Kelly O’Neil

To cite this article: Kelly O’Neil (2019) Making Academic Research Accessible: An Infographic Describing Older Women’s Experiences of Housing Insecurity, Anthropology Now, 11:3, 45-62, DOI: 10.1080/19428200.2019.1747876

Years ago, when I lived in Ottawa, the National Gallery of Canada purchased a painting that ignited a storm of controversy. People were really angry: ferocious defenders and critics verbally duked it out for weeks over the artistic merit, cost and American origin of the picture. I was working in the booming high-tech industry at the time, which meant I was part of the sleepy migration of citizens travelling on public transit to and from the outskirts of the city every day. As the controversy raged about the painting’s purchase, something changed on the bus. People seemed more awake. They were talking to one another — sometimes arguing, and even ranting — about the picture. When people on the bus are talking about some- thing, you know it’s gotten under the skin; you recognize that it’s worked its way into the bloodstream of the community.

In transitioning from community work to academia, I was struck by how rarely academic research makes that same kind of bold journey into the public sphere. A growing perception of the wide gap between university and community knowledge was a motivator to make my master’s thesis research on older women’s housing insecurity accessible to a nonacademic readership. Returning to graduate school as a woman nearing 60, my research attention was drawn to aging women and their marginalization within re- search and society as a whole. This sidelining is significant. Women represent the fastest growing segment of the older adult population,1 and this trend is expected to continue. Within the next 15 years, women 65 and older are projected to make up one-fourth of the total female population.2 Demographically, at least, as some feminists assert, old age is in actuality the domain of women.3

My community work with people living in poverty and in dangerous housing such as homeless shelters and prisons had made clear to me how having a low income invariably translates into being poorly housed. My academic research revealed gaps in existing knowledge about the particular circumstances of aging women within the larger group of insecurely housed Canadians. My own experience growing up in public housing within a low-income single-parent family had taught me early on about the political dimensions of housing. Within the dreary, treeless sprawl of beige row houses constituting an urban housing project I came to recognize, as a child, how housing may be stigmatized and can generate different expectations and opportunities for people living in neighbor- hoods like mine. I’ve come to see a kind of broader, generational narrative about housing insecurity within my own family, where ancestors represent great housing disruptions in history in their flight from the Irish potato famine and the expulsion of Acadians at the hands of the British in the Grand Dérangement of 18th century Nova Scotia.

