Roberta Pamplona & Jerry Flores

To cite this article: Roberta Pamplona & Jerry Flores (2019) Police Narratives of Feminicide Cases in Brazil, Anthropology Now, 11:3, 21-30, DOI: 10.1080/19428200.2019.1747895

Introduction

Feminicide is a gender-based hate crime in which (mostly) men target women and girls for sexual assault, general mistreatment and murder specifically because of their gender. Feminicide is a large problem within marginalized communities across the globe and is particularly pervasive in Latin America.2 In 2009, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) used the term “feminicide” for the first time in Latin America’s history. In the Cotton Field case, for example, Mexico was condemned for the disappearance and death of young women in Ciudad Juárez.3 After the Mexican state introduced the term “feminicide” as a legal category, other Latin American states such as Guatemala, Chile, El Salvador, Peru, Nicaragua and Argentina did the same.4 In Brazil, Law 13.104/2015 was created on March 8, 2015, introducing the term as a qualifier for homicide in the criminal code. This le- gal shift created a formal process for police to investigate feminicide and gender-based violence for the first time in the history of the country.

Using one year of ethnographic field notes, short interviews with police and an extensive review of police documents, we present this discussion of how various gendered, racialized and class-specific perceptions of women who have been murdered affect feminicide investigations. In other words, we find a disconnection between the goals of the feminicide legal precedent and how the police conducting these investigations implement it. The rest of the article goes as follows: First we discuss relevant research on feminicide in Latin America. Then we briefly discuss intersectionality, which is the framework we use to analyze this issue. We follow this with a discussion of our methodological approach, and then we jump into our findings. We close with a brief discussion of the implications of our research and suggestions for future work.

Background

Historically, the term “femicide” first emerged in Diana E. H. Russell’s testimony in the Inter- national Court of Crimes against Women in Brussels in 1976.5 The 1992 work Femicide: The Politics of Woman Killing by Diana E. H. Russell and Jill Radford also introduced the term to describe the murders of women. The authors conceptualized femicide as a form of gendered violence in which desires of power, domination and control by men are evident. Violence signified by the term “femicide” included a broad continuum of violence that included sexual abuse, domestic violence, sexual harassment and murder and that rep- resented a form of patriarchal control.

In Latin America, the use of a similar category — feminicide — dates from 1980 in the Dominican Republic by feminist activists.6 However, the term has taken on a different meaning based on murder allegations of women in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, pointing to the Mexican state’s general indifference toward the murder of women in this city.7 The multiple demands for such state responses culminated in conventions for the eradication of violence against women, such as 1994’s Convention of Belém do Pará, in which countries in Latin America and the Caribbean began to formulate specific laws on violence against women.8

Even though the terms “femicide” and “feminicide” have been used synonymously, they are conceptually distinct.9 Feminicide emphasizes the state’s complicity in perpetuating violence against women and its impunity.10 This impunity often derives from a social construction among victims who deserve to have their death investigated. In this scenario, the term “femicide” is used by women’s movements to take back state re- sponsibility in any case of a woman’s death or disappearance. Discussions about feminicide have been receiving increased attention. In this sense, the interaction between feminist scholars in Latin American, social movements’ claims and even reports from international organizations defending women’s rights resulted in a series of materials on the theme.11 Even as a formal legal category for police across Latin America, researchers are finding it difficult to understand why feminicide, if considered as a single legal category, can be applied in various ways. Given this uncertainty, it is necessary to look into how the legal category of feminicide. Our article begins to address this issue.

In this article we use an intersectional approach that attempts to address the various unique identities that influence people’s lives. In addition, we investigate how these identities bring about different institutional responses to these women. An intersectional framework provides “an account for the multiple grounds of identity when considering how the social world is constructed.”12 Of importance, intersectionality scholars do not universalize experiences as representative of any one identity category; instead, intersectionality scholars outline a powerful set of interlocking cultural and social forces that shape a group of experiences without con- flating or homogenizing them,13 and without dispensing with the individual dimension. Additionally, intersectional analysis provides an account of how the women’s worlds are constructed in an effort to underscore the constrained nature of individual agency and show the impact of interlocking structural oppressions in devaluing their voices. We apply this intersectional analysis in our research.

