To cite this article: Alexander L. Fattal & Julián Mejía Villa (2020) War Through the Looking Glass: Portraits of Former FARC Guerrillas in the “Truck Camera”, Anthropology Now, 12:2, 70-79, DOI: 10.1080/19428200.2020.1825301

Alexander L. Fattal & Julián Mejía Villa

Explaining how and why I recorded life-his- tory interviews with former guerrillas from the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) in the back of a moving truck—transformed into a giant camera obscura—requires backtracking to 2001. It was then, in a year immediately after graduating from college as a Fulbright Scholar, that I began teaching photography to young people in Colombia. Many of those youth had been displaced by the Colombian armed conflict and had fled from war-torn rural areas with their families to the hilly outskirts of Bogotá. The students captured earnest and compelling images of their everyday lives. As my scholarship year was ending, I worked with a team to transform the project, Shooting Cameras for Peace (Disparando Cámaras para la Paz), into a Colombian nonprofit organization. The nongovernmental organization operated for eight years, teaching photography to about 1,000 students through an evolving curriculum. During that time, the students’ works circulated widely in exhibitions and publications, from the facades of their humble homes to the foyer of the United Nations General Assembly building in New York City.1

In 2011, the Peabody Museum invited me to curate an exhibition of the students’ works. I returned to the community and spoke to former participants, many of whom had had children of their own. As they reflected on their time with Shooting Cameras for Peace, it became clear that of all of the pedagogical exercises we had introduced, transforming recycled cans and boxes into pinhole cameras, miniature camerae obscurae, left the deepest mark. Their fond memories helped me appreciate the power of the camera obscura to capture people’s imaginations. This, in turn, sent me back to the library to research the history of the camera obscura, the optical effect of light streaming through a tiny hole into a darkened space and onto a reflective surface. The image appears on the reflective surface upside down and reversed (left/ right) (see Figure 1). The technique pops up as technology, magic and metaphor in an array of contexts from Aristotle to Marx, but I was most moved by the work of Abelardo Morell, a Boston-based Cuban photographer who is a doyen of camera obscura photography.

