it was adapted from Ebola testing, designed to handle patients who may be biologically contaminated; in that case, me.

Yellow robot dogs were unleashed in that ER a few days later. The animals can carry screens showing caregivers’ faces from room to room. Their maker first designed them to diffuse bombs and recently introduced them for city policing. Some of the models can also kill human targets. I couldn’t understand why doctors were allowing their patients to be approached like IEDs; the screens could have been mounted on a table or less alienating piece of furniture. But tables wouldn’t also be adept at collecting data on body heat and biological sensing to train the robots’ computer systems for war zones and policing ahead. “Part of it may be that we’re in this strange world of Covid, where it’s almost like anything goes,” one doctor said of the unsettling animals.

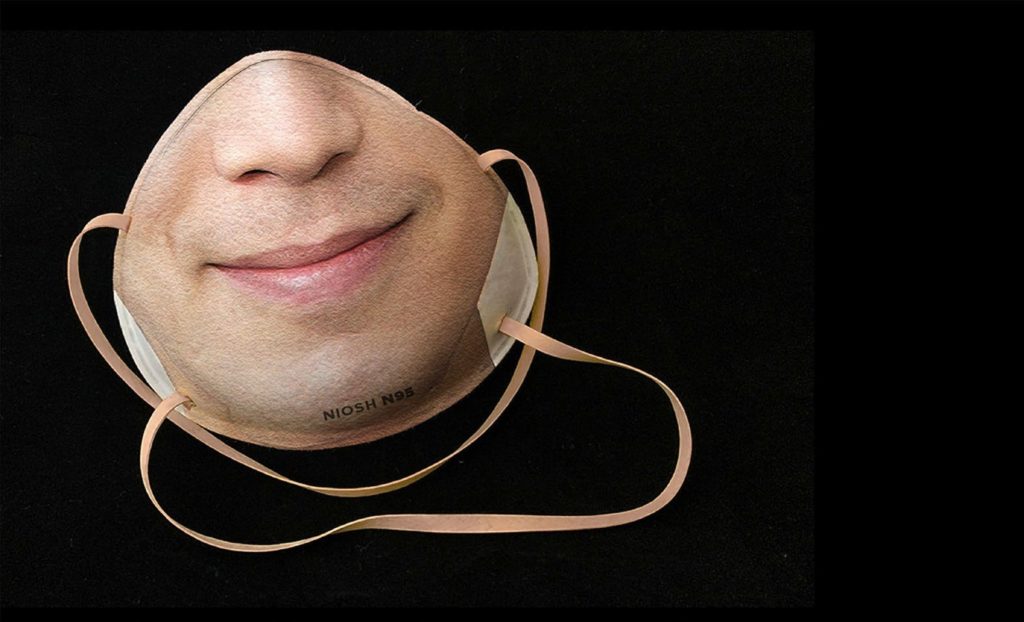

They were part of the pandemic’s circus of capitalism: hazmat suits for clubbing. Custom masks with your real face printed on them, so facial recognition technology still works. Restaurants reopening with stuffed animals seated at the tables, as EPA protections rolled back for living animals. Sports stadiums with sex dolls in the bleachers. Cardboard hospital beds designed to double as coffins. The items for sale materialized unspoken fears and unstable fantasies. After one family made T-shirts reading “Covid Survivors,” their neighbors sprinted away. Others who recovered were pursued “like fairies,” barraged with requests for anti- body-rich blood. By late April, survivor plasma was being sold to corporations for $50,000 a teaspoon. Hard-hit prisons were being turned into hand sanitizer factories. The spectacle of a wealthy country deteriorating into compet ing city-states became a new form of reality TV.

Figure 5. Emptied grocery store shelves in Cambridge, March 2020. Photo by author.

Other things, meanwhile, kept disappearing: things you didn’t think could go away. Some reported washing their fingerprints off, until their iPhones no longer accepted their touch as ID. Or emerged from their fevers with entire stretches of memory missing. When the afflicted first began losing smell and taste from the virus, at first it seemed it would resemble the movie Perfect Sense, a sensorium of loss that occurs in a shared or der. But instead, different things happened to everyone. I was among those who lost vision in one eye, but checklists only included lost smell linked to milder cases. Some reported that coffee smelled like gasoline or that food tasted like paint. Others rinsed their TV remote controls when they tried to do laundry, or couldn’t remember what type of car they drove. We all began to make museums of ourselves, gathering up masks and artifacts imagined at first to be the fleeting ephemera of an outbreak. Familiar shows and movies suddenly felt unwatchable; people inhabiting old routines of human contact in bars and offices and buses became sad to remember. It would take time to read them as the real museums of ephemera: cultural artifacts of handshakes and hugs and unconcerned movement through crowds of strangers.

