Books and Arts: Reviews of Books, Articles, the Arts, and More!

Shaylih Muehlmann. 2014. When I Wear My Alligator Boots: Narco-Culture in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands. Oakland: University of California Press.

Shaylih Muehlmann. 2014. When I Wear My Alligator Boots: Narco-Culture in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands. Oakland: University of California Press.

Anna Ochoa O’Leary, Colin M. Deeds and Scott Whiteford, eds. 2013. Uncharted Terrains: New Directions in Border Research Methodology, Ethics, and Practice. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

In one of the many bitter ironies of security and free trade, the United States–Mexico border is popularly recognized as a region of violence, crime, danger and disorder rather than one of connections and free movement as promised 20 years ago with the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). In highly stratified border crossings, barricades for the working poor and “ordinary” travelers contrast with “passage-ways” for business traffic and the wealthy (1). NAFTA coincided with a dramatic increase in the number of Border Patrol agents along the Southwest Border Sector. The 18,611 agents in this sector in 2013 were fivefold the number for 1993. According to a report by the state’s Department of Transportation, the vast majority of NAFTA truck freight between the US and Mexico passes through Texas highways, but migrants and border residents are subject to surveillance and detention at border and interior checkpoints.

Along the US-Mexico border, more than 5,000 migrants died attempting to reach the United States between 1994 and 2009 (2). Migrants, Latinos and the poor are all targets of contemporary security policies, rather than being protected by them (3). For undocumented migrants attempting to cross South Texas, US Route 281 might as well be called NAFTA’s Highway of Death. Extending 1,872 miles from Mexico’s border to the International Peace Garden at the Canadian border, Route 281 runs through the US Border Patrol’s Falfurrias Checkpoint in Brooks County, Texas. Every northbound vehicle passes through this checkpoint, located 72 miles from the border town of Reynosa, Mexico. More than 200 migrant border crossers died in Brooks County from 2012 to 2013 as they walked through the harsh South Texas brush, attempting to circumvent the checkpoint to avoid detention and deportation. As immigration agents patrol isolated ranch lands, migrants scatter attempting to escape, and many are separated from their groups. Coming mainly from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras or El Salvador and injured, disorientated or too ill to continue the journey, migrants die from dehydration in the intense heat.

In 2012, the US Border Patrol recorded 271 deaths in Texas, constituting 59 percent of all border deaths recorded that year and the highest number recorded for the state since the Border Patrol began tracking such fatalities in 1998. These deaths are taking place as the number of migrants crossing the US-Mexico border declines, meaning that the southern border is becoming much more deadly.

The actual number of deaths is much higher than reported since only a fraction of the bodies are recovered in sparsely populated border regions. In Brooks County, for example, thousands of acres of privately owned ranchland surround the Falfurrias Checkpoint, with the King Ranch—one of the largest in the world—running along the east side of the highway and other ranches along the west side. Bodies decompose rapidly in the hot, humid climate and animal predators move or destroy human remains, leaving only scattered bones. In counties along the Rio Grande, migrants whose bodies are recovered in Mexico—including the dozens who drown every year in the river separating the two countries—are excluded from the Border Patrol counts. The incomplete census of migrant deaths contributes to an all too limited accounting of the human cost of border security policies and to a lack of state accountability for such devastation (4).

