On March 5, 2015, Eve M. Kahn’s “Newsworthy Notes” in the Antiques section of the New York Times included an announcement for a local auction alongside two short articles, “Remembering Ragtime” and “Go raise a glass” [1].

“Art of Internment Camps Will Head to Auction” was the first public announcement that the Rago auction house in New Jersey would be auctioning off about 450 artifacts made by Japanese-Americans during World War II. The objects were fashioned in the internment camps by individuals incarcerated for having Japanese ancestry, a majority of whom were American citizens. The article noted that the collection “was assembled by Allen Hendershott Eaton, a crafts expert who analyzed it in his 1952 book, Beauty Behind Barbed Wire: The Arts of the Japanese in Our War Relocation Camps. When he tried to buy pieces from the internees, he wrote, ‘They offered to give me things to the point of embarrassment’” [2]. This short news article discussed the pieces and the internment itself, and provided information about the auction. As an American of Japanese ancestry whose family had been interned, I was interested in the collection and its stories.

History on the Auction Block

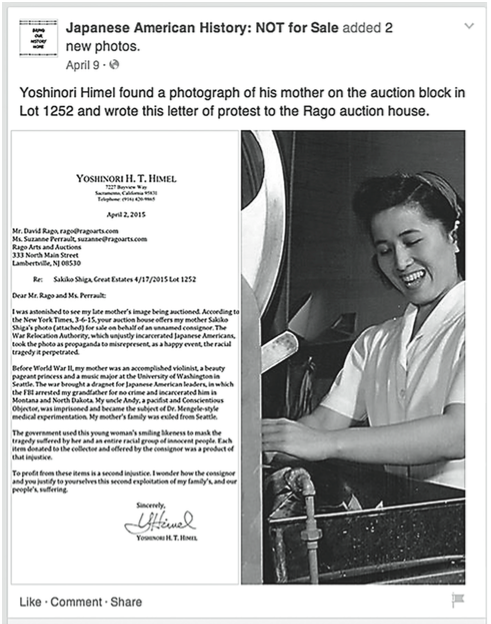

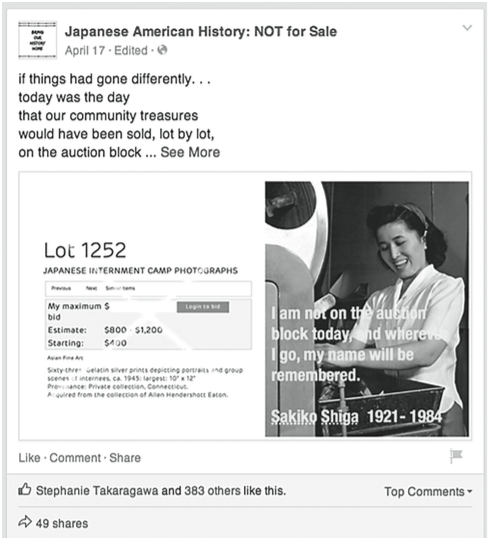

The types of things made in the internment camps were not of significant monetary value. They were primarily items such as flower vases, sculptures, name plates and brooches carved out of wood by non-artisans trying to create a more comfortable and normal life. For the entire lot of 450 artifacts, the high bid estimate was less than $28,000. Also included for auction were photographs of internees and some paintings done in the camps. Because internees were not allowed to have cameras due to the fear that they were spies, paintings and drawings often serve as the only record of the early days of the camps. Photographs that do exist, such as those in the auction, were made for propaganda purposes and show “happy” internees. This was the case for a photograph identified by Yoshinori Himel [3], who found an image of his mother up for auction.

The artifacts are of significant historical if not monetary value. During WWII all people of Japanese ancestry who lived on the West Coast were rounded up and placed in 10 internment, relocation or concentration camps, depending on who is talking and when. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called them “concentration camps,” but after knowledge of Nazi concentration camps spread, the terms “relocation” and “internment” became more common to avoid the comparison. Sixty-five percent of these estimated 120,000 individuals were American citizens, then called “non-aliens” by the US government. Most of the people interned were given only a few days’ notice that they would be moving, often with little understanding of where they would go and for how long. People sold their cars, homes, businesses and belongings for a tenth of their value in order to recoup something for an unknown future. The internees were only allowed to bring “what they could carry,” although they were required to bring bedding, utensils and clothing, leaving little room for anything beyond the bare necessities. Internees were sentenced to live in “barracks” which were so hastily constructed that the wood was not fully dried and cured. Within months it shrunk down to reveal gaps in the floors and walls, with the knot holes falling out. There were no walls to divide the open 120-foot space between families and no running water. Wood-burning stoves were the only heat source and each area was given a single light bulb for illumination. Under these conditions there was no privacy, no security and a complete breakdown in the normalcy of everyday life. Latrines were shared among each block of barracks, but no walls or partitions were offered between toilet or shower stalls. These are the images from which history books have shielded the American public, focusing instead on the more palatable photos in Ansel Adams’ book on the internment camp Manzanar, Born Free and Equal [4].