Figure 6. Customizable Covid mask for 3D facial recognition. Photo by Danielle Baskin, Maskalike.

My husband had a hard time saying out loud what was happening to him. A loved one he told posted a video on Facebook the next day saying the virus was only a conspiracy. We felt the truth slipping from all sides. The virus itself plays into that: slight, serious. You might have no symptoms, just a few, or every one of them. It can be mild and brief or devastation for months on end. You can feel totally fine and be about to die, which doc tors started calling “happy hypoxia.” Or you can feel yourself in serious trouble of a diffuse kind that hospitals have no medicine for. Caregivers dealt with endless misinformation, as people filled ERs with printouts of rumors. At the same time, there were many things the medical authorities also got wrong. When I’d been asked to come into the cancer center in late March for a biopsy, the doctors, receptionists and patients were not wearing masks. The Surgeon General at the time tweeted: “Seriously people—STOP BUYING MASKS! They are NOT effective . . .” When I got a fever 10 days after that visit, I tried to get a Covid test, thinking of the sneezing in the hospital elevators. I had tried to hold my breath; later wished I had also closed my eyes. Six feet was how many imagine an interval of death and how deep we bury our dead, not actually how far the coronavirus can travel through air, which later studies show is at times more like 13 feet and up to 27 feet on the loft of a single sneeze. But I didn’t qualify on the yes-or-no checklists, because my fever was 100.8, missing the cut- off of 101. After the CDC issued malfunctioning diagnostics, the FDA was slow to authorize other tests for market; then it turned out most of the worlds’ cotton swabs were trapped in a no-fly zone. When I finally accessed a test a month later, the doctor flatly told me not to expect it to work. We were fact-checking with broken tools.

My husband getting sick after me was the worst kind of confirmation. He, at least, was offered a test during the two-week window when they were mostly accurate. We found a way to get there, glad to finally have a bureaucratic trace of what was happening to us. But when the call back came days later, it was to say that the doctor had just found the vial of his test forgotten in a bin; the lab had never come for its scheduled pickup. The swab was no longer viable. With no way to get back for a retest, we kept circling back to the mislaid vial later when we started to feel ourselves verging on crazy, a figure for all the lost chances and answers that could have been.