Methods

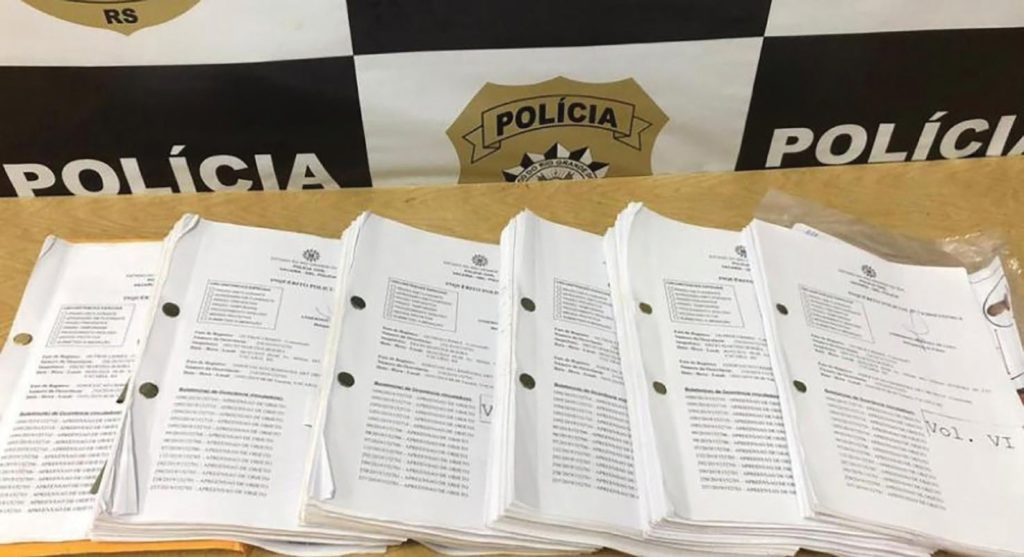

We conducted our fieldwork and data col- lection in Porto Alegre, the capital of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, between March and June 2019.14 We chose this city because its average number of female homicides (4.3 per 100,000) is close to the national average (4.8 per 100,000) and this average has not varied much in recent years. The bulk of our field- work consisted of analyzing 19 feminicide police reports.

We scanned these 19 records in two police stations. To access the reports, we had to talk with officers at the stations. Each visit, we were able to scan two or three reports, depending on how many were available at the time. Going to the police station allowed us to hold meetings with the police officers, who helped us understand the documents we analyzed.

We conducted interviews of 20–30 minutes each. We interviewed a total of 16 officers. In addition, we recorded field notes during every visit. We discuss our findings in detail next.

Findings

During our review of these official documents, we found that officers use a two- pronged organizational system. Although all of the cases we reviewed fell under the category of feminicide, officers divided the cases into two groups. They described the first as feminilidade da casa (“house femininity”). This type of gender category consists of cisgender heteronormative monogamous relationships. Most of the women in this category had long-term partners who were men, were middle aged, were considered middle class and performed all of the duties associated with “traditional” expectations of women (e.g., cooking, cleaning, raising children). Police officers and official reports described the second category as feminilidade da rua (“street femininity”). Officers often placed a woman who veered from gender- conforming behavior into this category. This included women who overtly expressed their sexuality, had multiple partners, had a job in informal economic, drank alcohol, used drugs, lived in a poor neighborhood, or spent an “excessive” amount of time in the street or other public spaces. In the context of Brazil this simply means someone was self employed or worked for someone who was self employed. not under employed. Often officers assumed that women who fell into this category were sex workers or involved in criminal activity. Overall, police offices and criminal justice agents grouping individuals into these categories is not atypical.15 How- ever, we found that officers take a completely different approach to investigating cases for women who fall into each category.

Analysis of Police Investigations

The categorization of women into feminilidade da casa or feminilidade da rua is a multiple-stage process. This begins before officers actually start their formal investigation of any feminicide case. As one officer mentioned during an interview, the police first attempt to understand the life of the woman who was murdered by rebuilding the victim’s past, asking other criminal justice agents, “Who was this woman? Who was she involved with?” A local police chief described this process:

The first element in a feminicide case is asking who was this woman as a human being? We look for an old criminal domestic violence complaint or even if she was threatened by someone in the past. After this, we take a look at the crime scene. We try to see if it is a home or domestic space or a common area. Or is it a place where females are often murdered?