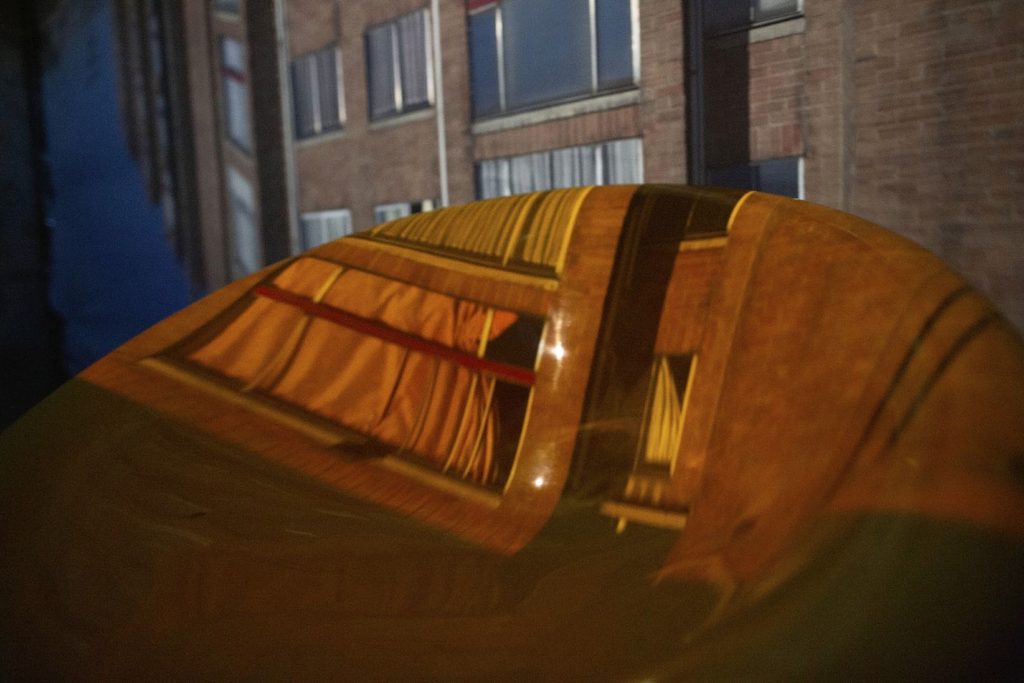

Morell transforms the insides of houses and offices into giant pinhole cameras to create beautifully textured images that play with the superposition of interior and exterior worlds. (He also works with a tent fitted with a periscopic lens jutting out of it to create a similar effect, imposing images of the American West [outside the tent] on the textures of ground surfaces [inside the tent]).2 I experimented with Morell’s technique, but my pictures of friends’ houses were not nearly as beautiful as his. I would spend an entire day making one photograph, often frustrated by the constraint of a window’s location. I began to fantasize about creating a mobile camera obscura. Those imaginings led me to transform the pay- load of a small cargo truck into a “truck cam-era” (camión cámara). I bored a five-centimeter hole in one of the truck’s sides and taped a basic lens, crafted by an eyeglass shop, over the new orifice. Inside the truck I hung a white cloth opposite the lens. Sure enough, the image appeared, upside down and reversed.

My camera obscura experiments proceeded in parallel to my doctoral research, which focused on the convergence of consumer marketing and counterinsurgency in Colombia. I was specifically interested in how the government outsourced its propaganda operations that sought to motivate guerrillas from the FARC and National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional) to desert from the insurgency with sleek campaigns. Ethnographically I focused on the military’s “demobilization” program and the advertising firm that the Ministry of Defense contracted, the same one that was stewarding brands such as Mazda and Red Bull in Colombia. I also worked with com-munities of former guerrilla fighters who were transitioning to civilian life.3

Halfway through a two-year-long research stretch, I began to speak with a few former combatants about a visual arts project. At first the idea was to take a series of portraits of them with the truck camera, parking the truck in front of a location that featured prominently in the telling of their life histories. But that was when the truck camera was just an idea, be- fore I had begun the trial-and-error transformation of the truck into a truck camera. The last stage in the metamorphosis involved taping black garbage bags over rays of light poking through the truck’s corrugated aluminum walls to prevent any errant rays from diluting the stream of light coming through the lens.4 Then, with the upside-down image of the outside world projecting onto the white cloth, the driver pressed on the gas pedal. The world transformed as we moved through the city. Bicyclists pedaled in the sky, buildings jutted toward the ground, clouds slid across the floor, and dappled shadows of trees melted sideways as the truck turned a corner.