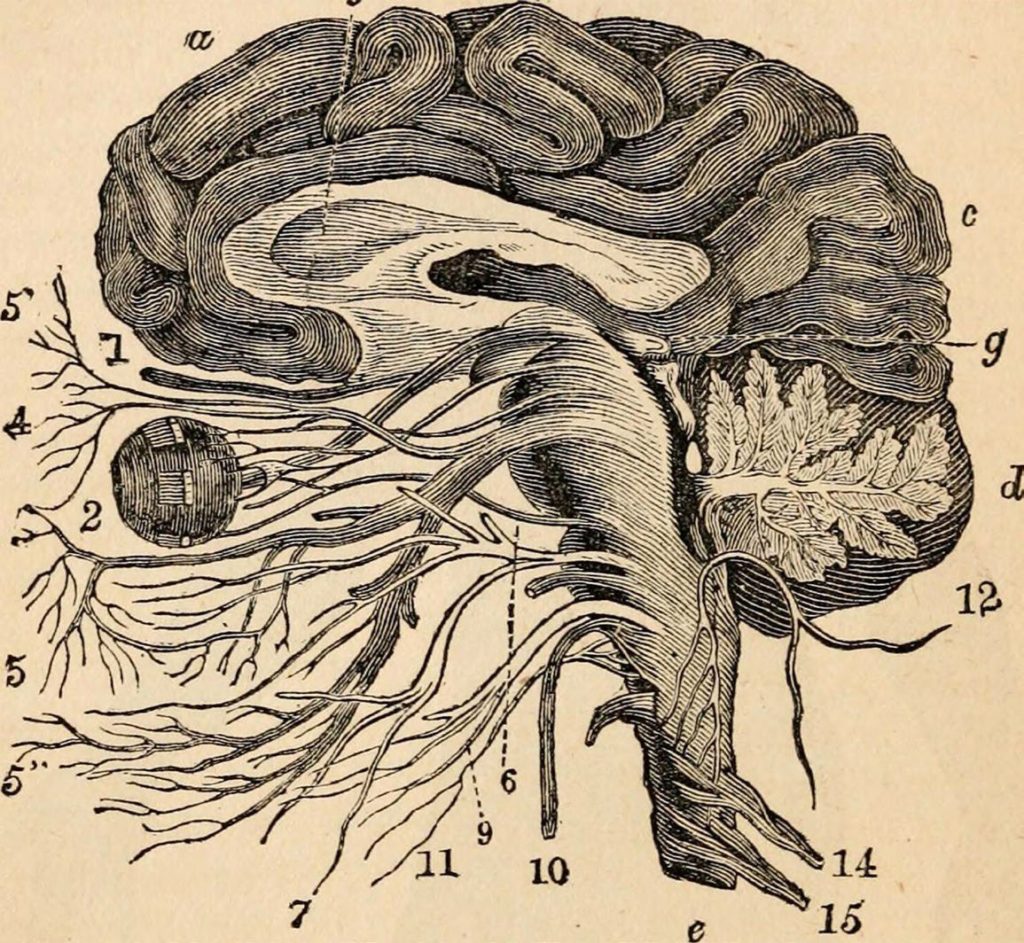

Severe Covid and pneumonia were fully conflated in bureaucracies but not in bodies. It took almost a year for the symptoms being made legible in medical journals to reflect what happened in our home. “Our thinking that [Covid] is more of a respiratory disease is not necessarily true,” doc- tors later observed. “Once it infects the brain it can affect anything because the brain is controlling your lungs, the heart, everything You may never be out of the woods.”3 Their team4 found viral replication 1000-fold higher in the brain. Other studies found cells typically only in bone morrow widespread in the brains5 of those with Covid, part of why the virus’s erratic reach as a circulatory disease6 can cause havoc across the body’s 60,000 miles of veins and fine capillaries. By 2021, other Covid researchers reported “that the very small blood vessels in the brain were leaking . . . a small blood vessel here and a small blood vessel there . . . . The injuries resembled those from a series of tiny strokes occurring in many different areas of the brain.”7

Figure 7. “The Nervous System and General Sensation,” c.1870 textbook. Image in the public domain.

It took Boston months to begin dismantling the hockey rinks it had turned into sprawling clinics no one really needed. Gradually experts began responding to the range of debilities and slow-motion disaster actually happening rather than the more homogeneous cataclysm that modelers initially projected. One doctor referred to the odd regulations and phantom statistics conjured in those early months as “projections of the bureaucratic unconscious.” Ninety-five percent of cases that make up the pandemic never end up in ICUs: families waiting at home or dealing with fallout, moving in and out of legibility, millions of people around the world going through their versions of this.

Alone in a car out front of the ER that night, I decided to check emails before driving away. It seemed like a grounding routine. But instead I found a note from a family member saying their household was taking hydroxychloroquine, as if implying we deserved our illness for not doing the same. I bristled, pulling up a web link about the side effects of hydroxychloroquine and its older predecessor drug, chloroquine, to email back. Yet suddenly I couldn’t tell if this was fact checking, or if I was lost too in some larger absurdity: The mild drug side effects listed on WebMD were hair loss, bleached hair, skin discoloration, increased sensitivity of the skin to the sun, mouth discoloration. I earnestly couldn’t tell whether those were actually chloroquine’s side effects or whether someone hacked the medical website as a joke because the president had just announced he was taking a variety of it against FDA safety recommendations.

Figure 8. National Guard stationed in front of an upscale shoe store in Boston, June 2020. Photo by Blake Nissen, Boston Globe.

For so many, the American dream was already a delirium factory; in the intensification, I felt the spreading malaise of posttruth disease. I closed my family member’s email and pulled up the news on my phone, taking in pictures of the humvees labeled MILITARY POLICE lining Newbury Street that day, soldiers in camo guarding its shopping boutique windows. I rerouted the GPS to avoid the car on fire near the bridge, near the place a ballot box would also be lit on fire closer to the election. The traffic lights had halos in my vision. I couldn’t tell whether it was the fog still hanging in the air or my senses not being fully recovered. Driving felt so fast no matter how slow I drove.

One morning last January, three of us had sat around the breakfast table: Aunt P and I came out in matching purple sweaters, which my mother-in-law gave us both for Christmas. P always carried around a purse full of photographs from her long life, but you could tell they were selected during dementia: not special highlights, random images. P had since moved to a nursing home and was diagnosed with it too. I wonder whether she understands that she is sick, whether we will ever sit at a table again. If Covid’s erasures are anything like what dementia feels like, and what it’s like for her to have both. Whether I might know what that feels like one day; many specialists anticipate a later wave of neurodegenerative sequelae. Whether there are viral damages in the neurons each of us are using to find words about whatever it is we still remember or start to forget.