This police chief sheds light on the categorization process that police follow when be- ginning a feminicide investigation. He aptly pointed out how police attempt to build a portrait of the murdered woman before be- ginning any other part of their investigation. While following this process, they also take into consideration the victim’s age, occupation and place where she was found dead.16 Once police officers build this initial profile, they interview people considered close to the victim, such as her family, neighbors and friends. Based on which category the victim is placed in, officers will formulate different questions, evidence and motivations about the violent act.

Feminilidade da Casa

Once officers classified a woman as a feminilidade da casa, they attempted to understand the relationship of the victim and the perpetrator. The police focused their investigation on the experiences at home and within the monogamous relationship. They interviewed friends and family members and asked questions about their relationship, whether the woman experienced abuse and if she had talked to friends and family about being victimized by their partner. The officers specifically asked the victim’s friends and family about her temperament, sexual history and history of abuse via her partner. However, the police placed an emphasis on questions about abuse and victimization. The following quotes emphasize this line of questioning:

Her aunt states that she does not know if the accused beats her regularly, but she does know he is often aggressive toward her. She only knew that husband1 had a strong, more aggressive temperament. (Inquiry 15)

Her neighbor said that the victim always reported the difficulties she was having with her former partner during the seven years of their relationship. She said that that victim has always been assaulted by him. (Inquiry 19)

When officers questioned friends and family about the women who were killed, they tended to ask questions about the mistreatment the victims experienced at the hands of their long-term partners and spouses. For these officers, only women in long-term partnerships fell into the category of feminilidade da casa. They also tended to emphasize feelings of sympathy when discussing these cases or speaking to family members. Through these inquiries and our in-person discussions, officers shared that they had compassion for these murdered women, because they were “good girls” who “followed the rules.” As we show later, this is in stark contrast to women who were classified as feminilidade da rua.

For women who fit into this category, the police reports emphasized problematic moments that existed in the relationships of the women who were murdered. These included times when the women left the men because of abuse and times when these women had reported to friends and family the mistreatment they experienced at the hands of their partners. In these reports, officers highlighted the times when couples separated and the men attempted to reconcile with their spouses prior to the murder:

Witness reported that the accused was talking to the victim in order to resume the relationship, but she refused to reconcile with the accused due to his history of assaults against her and the efforts she had already made. (Inquiry 4)

Her father stated that his daughter told him that Helio17 goes out for drinks and, after he gets home, they usually argue, and the accused can become aggressive [And won’t take him]. (Inquiry 13)

Both excerpts identify instances when women experienced problems with their spouses. In both of these situations, each woman was ready to leave her partner indefinitely. Despite these attempts, these women were eventually killed. However, officers emphasized these attempts to leave when re- porting on these feminicide cases.

Finally, when reporting the deaths of women in the feminilidade da casa category, officers pointed out the moments when the men physically assaulted their spouses or demonstrated overt violence:

In the moment of the crime, the accused appeared to be “possessed” and attempted to beat the victim again and again. (Inquiry 16)

… due to excessive feeling of possession that the accused demonstrated aggressive and explosive behavior at the end of the relationship [and prior to her murder]. (Inquiry 8)

When compiling these reports, the police officers included the physical abuse that the partners inflicted on their partners. When re- porting on these events, officers also emphasized how many women experienced abuse and are eventually killed at home with few ways to defend themselves or call for help. For woman who embodied feminilidade da casa, officers highlighted the partners’ history. Overall, officers felt that these women’s murders were unjust and rightly classified as feminicide. However, police seldom intervened, even when these women reported their victimization to authorities.

Generally, the officers felt that these murders, which they classified as feminilidade da casa, could be solved without difficulty. Officers easily found friends and family who would speak on “behalf” of these women. In other words, officers could find individuals who verified that these women engaged in gender-conforming behavior and attempted to maintain their monogamous relationships. Moreover, most of the women in this category were killed by their long-term romantic partners. This meant that officers could easily identify, arrest, and prosecute these individuals. On the whole, officers attempted to solve these cases quickly and conducted their investigation with care and compassion. In the fol- lowing section, we discuss officers’ approach to investigating and reporting women who they classify as having a “street femininity.”