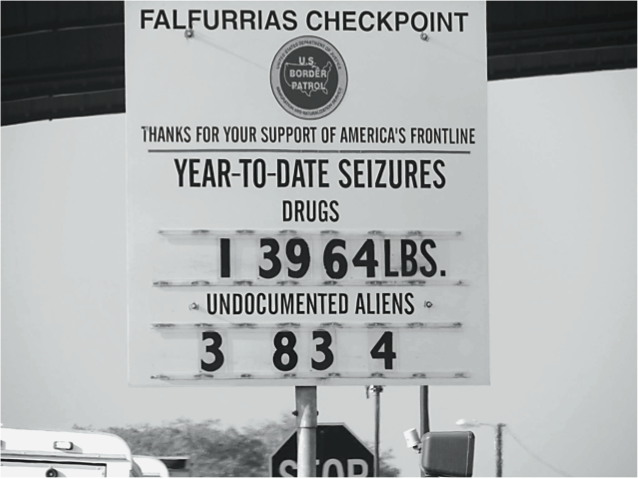

The Falfurrias Checkpoint has one of the highest rates of apprehensions in the country. A large white sign at the checkpoint’s southern entrance announces “YEAR-TO-DATE SEIZURES” in capital letters followed by a tally of drugs confiscated. Below is a tally of “undocumented aliens” apprehended. On February 1, 2014 the sign reported the seizure of 13,964 pounds of drugs and 3,834 “undocumented aliens.” The purpose of the checkpoint as stated by US Customs and Border Patrol “is to maintain traffic check operations to detect and apprehend terrorists and/or their weapons of mass effect as well as to prevent the passage of illegal aliens and/or contraband from the border area to major cities in the interior of the United States via US Highway 281″ (5). By this logic, “drugs” and “illegal aliens” fall into the same category as terrorists, weapons and contraband—all labeled dangerous and illicit and targeted for detection and apprehension.

Popular images of the borderlands as inherently dangerous and lawless obfuscate the ways laws have created violence. US security policies, neoliberal economic reforms and restrictive immigration laws all create the conditions under which migrants risk their lives in attempts to cross the border. Likewise, the violence stemming from Mexico’s war on drugs is closely connected to US prohibition policies as well as security and economic policies. In Mexico, more than 70,000 have died in the militarized drug war launched by President Felipe Calderon in 2006—the poor being at particular risk of death or prison.

Intensified border enforcement and anti-immigrant laws on the US side of the border began well before September 11, 2001. Indeed, the Border Enforcement policies emanating from the Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) “Prevention- through-deterrence” strategy coincided with NAFTA’s passage. The INS established Operation Hold the Line (El Paso, Texas, 1993), Operation Gatekeeper (San Diego, California, 1994) and Operation Safeguard (Arizona, 1994, 1999) in urban regions to concentrate border enforcement in populated areas. These initiatives pushed people to cross in more isolated and dangerous areas, creating what the Binational Migration Institute at the University of Arizona labels a “funnel effect” in which migrants were pushed away from busy crossing points into dangerous regions such as the Arizona desert. As a result, the number of deaths increased twentyfold from 1990 to 2005 (6). As anthropologist Ruth Gomberg-Muñoz notes, these operations succeeded in creating “a public perception of the ‘illegal Mexican immigrant’” but failed to deter migration (7).

Two recent books on the US–Mexico border—Uncharted Terrains: New Directions in Border Research Methodology, Ethics, and Practice, edited by Anna Ochoa O’Leary, Colin M. Deeds and Scott Whiteford and When I Wear My Alligator Boots: Narco-Culture in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands by Shaylih Muehlmann—address how anthropologists and other social scientists can conduct ethical research on border violence, its causes and consequences. They challenge facile and sensationalized conceptualizations of the border and reveal possibilities for conducting ethical research in a highly politicized setting. The geographic scope of Uncharted Terrains includes both the US and Mexican sides of the border, from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico. The volume’s contributors explore multiple aspects of the ethics of border research, from navigating unequal power relations between researchers and vulnerable populations to the connections between scholarship and public policy and the possibilities for creative methodologies such as collaborative research, all within the broader context of concerns about human rights and social justice. When I Wear My Alligator Boots, an ethnography about the impact of the war on drugs in an impoverished rural desert community in Baja California Norte, sheds light on the many hidden costs and consequences of the drug war. It also provides a model of politically engaged anthropological research.