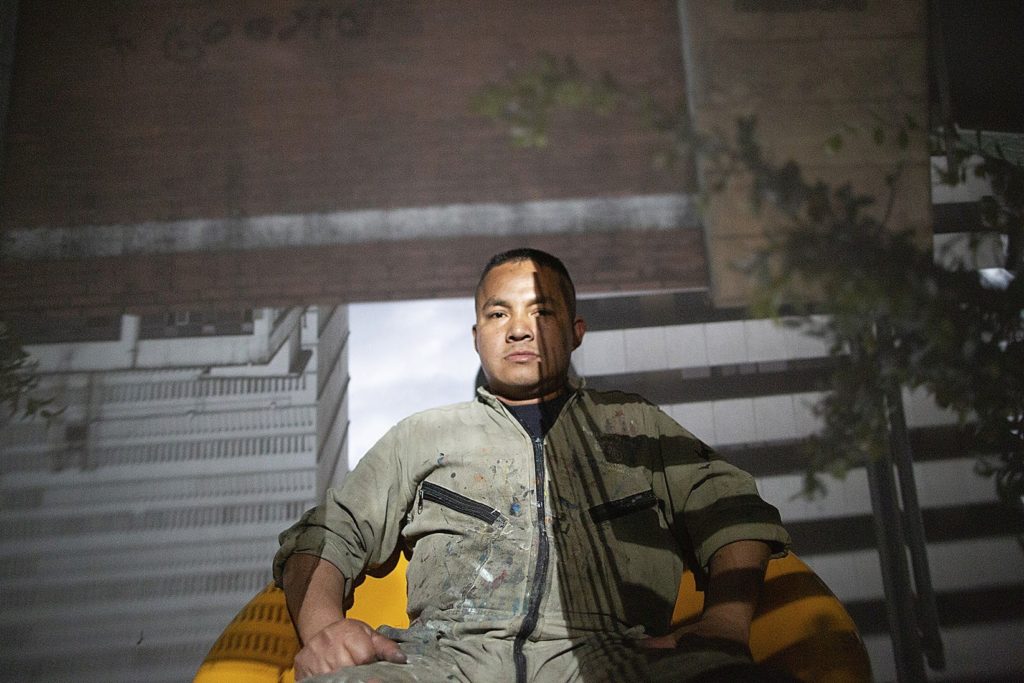

The beauty of these images stirred something inside of me, and I became overtaken with the idea that such an emotional response could be harnessed to foster greater understanding of a population that has generally been deemed unworthy of empathy. Emboldened by my earlier experience making a film in Harvard’s Sensory Ethnography Lab, I grew determined to produce a documentary to foster such empathy and present former guerrillas in all of their contradictions. I wanted to challenge politicized discourses that often rendered them as less than human and therefore disposable—even after they had renounced the armed struggle and reintegrated into civilian life. I was working toward not only my doctorate in sociocultural anthropology but also a qualification in Critical Media Practice. I recorded individual interviews with eight former guerrillas in the truck camera. This photo essay comes from those trips. Most of the photos were taken in quiet moments between recording sessions. I received consent from the participants on two occasions, first as a graduate student researcher and again while producing the material in anticipation of a more public exhibition. Most of these individuals had already been public about their status as former guerrillas and expressed relief about their security after the FARC retracted its policy of hunting down deserters toward the end of the peace negotiating period (2012–2016). In its effort to try to jump-start a political movement, the FARC decided that deserters would be not only spared retribution but also welcome to join the broader movement (even if they were to be excluded from the inner circle of the newly non-clandestine Colombian Communist Party, a determination made on the basis of the gravity of their collaboration with the military5). Short quotes from the interviews accompany the images presented here. The text and images combine to offer glimpses into worlds turned upside down by a radical transition from an underground militant life to that of an ordinary civilian, and from treks through remote jungles and mountains to hustling along sidewalks and survival in the city.

“I am going to summarize, briefly. I was trained with the pistol. You don’t take the pistol course for anything good. That’s all.” — Javier Alexander.

“My dream was to be a big commander …. But I didn’t have that opportunity. I had the chance to do some courses, a nursing course … basic courses. In the end, I lost my morale. I didn’t see any future, not for me or my family.” — Daniel

“If I hadn’t acquired that discipline (in the guerrilla), I wouldn’t have been able to survive in a city like this … I am totally convinced, totally, that real change today won’t come by violence.”

— Sandra.

“The sargeant asked me: “Do you know them?” … I said, “No, I don’t know them.” Deep inside I thought, I can’t say that they’re in the guerrilla, I can’t. They’re the people I lived with.”

— Sandra.

“Son of a bitch, that was from when bullets were flying around … shrapnel got into me …. What’s most dangerous comes from above, the helicopter, when it comes down and isn’t moving, son of a bitch. Don’t even move to get down because you’ll get taken out. And if it’s at night, they throw those lights that illuminates everything and that’s where they drop those grenade-bombs that kill everyone, everyone. You’re lucky to get out of combat alive.” — Evinece

“About a month ago I became unemployed and I don’t have work right now, but I’ve been a warrior, a fighter and I’ve made some resumes to go out and get a job, to look for work and see who can give me work to survive.” — Oscar

“Look, at first everything that happened was beautiful when I took the remedy (yagé)—a small cup but well prayed for, I’d say, by the taita (shaman). I started to vomit lots of things. Brother, when I looked, I had vomited, let’s say in general terms, I vomited an entire hardware store …. I vomited rifles, vomited knives, vomited pistols, vomited hammers, vomited saws, vomited everything.” — Julio Cesar.