Feminilidade da Rua

Officers believed that the cases of women whom they classified as feminilidade da rua were difficult to solve. This was largely connected to their belief that it would be difficult to find witnesses who could provide information on these women’s murders. Addition- ally, when starting these investigations, officers often assumed that these women were sex workers, had multiple sexual partners or generally were involved in some type of illegal practices. Finally, unlike their process with the feminilidade da casa, officers often focused these investigations on the streets, where they felt these women spent most of their time, instead of interviewing their friends and family. One police officer said, “She is always in the streets. She should be aware of the consequences.” The police chief of this precinct said this about the same woman he felt was a sex worker:

It will be hard to get a witness and to know the reasons for the murder in this case. She had no proper relationship with [the man who killed her]. I mean, she is a whore, she does not have a proper partner.

Officers felt that the cases of the women in the feminilidade da rua were hard to solve. This was in part because of the officers’ gendered and sexist perceptions of the victims as sex workers and as overtly sexual women who spent “too much time” on the streets and not enough time in the home. Given these perceptions, officers were slow to investigate these cases, as they felt it was unlikely they could arrest the murderer. These excerpts also begin to show the gendered nuances of police officers’ perceptions of feminicide cases and who they feel is worthy of attention and police resources.

When conducting research on women in this category, police officers often asked questions about these women’s previous crimes and gendered nonconforming behavior. Moreover, they avoided asking questions about the relationship between these women and their attackers. In these reports, officers focused on the times that these women participated in drug use and other crimes before they were murdered:

The victim’s sister affirms that Fabiana (the victim) used to go to the church, but since 2016 she has stopped. She does not know if her sister uses drugs or alcohol. (Inquiry 1)

The victim’s neighbor believes the two were drug users and that the accused used to sell drugs on the street. (Inquiry 7)

Both of the excerpts just presented emphasize their previous drug use second. In the second excerpt, officers indicate that the woman who was murdered and her partner were both involved in the drug trade. For women in the feminilidade da rua, this is typical of how officers approach the investigation of their deaths. Instead of focusing on the violence and abuse that these women experienced (as with the feminilidade da casa category), they emphasize the criminal acts in which these women engaged and the crimes of the men who murdered them.

For women in this category, police officers emphasized the victim’s perceived overt sexuality when reporting on her murder. This included discussing the women’s sexual history and a discussion of their having multiple sexual partners:

The accused and the victim went to take a shower and then went to the bedroom, where they had sex without a condom. (Inquiry 2)

Pieces of information suggest that the victim had sex with several men. (Inquiry 19)

In both excerpts, officers emphasize the woman’s sexual practices. In essence, a woman’s sexual practices have little to do with her eventual murder. However, officers feel the need to add this detail into official reports of feminicide. In these cases, police officers did not treat the murders of these women as atypical. Instead they felt that “these” woman were well aware of the consequence of being involved with multiple partners who could be “dangerous” men. Overall, they felt that women categorized as feminilidade da rua were less deserving of the feminicide label and of a speedy police investigation. We can also see how officers’ perceptions of these women’s sexual practices negatively affected their investigations. On the whole, the cases of these women were treated significantly different compared with women classified as feminilidade da casa. The narratives in this section highlight a woman’s possible link with prostitution and trafficking, her precarious or nonexistent employment and the fact that she lived in a poor neighborhood.

Conclusion

Feminist scholars have shed light on more nuanced accounts of how gender and intersecting identities shape the criminalization process. In this article, we use an intersectional analysis to understand the nuances that shape police investigation and reporting procedures of feminicide cases in Brazil. Our interviews, field notes and analysis of institutional documents demonstrate how officers divide women into two distinct categories based on their racialized, gendered and class-specific perceptions of woman who were murdered. We also demonstrate how police perceptions have very real consequences for the woman murdered as well as for her friends and family. We describe how the same legal mechanism for exploring feminicide is shaped strongly by multiple inter- locking identities and results in a two-tiered system for women in this city.

Given our relatively small sample, future research should continue to explore the social meaning of violence by police from an intersectional framework, which provides a tool to understand how this particular institution frames the murder of women. Additionally, we need to further explore how the services that women receive are framed by their multiple and interlocking identities. It is also important for this research to be reproduced in other parts of the world. It would be particularly insightful to understand how these findings would differ if the study were conducted in a part of the global North. A longitudinal study around this issue would help shed light on this understudied topic.