During the worst of the fevers, to sleep had meant waking up gasping for air and with double vision, having jolt-kicked myself awake, feeling like I had stopped breathing. “Air hunger,” a doctor would call it later. It wasn’t just something wrong breathing in; we couldn’t seem to breathe out right. After the worst night, I felt like my head was on fire but then suddenly felt no pain, as if high; the euphoria felt intoxicating and scary, since it can be a sign of brain cells dying, but I couldn’t type well enough to Google anything. The space behind my right eye hurt with such pressure that it felt as if the epicenter of everything else, numbness in my face radiating outward from there, burning down my arm. Senses delayed; I put a cold cloth on my neck and felt nothing at all, then a few moments later felt the washcloth suddenly being pressed to my skin after it was already gone. All our scars hurt, as if the virus had probed and found every point of weakness. One day I couldn’t swallow even water and became afraid to drink or eat. Later I found that dozens of people with Covid were re- porting the same nightmares we’d had during fevers: dreams of trying to kick to the surface of the ocean, of being stuck underwater and getting the bends.

Pandemic dreams of the healthy were more popular, compiled into a book by a psychology professor.8 Some sweet, others jarring: That the elderly being embalmed after Covid were not dead. That in the moment before a treatment was injected, someone saw the word cyanide on the syringe and realized everyone who had the disease was being euthanized. That Covid’s symptoms first manifested as dark blue stripes covering a patient’s stomach, like the edge of a flag.

The American healthcare system fit into this dreamscape: some patients paid price differentials of 2,700-fold for the same Covid test in the same clinic, depending on their insurance plans. Some test results delayed for weeks waiting at fax machines in need of repair. Many oximeters had been calibrated for accuracy on mostly white test groups, producing insidious inaccuracies for non-white patients but still trusted to guide the algorithmic loops of ventilators. One nursing home was found hiding 17 bodies. P’s nursing home kept giving her heavy sedatives and separating her from any friends she made because she kept talking them into escaping with her again out the window. We weren’t allowed inside. One family suspected their son was accidentally put in a mass grave for the unclaimed. Pollution laws temporarily lifted to accommodate all the ashes. Vaccines and treatments doubled as a fantasy space for people’s hopes and fears of one another.

Health systems around the globe began running out of basic medicines: insulin, ARVs, antibiotics, the closures of hard-won dialysis units and chemotherapy centers. One colleague from Indonesia said that just when it seemed as if things couldn’t get more surreal, all the politicians distributed bottles of hand sanitizer with huge pictures of their faces staring out from the clear gel.

I kept listening to Radio Influenza, as if to find out what could happen next. The show features news items from each date during the 1918 pandemic, read out loud by robots: breakdowns of all kinds being blamed on the virus, mingling in the nervous systems of families and countries.

Months later a neurologist would scroll through my speckled brain images; no answers, but kindness as he told me about mice that regrew brain cells when they exercised on a wheel. He read me the memory tests: “Who is the president?” I recalled when that would have felt like a shared reality check. He continued the test: “Spell WORLD backwards.” I had to picture WORLD in a mirror to answer. He said I have slowed processing speed but that it will probably come back.

Watching the U.S. election results in November, it felt like the country was suspended in those tests: Who is the president? How much might come back? World in a mirror. Covid cases reached new peaks as we waited for election results, two counts growing together. I kept seeing white sparks from time to time that resembled the edges of Fourth of July fireworks.

Maybe it’s a symptom of delirium when everything feels like a metaphor of body and country, or a concretization of the world we have made. Back when they injected contrast and put me into the machine, I’d felt the warm dye circulating through my veins and recalled the first time my doctor sent me to the ER. They explained then that it could be a viral meningitis, or inflammation from my own immune system trying to attack the nerves in my head; but said even if they did a spinal tap and found Covid, there was no medicine they could offer yet to help the body clear a virus there. They discharged me around sunrise, saying to come back if I had seizures or started to feel con- fused. I still kept mixing up words and could remember only the names of my immediate family members with time and difficulty. More confused than that, they clarified. They said to come back if I can’t remember who I am.