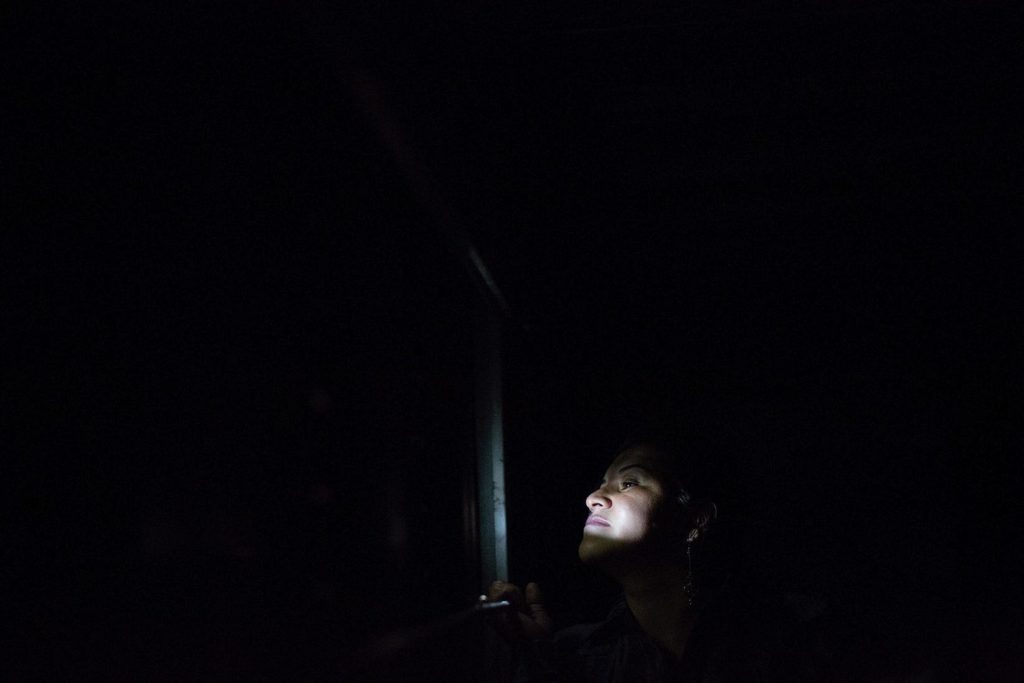

Julián Mejía Villa, director of photography for the documentary Limbo, camouflaged inside the truck camera. The truck looked like any other truck in the city. It turned into a machine that allowed the protagonists to show and hide themselves at the same time, sharing their story but not revealing the neighborhoods where they lived.

The driver of the truck was a kind of coauthor of the images. He was connected with the photographers in the back via walkie-talkie.

The truck camera serves as more than a neutral apparatus for recording participants’ stories; it figures in their narratives by creating a confessional, quasi-psychoanalytic space for them to reflect on lives that are in perpetual motion.6 The truck camera creates a place of encounter where documentarian, subject and, by proxy, spectator are locked together in a dreamlike journey. The truck camera becomes a character in the production of the images—pictures made by cameras inside of a camera. Such a Russian doll approach to photography suggests a paradigm in which images layer upon images in a recursion that goes all the way down to photography’s prehistory. The images that emerge from this montage of cameras in cameras might at first seem too contrived to be illuminating. But it is precisely because they are distorted, flipped and tipped that they can explore the space be- tween the antipodes. This is why I found the truck camera a powerful vehicle to explore the experience of guerrilla warfare, with its gray area of complicities that emerge from the foundational confusion between militants and civilians. In all of the project’s different forms—documentary short, multimodal academic article, photo-essay, art installation— it explores the darkened chamber of former guerrillas’ consciousness in ways that illuminate the nuances and contradictions of people who have been both victims and perpetrators; all these formats call to their public to resist the political reflex to celebrate or condemn and, hopefully, through the magic of pinhole videography, lure people to look and listen.