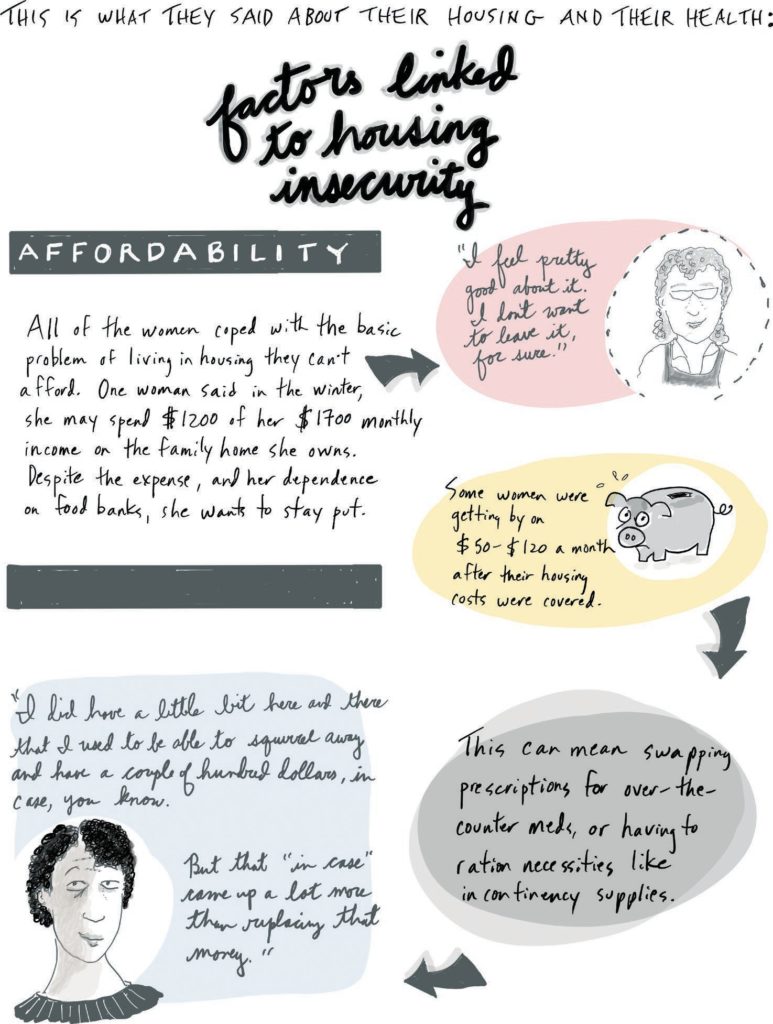

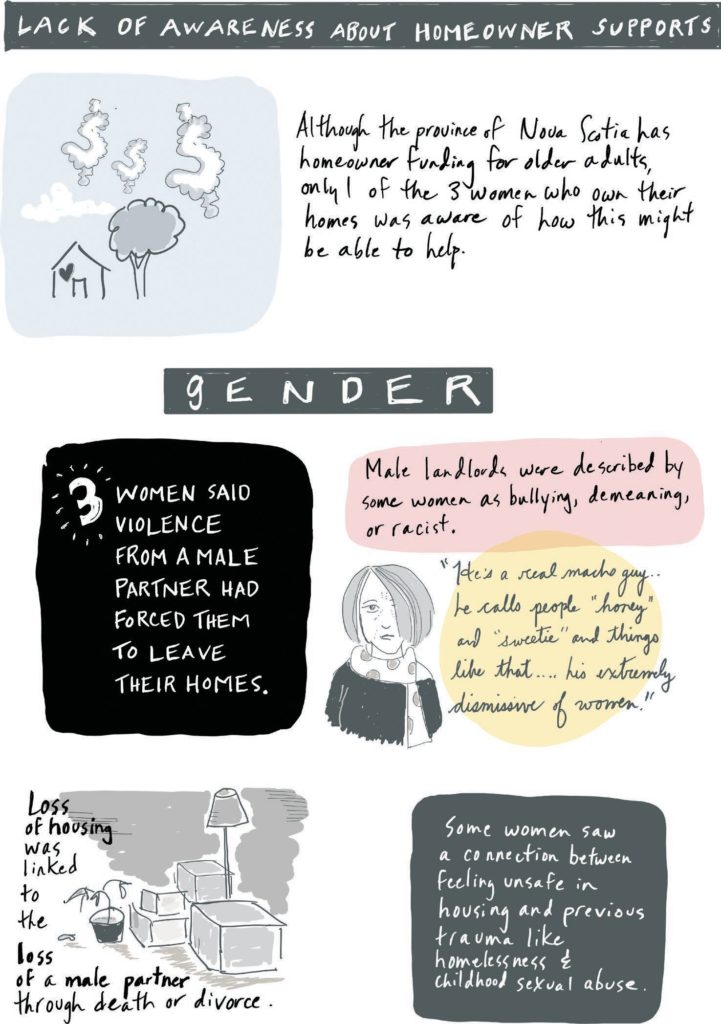

Bringing all of these perspectives together helped direct my master’s thesis research, which was a qualitative study of housing in- security among older low-income women living in Halifax Regional Municipality, the capital of Nova Scotia. In late 2018 and early 2019, I interviewed 11 women aged 54 to 74 from urban and suburban communities within the region. I wanted to find out about their experiences of being insecurely housed and how they might connect their housing circumstances to their health and well-being. As an older woman, I had some insight into how decades of working around sexist and ageist structures can come home to roost for women in old age: in insufficient incomes, inadequate housing and the social invisibility inevitably imposed on aging women as they cease to be objects of interest.

A number of the women I interviewed for this study described a sense of being unseen and unvalued. As one woman put it, “Your expiry date has come and gone.” All of the women struggled with having not enough money on which to live after housing costs were covered; all got by, somehow — one woman lived on $50 a month. Many of the women regularly accessed food banks, and some swapped prescription drugs for over- the-counter meds or strategically rationed necessities like incontinency supplies.

My personal and professional background has shaped a fundamental belief that knowledge that comes from the community belongs in the community. This belief informed an early intention to produce an accessible summary of the core research findings very quickly after the thesis was completed. An avid doodler, I overcame lifelong personal disappointment about my lamentably limited artistic skills and decided to produce, regardless, a visual resource summarizing the study’s core findings. My wish was to present the findings in an engaging, respectful way that was both sensitive to the gravity of women’s circumstances and appropriate for nonacademic readers who, rightly so, were unlikely to ever read a 200 page thesis.

The outcome — variously conceptualized as an infographic/zine/infodoodle/comic- with-decidedly-unfunny-content is presented in the following pages. To encourage dialogue about older women’s housing circumstances, I distributed this resource through emailed links to more than 100 individuals and agencies in the community, including every elected representative for the Halifax area at the municipal, provincial and national levels (several of whom subsequently invited me to share my research findings in person). The visual resource generated media attention, and the research was featured on local radio, television and online news. A lovely elaboration on the document’s accessible focus was generated by the digital artists at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, who creatively distilled the infographic’s text and images in an appealing short animation.4 The entire experience has allowed me to see the vital connection between academics and the community and the role that research can play in linking both to help promote positive social change.

Not long after printing copies of the infographic, I walked into my home to find my brother and niece slouched comfortably on the couch engrossed in reading about the research. I thought, This is what academic research should be doing: getting under your skin; taking up residence in your living room; making you think, and talk, and, perhaps, if we’re lucky, act to change the way things are.

Notes

- Cecelia Benoit and Leah Shumka, Gen- dering the Health Determinants Framework: Why Girls’ and Women’s Health Matters (Van- couver: Women’s Health Research Network, 2009). http://bccewh.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/ 2012/05/2009_GenderingtheHealthDetermi nantsFrameworkWhyGirlsandWomensHealth- Matters.pdf.

- Statistics Canada. Women in Canada: A Gender-Based Statistical Report (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2016). https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/ pub/89-503-x/89-503-x2015001-eng.htm.

- Gemma M. Carney, “Toward a Gender Poli- tics of Aging,” Journal of Women & Aging 30, no. 3 (2018), 242–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952 841.2017.1301163

- https://youtu.be/vfmZlNjEBro

Kelly O’Neil is a Ph.D. student in the Inter-University Doctoral Program in Educational Studies at St. Francis Xavier University in Antigonish, Nova Scotia. Following her firm belief in the dictum, “If you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu,” her research intention is to support political and social empowerment of older, economically marginalized women through collaborative development of a community radio/podcast program. Her master’s thesis, Dimensions of Housing Insecurity for Older Women Living with a Low Income, received the graduate thesis award for 2019 from Mount Saint Vincent University in Halifax.