I felt stuck in time, leaving again through that exact hospital door where I departed the cancer center the month before. A spinning knife that time had carved out four blueberries worth of my tissue, and I recalled being dazed then too; how after when I crossed the bridge, a train with no passengers rattled by. We were high above the river. I hoped that whatever was dripping from my bandage was mostly the melting packet of ice, and wondered where in the world its water had come from and whether that place too had its water mixed with chemicals and melting ice. What had they given me, was it wearing off or kicking in? They said only to take Tylenol, but the stores were sold out. And I felt the shock of change everywhere and in myself, saw how the parks and streets and grocery stores filled with medical gear on the way home looked transformed into a patch- work of clinics. I walked and walked until it looked like all the beds and units that had been cut from our public health system for decades9 were not eliminated, just displaced; that all the costs of our country’s enduring disparities10 and all the ecological shocks sustained by our planet11 and all the dismantling of the governing bodies meant to protect us had finally left no alternative but to reconfigure our whole world into a hospital.

March blurred into April like biopsies into swabs, long exposures into gradual culminations. But this time I had a fever and the sky outside the hospital was bright white. I tried to look around slowly, not able to turn or bend my neck. I lifted up the papers to eye height and read the instructions again. The Covid discharge papers were full of details about strict isolation but no mention about how people should get home without endangering anyone else. I took slow steps, burning with chills, so tired that the ground appeared to be moving but afraid to fall asleep because then I would be back choking underwater. The thin hospital mask seemed to be dissolving into my face with sweat and snow. When I wrapped the homemade mask cut from an old shirt overtop the paper one, I thought of the people I had seen when I last wore that shirt in a dissembled world months before and reminded myself of their names as I walked, repeating them in my mind and the location of the home I was trying to reach, listing these things that seemed to prove both they and I were real. The morning snow landed on my forehead in huge flakes, like a fantasy of exactly what would make a fever feel better. It was so comforting as I walked that it became harder to trust my senses … Snow in April? Walking alone down an empty road, retracing the route I walked on the day I think I was exposed in March? Was any of this actually happening? With each step forward it seemed more likely that I was still in a hospital bed full of sticky electrodes, having a fever dream about a closed-down world where there was nowhere at all to possibly go.

Notes

- Nancy Bristow, American Pandemic: The Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 11; Dionne Brand. 2020. “On Narrative, Reckoning and the Calculus of Living and Dying.” Toronto Star, July 4; and Siobhan Senier, Joan Tavares Avant, Cheryl Watching Crow Stedtler, Dawn Dove, Carol Dana, et al. 2014. Dawnland Voices: An Anthology of Indigenous Writing from New England. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press).

- John M. Barry, “How the Horrific 1918 Flu Spread Across America,” Smithsonian Magazine, November 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag. com/history/journal-plague-year-180965222/

- Pratima Kumari, et al. “Neuroinvasion and Encephalitis Following Intranasal Inoculation of SARS-Co-V2.” Viruses 13 no. 1 (2021): 132.

- Ana Sandoiu. “COVID-19 and the Brain: What Do We Know So Far?” Medical News Today, January 15, 2021.

- David Nauen, et al. “Assessing Brain Capil- laries in Coronavirus Disease.” JAMA Neurology, February 12, 2021.

- Hassan Siddiqui, et al. “COVID-19: A Vas- cular Disease.” Trends in Cardiovascular Med 31, no. 1 (2021): 1–5.

- John Hamilton. “How COVID-19 Attacks the Brain and May Cause Lasting Damage.” NPR, January 5, 2021.

- Deirdre Barrett. Pandemic Dreams (War- saw: Oneiroi Press, 2020).

- Thurka Sangaramoorthy and Adia Benton. “Imagining Rural Immunity.” Anthropology News, June 19, 2020; and Stephen Mihm. “Why the U.S. Doesn’t Have Enough Hospital Beds.” Bloom- berg, March 13, 2020.

- Alondra Nelson. “Society After Pandemic.” Social Science Research Council, April 23, 2020; and Nayan Shah. Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco’s Chinatown (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

- Sherri Mitchell. “Indigenous Prophecy and Mother Earth,” in All We Can Save, Ayana Eliza- beth Johnson and Katharine Wilkinson (eds) (New York: One World, 2020).

Amy Moran-Thomas is an anthropologist of health, technology and environment at MIT. Her research bridges ethnographic studies of science and technology (medical devices; chemical infrastructures; technology and kinship) with social histories of health and environment (chronic disease; ecological and planetary change). She is the author of “Traveling with Sugar: Chronicles of a Global Epidemic” (2019).