Contributors to Uncharted Terrains include anthropologists, sociologists, geographers and political scientists with years of research experience along the border. All of the chapters are developed from presentations at the Border Research Ethics and Methods Conference held at the University of Arizona in 2010. Research topics include health, drug trafficking, news media and cross-border organizing. An introduction and a conclusion by the book’s editors address the political and economic context of the border, including globalization, increased enforcement and the anti-immigrant discourse used to justify security policies. Chapter authors analyze the complexities and methodological challenges of working with vulnerable populations. Because unauthorized migrants face the risk of detection, deportation, detention and even death along the border, scholars must address these risks in designing and implementing their research. In one chapter, following Jorge Bustamante’s conceptualization of migrant vulnerability as a “social condition of powerlessness” based on migration, contributors Daniel E. Martínez, Jeremy Slack and Prescott Vandervoet note that they are “humanitarians first, and researchers second” (8). In several research projects, they collaborated with a migrant shelter in Altar, Mexico, to support the safety of migrants and contributed in small ways to the shelter itself. Contributors Jessie K. Finch and Celestino Fernández raise the possibility that methodologies can go beyond doing no harm. Drawing from critical race theory, feminist approaches and liberation theology, they note that research may empower immigrant participants by, for instance, incorporating them into research projects, cross-border collaborations and social analyses that reveal policies behind human suffering.

Several chapters address the impact of policies on border populations as well as the potential for border research to influence policy. For example, Jon Amastae, Michele Shedlin, Kari White, Kristine Hopkins, Daniel A. Grossman and Joseph E. Potter show how the redistributions of state funding had significant impact on low-income women on both sides of the border. When money for Planned Parenthood in El Paso, Texas, and financial support for a university hospital in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, were removed from state budgets, the organizations were forced to cut services. In another chapter, Judith Gans challenges many common “frames” of immigration policy research. She exposes how arguments that undocumented migrants drive down wages or create financial burdens are not only oversimplified and incomplete but also fail to take into account moral and ethical issues facing migrants and their countries of origin.

In formulating research topics, conducting fieldwork and publishing results, ethics and methodology are closely connected, particularly, as Rocío Magaña points out, “in contexts as socially, politically and legally complex and volatile as these borderlands.” Magaña’s chapter on the Arizona–Sonora border region emphasizes the need for complete transparency in research, given the multiple and often conflicting interlocutors whom scholars engage at border zones.

Magaña reflects on how and when migrants become or are made visible in scholarship, film and other forms of media and the risk of objectification and commodification of migrant suffering. As migrants are ignored or made visible only as problems—criminals, passive victims, a drain on resources—Magaña notes that ethnographers should be aware of how their knowledge may be appropriated. Her chapter, along with others in the volume, points to the importance of humanizing migrants and border residents, in part through illustrating their connections to families, communities and policies.

The impact of funding sources on research priorities and outcomes, particularly financing from the federal government, is addressed briefly in several chapters. Additional discussion of this topic would be useful given that the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) supports borderlands research, including the workshops and conference that generated chapters in this book. Pat Rubio Goldsmith observes that funding can create pressure to carry out research of interest to the US government, especially in support of security policies. He notes that of the $15 million DHS gave to the University of Arizona for border studies, more than 98 percent supports security concerns, while less than 2 percent support “the human angle.”

Uncharted Terrains concludes with a “Personal Code of Ethics for Border Researchers” which focuses on personal integrity, valuing research participants and research excellence. Taken as a whole, the articles in this volume provide powerful examples of the close relationship between research and ethics. The case studies and insights into immigration, social justice and research methodologies will be valuable not only for scholars working the borderlands but for those working in any region of conflict. Given the scope of violence at the borderlands, however, in places the book seems too concentrated on the process of conducting research and not enough on critical analysis of the violent impact of border policies. Significant research, much coming from the University of Arizona, does address the state’s role in border violence. The work of Raquel Rubio Goldsmith et al. to document border deaths and their causes, Robin Reineke’s attempts to identify those who have died and to examine the policies causing so many migrant border crossers to remain unidentified and the research of Jeremy Slack and his colleagues on the dangers and family separations caused by deportation policies are simultaneously examples of academic and human rights research (9). These projects are particularly relevant in a political environment where the suffering resulting from economic and enforcement policies is ignored or justified in the name of security.