A History Repressed

Much of the history behind the objects and images in the Rago auction has also been hidden within the Japanese-American community. I learned about the internment in high school, and when I asked my family, they always found polite but firm ways to steer the conversation in other directions. “Shikata ga nai,” often translated as “it can-not be helped,” was frequently used to explain why few people discuss the internment. I soon learned that this was a common response among the interned, as this history was viewed as shameful, and those who lived through it hoped to forget.

The Rago auction was set for April 17th. On April 11, I received the following email:

Hi all — please visit and “like” this new FB page — just launched — which protests the April 17 sale by Rago auction house of Japanese American heritage items, including crafts, personal objects and prisoner artworks that were made by our ancestors and family members held behind barbed wire during World War II. We think that it will grow quickly in the next several days. People are still learning about the sale and are very upset.

https://www.facebook.com/japaneseamericanhistorynotforsale

We are asking that the Rago auction house remove these lots from the auction. They were given (not sold) to the original collector, who opposed the incarceration, in the expectation that they would be exhibited. Now the collection is primed to be sold and dispersed into private hands against the collector Allen Eaton’s stated wishes. We hope that Rago will consider the anguish and anger that the community feels and realize the mistake they have made in attempting to sell our cultural property and, in so doing, profit off this tragic history.

Please pass this on to your friends and write to David Rago at rago@ragoarts.com and Suzanne Perrault at suzanne@ragoarts.com

A community letter will be written to the firm in the next few days. The attachments below will be added to the FB page.

I’m a member of an ad hoc committee that sprang up in the last week to address this fast-developing issue.

Gambarimasho [5]

Nancy, member

Ad Hoc Committee to Oppose the Sale of Japanese American Historical Artifacts

That same day a Facebook page called “Japanese American History: NOT for Sale” was launched by Saya Russell, a yonsei (fourth- generation Japanese-American) in Los Angeles, and her mother, Nancy Ukai Russell, a writer in Berkeley.

Through various repostings, taggings and the site’s newsfeed, more people were soon drawn into a common discussion and given a place to voice their common concerns. The page was set up to provide information about the auction and reasons it should be stopped. It included descriptions of many objects but also provided alternative information that was not available in the Rago catalog, such as personal stories that had been recovered though research on the artifacts.

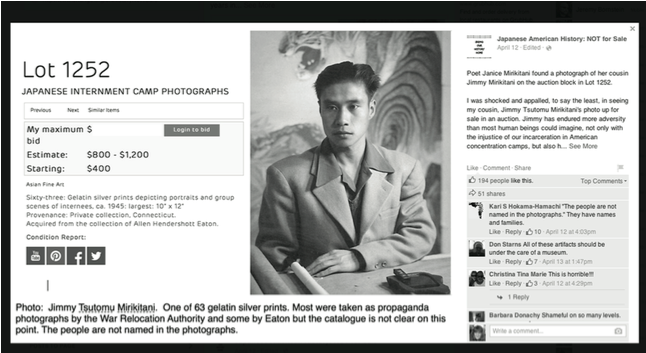

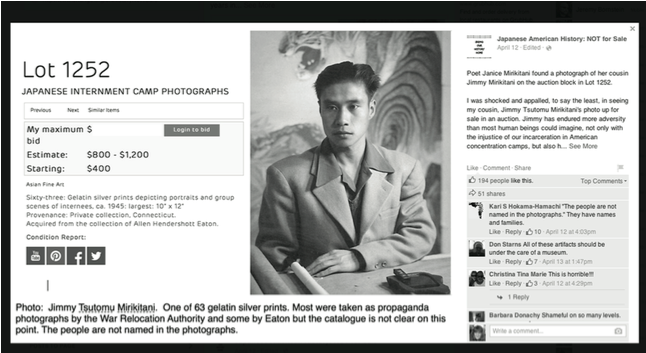

Lot 1242, 63 gelatin prints valued at $800–$1200, included this image of Jimmy Mirikitani, which was posted to Facebook accompanied by this statement by Janice Mirikitani, Founding President, Glide Foundation, and Second Poet Laureate of San Francisco:

I was shocked and appalled, to say the least, in seeing my cousin, Jimmy Tsutomu Mirikitani’s photo up for sale in an auction. Jimmy has endured more adversity than most human beings could imagine, not only with the injustice of our incarceration in American concentration camps, but also his struggle for validation as an American citizen. He was homeless for years in the streets of New York, living off of the sale of his art work. I had the honor of participating in a documentary about his life and his art, The Cats of Mirikitani, which respectfully revealed his journey of perseverance and dignity.

To ‘pimp’ the suffering of my family, my community is not only insulting, it is inhumane. I was as an infant incarcerated in a camp in Rohwer, Arkansas, so I have my own personal journey witnessing the after- math of the camps on my mother’s life.

Do not commit this travesty of cheapening and ‘selling’ memories of cherished family members, and artwork which was created to survive the isolation and humiliation of the camp experience.