- Nota de autoría: Estas imágenes fueron tomadas por Julián Mejía Villa y Alexander L. Fattal. Como se intercambiábamos cámaras, a veces no se sabe quien tomó cual imagen.

- Note on authorship: These images were taken by Julián Mejía Villa and Alexander L. Fattal. Since we exchanged cameras, sometimes we don’t know who took which image.

Notes

- For a compilation of the students’ works and my own reflections on the process, see Shooting Cameras for Peace: Youth, Photography, and the Colombian Armed Conflict / Disparando Cámaras para la Paz: Juventud, Fotografía y el Conflicto Armado Colombiano (Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum Press/Harvard University Press, 2020).

- Some of Abelardo Morell’s work can be viewed on his website: http://www.abelardomorell. net/project/camera-obscura/. He also has two books of this work: Abelard Morell: The Universe Next Door (Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago, 2013) and Camera Obscura (New York: Bulfinch, 2004).

- This work was published in 2018 as the book Guerrilla Marketing: Counterinsurgency and Capitalism in Colombia (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press).

- Here I extend my deepest gratitude to my friend Julián Mejía Villa, a talented photographer and historian of art who also dedicated himself to this project.

- The question of what constitutes collaboration is, as the reader might suspect, tricky to say the least. The former guerrillas whom I interviewed prior to the peace accord stated it was important that the FARC retracted “plan pistola,” a policy of assassinating defectors, essentially removed the sword of Damocles from over their heads. Although former guerrillas face many dangers, those who deserted before the peace accord of 2016 feared their former comrades the most, as guerrilla statutes declared deserters legitimate military targets. Since the 2016 peace accord, there have been a spate of killings of former guerrillas, but those have been primarily guerrillas who mobilized after the accord. The circumstances of these deaths are not clear, but most took place in rural areas where there is an active narco-paramilitary presence or in areas where dissident guerrilla factions, who have broken away from the peace accord, have remobilized and are financing operations by taxing the illicit economies of drugs, extortion and illegal mining.

- For an extended filmic representation of such limbo, see my 25-minute film Limbo (Bogotá: Cinema Guild, 2019), http://store.cin- emaguild.com/nontheatrical/product/2622.html.

Alexander L. Fattal es profesor asistente en el Departamento de Comunicación de la Universidad de California, San Diego. Es doctor de antropología de la Universidad de Harvard y artista documental enfocado en el conflicto colombiano y los medios de comunicación. Es autor del libro Guerrilla Marketing: Counterinsurgency and Capitalism in Colombia (University of Chicago Press, 2018) y Shooting Cameras for Peace: Youth, Photography, and the Colombian Armed Conflict/Disparando Cámaras para la Paz: Juventud, Fotografía y el Conflicto Armado Colombiano (Harvard University Press, 2020) y el director de Limbo (2019) y Trees Tropiques (2009).

Julián Mejía Villa es magíster en Historia y Teoría del Arte, la Arquitectura y la Ciudad de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Su trabajo de grado se cuestionó acerca de la construcción de fotografías emblemáticas de prensa en el marco de la masacre de Bojayá (Colombia). Es fotógrafo profesional y ha estado involucrado en diferentes proyectos relacionados con el conflicto colombiano.

Alexander L. Fattal is assistant professor in the Department of Communication in the University of California, San Diego. He received his doctorate in anthropology from Harvard University and is a documentary artist who specializes on the mediation of the Colombian armed conflict. He is the author of Guerrilla Marketing: Counterinsurgency and Capitalism in Colombia (University of Chicago Press, 2018) and Shooting Cameras for Peace: Youth, Photography, and the Colombian Armed Conflict/Disparando Cámaras para la Paz: Juventud, Fotografía y el Conflicto Armado Colombiano (Harvard University Press, 2020) and is the director of Limbo (2019) and Trees Tropiques (2009).

Julián Mejía Villa has his master’s degree in History and Theory of Art, Architecture, and the City from the Universidad Nacional de Colombia. His thesis analyzes the emblematic press images of the massacre of Bojayá (northwest Colombia). He is a professional photographer who has been involved in different projects related to the armed conflict.