***

Rather than focusing on the ethics of border research, When I Wear My Alligator Boots reveals the power of ethnographic work to addresses the often invisible inequalities embedded in the war on drugs in both the United States and Mexico. The ethnography opens with a description of low-wage work under Mexico’s desert sun, with the author as a volunteer alongside five men who are clearing weeds for $10 a day. Residents of the community engage in other types of intermittent low-wage labor, including fishing, selling tamales and caring for an elder. The low pay, lack of social security and limited possibilities for upward mobility are central themes of the ethnography. Given this context, Muehlmann is not surprised to learn that Andrés, one of the men in the weed-clearing work crew, switched from odd jobs to selling drugs, one of the few possibilities for earning higher wages and achieving upward mobility. She observes his transformation, including his wearing alligator boots—the sign of a real narcotraficante, someone tells her, and the source of the ethnography’s title. Muehlmann discusses the prestige, pride and defiance that can come from narco-culture and that get celebrated in narco-corridos drug ballads popular in northern Mexico.

An anthropologist at the University of British Columbia, Muehlmann didn’t set out to study narco-trafficking in northern Mexico. She attempted to avoid the topic in her initial fieldwork on water scarcity, noting that dozens of journalists had been killed for publishing on the drug trade. Yet people approached her to discuss the issue, and “in the end,” she states, “it was not up to me whether to pursue the topic: people came to me with their stories.” Her book focuses not on high-level narco-traffickers who earn the greatest profit, but rather on the “ordinary” people—those who carry drugs and money across checkpoints and serve prison sentences—and the women whose sons or partners are in prison.

When I Wear My Alligator Boots centers on a small number of residents in “Santa Ana,” the pseudonym that combines villages in Mexico’s northern desert. Muehlmann carried out long-term participant observation in the region, observing daily life and conducting interviews with residents over a period of several years. Andrés, the man from the work crew who becomes involved in the drug trade, goes to prison for years when he is caught. Upon his release, he initially refuses to return to narco-trafficking but, finding his options limited, returns to smuggling. Muehlmann describes the impact of Andrés’ imprisonment on his mother, who brought her last pesos to pay off the prison to prevent the mistreatment of her son. Muehlmann highlights the impunity and complicity of Mexico’s government officials with narco-traffickers; the most powerful leaders of the cartels bribe officials and rarely go to prison, while low-level workers in the drug trade, such as Andrés, are much more vulnerable. She writes of Cruz, a drug addict, illustrating how the increase in the flow of drugs through Mexico, coupled with the increase in local production of manufactured substances such as methamphetamines, has led to increased addiction in Mexico.

Among the book’s many strengths is the way Muehlmann challenges misperceptions of the war on drugs in Mexico and the United States. Through ethnographic detail, she shows how the lines are blurred between “legal” and “illegal” and between those who are “involved” and “not involved” in drug trafficking. She tells of a taxi driver who gives rides to those involved in the drug trade and of military officials who protect family members by failing to turn them in for possession, raising questions about whether such individuals should be considered part of the drug trade.

A fascinating chapter on money laundering addresses the ways drug profits infiltrate the banking system, becoming part of global capitalism. Muehlmann recounts how residents of Santa Ana assist in transferring money to bank accounts opened by Don Emmanuel, a money launderer. Having a number of small accounts allows him to “store” money undetected, since deposits under a certain amount do not have to be reported by banks. Billions of dollars of drug money is laundered through financial institutions in Mexico and the United States; the international bank and financial services giant HSBC paid a $1.9-billion settlement to the Justice Department for laundering in 2012. Muehlmann cites a former head of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, who observed that during the 2008 fiscal crisis the profits of organized crime were some of the only “liquid funds available” when speculative capital crashed, meaning that some banks were rescued, at least in part, by drug money.

Muehlmann powerfully connects Mexico’s rural economy to the broader economic policies of the region, including NAFTA, and to the politics of the drug war in the United States and Mexico. Under NAFTA, trucking between the US and Mexico increased legal trade and created opportunities for drug smuggling on the same routes. Many farmers, unable to compete with the highly subsidized corn and other crops that flooded Mexico’s market following NAFTA, were put out of business. Some migrated to the US and some, as Muehlmann notes, attempted to make a living in the drug trade.