Notes

- We use the term “feminicide” instead of “femicide” to emphasize the idea of state responsibility, referring to an extreme manifestation of violence against women and girls resulting in their death in a context of institutionalized discriminatory gender relations sanctioned by the state. See Fregoso and Bejarano (2010) for an extended discussion on this term.

- P. García-Del Moral, “Feminicidio, Transnational Legal Activism and State Responsibility in Mexico,” PhD thesis. Sociology Department, University of Toronto, 2016.

- P. García-Del Moral, “Transforming Feminicidio: Framing, Institutionalization, and Social Change,” Current Sociology 64, no. 7 (2015): 1017–35.

- MESECVI, “Third Hemispheric Report on the Implementation of the Belém Do Pará Convention,” OEA/Ser.L/II. OEA/Ser.L/II.7.10 MESECVI/I-CE/ doc.10/14 Rev. 1, 2017. http://www.oas.org/es/ mesecvi/docs/TercerInformeHemisferico.pdf.

- W. Pasinato, “‘Femicídios’ e as mortes de mulheres no Brasil,” cadernos pagu 37, July-Dec. (2011): 219–46.

- R. Fregoso and C. Bejarano, Terrorizing Women: Feminicide in the Americas (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010).

- García-Del Moral, “Transforming Feminicidio.”

- Pasinato, “‘Femicídios’ e as mortes.”

- J. Mujica and D. Tuesta, “Femicide penal response in the Americas: Indicators and the mis- uses of crime statistics, evidence from Peru,” Inter- national Journal of Criminology and Sociological Theory 7, no. 1 (2014): 1–21.

- M. Lagarde, “Preface: Feminist Keys for Un- derstanding Feminicide: Theoretical, Political, and Legal Construction,” in Terrorizing Women: Femi- nicide in the Americas, ed. R. Fregoso and C. Beja- rano (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), XI–XXVII.

- It is important to point out the United Na- tions Protocol (UN, 2014) on investigations on the death of women, which proposes precise guide- lines for investigative practices to address gender elements.

- K. W. Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color,” Stanford Law Review 43 (1991), 1241–1299.

- K. W. Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins.”

- The data we present here are part of a multisite ethnography conducted in the city of Porto Alegre between August 2018 and August 2019. In this article we present one portion of our aggregated data.

- J. Flores, Caught Up: Girls, Surveillance, and Wrap-Around Incarceration (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2016).

- In Brazil, having a permanent address or living in an expensive neighborhood is often an indicator of being middle class. In addition, if a woman’s body is found in a poor neighborhood, police often interpret this as a sign that the woman was poor or working class.

- All names mentioned in the article are fictitious.

Roberta Pamplona is a M.A. student in sociology at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. She is an international visiting graduate student in the sociology department at the University of Toronto, funded by the Emerging Leaders in the Americas Program scholarships. Her areas of interest include sociology of crime, punishment and law, and gender studies.

Jerry Flores is an assistant professor in the sociology department at the University of Toronto. He earned a Ph.D. in sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara in 2014. His areas of interest include studies of gender and crime, prison studies, alternative schools, ethnographic research methods, Latina/o sociology, and studies of race and ethnicity.

Appendix

Data collection for the corpus can be viewed in the following places of investigation:

- The Specialized Women’s Assistance Office (SWAO)

- The Homicide Division (HD)

Records

| Record Police Inquiry | Investigation Year | Investigation Place |

| Inquiry 1 | 2017 | SWAO |

| Inquiry 2 | 2018 | SWAO |

| Inquiry 3 | 2018 | SWAO |

| Inquiry 4 | 2018 | SWAO |

| Inquiry 5 | 2016 | HD |

| Inquiry 6 | 2018 | SWAO |

| Inquiry 7 | 2015 | HD |

| Inquiry 8 | 2015 | HD |

| Inquiry 9 | 2016 | HD |

| Inquiry 10 | 2018 | SWAO |

| Inquiry 11 | 2018 | SWAO |

| Inquiry 12 | 2017 | HD |

| Inquiry 13 | 2018 | SWAO |

| Inquiry 14 | 2015 | HD |

| Inquiry 15 | 2017 | SWAO |

| Inquiry 16 | 2019 | SWAO |

| Inquiry 17 | 2016 | HD |

| Inquiry 18 | 2018 | SWAO |

| Inquiry 19 | 2019 | SWAO |