The risks of the drug war are distributed along class lines—the poor are criminalized both in Mexico and the United States. A better term for the war on drugs would be the war on the poor. Yet its risks are distributed also along national lines, with Mexico paying the highest costs. “For while Mexico exports the drugs and profits to the United States,” writes Muehlmann, “the United States exports the guns, the bloodshed, and the blame to Mexico.” In a similar manner, security policies emanating from the United States criminalize undocumented migrants, while employers profit from low-wage labor, consumers gain access to low-price commodities and private prisons and military contractors profit from detention and militarization.

Significantly, these books not only document the impact of criminalization but also provide a glimpse of possible alternatives. Just as repressive policies cross borders, so do hope, resistance and struggles for transformation. Mexico’s Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity, which challenges the violence of the drug war, is but one example. Family members who lost loved ones in this violence spoke out and shared their stories in Mexico and the United States in 2012. Perhaps, as Pat Goldsmith observes in Uncharted Terrains, “Telling the stories of the oppressed holds a promise of envisioning a different, more just reality.”

Notes

1. Wendy Brown, Walled States, Waning Sovereignty (New York: Zone Books, 2010).

2. Maria Jimenez, “Humanitarian Crisis: Migrant Deaths on the U.S.-Mexican Border” (San Diego: American Civil Liberties Union of San Di- ego and Mexico’s National Commission on Human Rights, 2009).

3. Christine Kovic, “The Violence of Security: Central American Migrants Crossing Mexico’s Southern Border.” Anthropology Now 2, no. 1 (April 2010).

4. For example, see Christine Kovic “Searching for the Living, the Dead, and the New Disappeared on the Migrant Trail in Texas” (Houston: Houston United, 2013). http://prtl.uhcl.edu/portal /page/portal/HSH/Anthropology/migrant%20 deaths%20report%20edited%207%2015.pdf.

5. Website of US Customs and Border Protection, Falfurrias Station. http://www.cbp.gov/ border-security/along-us-borders/border-patrol -sectors/rio-grande-valley-sector-texas/falfurrias -station. Accessed July 30, 2014.

6. Raquel Rubio-Goldsmith, M. Melissa McCormick, Daniel Martinez and Inez Magdalena Duarte, “The ‘Funnel Effect’ and Recovered Bodies of Unauthorized Migrants Processed by the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner, 1990–2005, Report Submitted to the Pima County Board of Supervisors (Tucson, AZ: Binational Migration Institute, 2006).

7. Ruth Gomberg-Muñoz, Labor and Legality: An Ethnography of a Mexican Immigrant Network. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

8. Jorge Bustamante, “Immigrants’ Vulnerability as a Subject of Human Rights,” International Migration Review 36 (2002).

9. Raquel Rubio-Goldsmith et al. “The ‘Funnel Effect’ and Recovered Bodies;” Robin Reineke, “Lost in the System: Unidentified Bodies on the Border.” NACLA Report on the Americas 46(2013); Jeremy Slack, Daniel E. Martinez, Scott Whiteford, and Emily Peiffer, “In the Shadow of the Wall: Family Separation, Immigration Enforcement and Security,” (Tucson: Center for Latin American Studies, University of Arizona, 2013). http://las.arizona.edu/sites/las.arizona.edu/files/ UA_Immigration_Report2013web.pdf

Christine Kovic is associate professor of anthropology at the University of Houston–Clear Lake. She has conducted research in Mexico and the United States in the field of human rights for the past 20 years. Her current research addresses the intersection of human rights and immigration, with emphasis on Central American migrants crossing Mexico in the journey north and on the human rights and organizing efforts of Latinos in the United States. She supported the foundation of the South Texas Human Rights Center to promote policies, laws and practices to prevent migrant deaths in the context of border militarization (http://southtexashumanrights.org).