Social Media: Public History and Community Forum

Facebook provided a platform for people to engage, interact, share stories and share viewpoints. It became a nexus of individual histories that led to a community history. Perspectives, information and ideas about the auction and how to stop it were brought forth from Japanese-American internees, their families and allies. In contrast to early silences about this history, the stories about the internment as a violation of civil rights came rushing to the fore in this Facebook forum:

There are many of us who are not of Japanese American heritage who feel this is unjust in every way, even the thought of it.

This is a slap in the face of not only the Japanese people but all races who have been victimized by the known world abusers.

Are photos or info the works posted online? [This received a quick response with a link to the online images.]

Thank you, Reverend Bob, for speaking out against this shameful situation. As you know, our family was displaced and lost everything while incarcerated. For this kind of profiteering to take place, it’s a further slap in the face after all these years. Where and when does it all end?

‘The people are not named in the photographs.’ [But] they have names and families.

All of these artifacts should be under the care of a museum.

Does anyone know if the Japanese American National Museum has been contacted? Th[ese] art works are priceless.

How can we stop this. Why isn’t the national media involved or [is] the Hillary campaign considered more important?

These comments are drawn from the first few posts on the Facebook page. People posted for a variety of reasons: to gather more information, offer solutions, express opinions. But one thing is clear: people were, and are, talking to each other. Though often seen as one-way communication, Facebook became a fully interactive community forum. I read through the posts repeatedly, shared and “liked” the comments, and found myself being educated on different perspectives, ways these artifacts were being viewed and how they had become the vehicle for a much more significant conversation about US history.

Community blog posts and local Asian American organizations such as AsAmNEWS and AsianConnections [6] posted within hours of receiving the email, using as many platforms as possible to reach a wider audience quickly. These sites also pointed to the Facebook page as the primary source of information, driving more visitors there and generating more conversations. Also included on the Facebook page was a link to a Change.org petition titled “Negotiate in good faith with the Japanese American community to preserve American concentration camp artifacts.”

With a few days left before the auction, the Change.org site had collected thousands of signatures. More compelling, however, were the accompanying statements. Unlike Facebook, which became a forum for information-seeking, questions and suggestions, the Change.org site featured a comments section for signatories. Here individuals gave much more personal accounts of their families and experiences. These came in the form of testimonials, evidence of the incarceration and its effects. People wrote about histories of loss and dignity, freedom and livelihoods. The outpouring of support on the Change.org site was stunning and revealed deeply affected personal histories. The power of these stories brought out more stories — more than 300 pages — strong narratives of individuality and collectivity that invited similar responses. I read through hundreds of these stories, hearing similarities that mirrored my own experiences about how much of this history was never revealed to the families themselves. However, these stories were being told more recently through the Japanese American National Museum and historic sites such as Manzanar and the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation [7], which were also represented on the Facebook page. One signer wrote:

My family was wrongfully incarcerated during WWII at Minidoka, along with thousands of others. They, like so many, lost everything and the effects of this injustice have lasted for generations. This is not ancient history; the art and artifacts so coldly being sold at auction have ties to people and families in the present. People are looking at PHOTOS of their family members, art that their parents created, hand carved signs that hung outside their barrack doors, being sold to the highest bidder while ripping open the barely healed wounds of the hurt and betrayal that they have suffered at the hands of their own country. These items were given with the intent that they would be preserved and shared as a part of history in an exhibit, so that we may remember the wrongs of our nation’s past and never allow them be repeated again. If the intent is no longer to preserve them for the public they should be returned to the families that they belonged to. I’m absolutely disgusted that the Eaton family should wish to exploit those who have suffered and survived so much to sell off these items to the highest bidder and profit off of the pain of my family and our community. Have we not suffered enough?

And a few minutes later:

I am a fourth generation Japanese American whose parents and grandparents lived through the incarceration during WWII. Had there not been places like the Japanese American National Museum I and countless others would not know about so many facets of our history. These priceless artifacts belong in a museum for the public to learn from. Please take these off your auction. Thank you.

And within an hour:

My mother is nearly 83 and was incarcerated in Tule Lake and Heart Mountain as was her whole family — except her brothers who served in the US armed forces. These items need to be publicly displayed, not privately bought and kept. Please respect the wishes of Mr. Eaton and the ever-dwindling number of people like my mother who experienced this first-hand.

These comments now number in the thousands, representing many individuals who placed their stories into the public sphere and in the process revealed an elusive truth. As the petition and Facebook site drew more attention, mainstream media and sites not specific to Asian American and Japanese American issues picked it up, including ABC, the New York Times, the Sacramento Bee, the San Francisco Gate and CNN.

The initial response from the auction house was grim. Eva M. Kahn, who wrote the first story in the New York Times, followed up on April 13:

A spokeswoman for Rago wrote in an email that the unnamed auction consignor, who knew the Eaton family, is ‘not in a financial position’ to donate the material to institutions and did not feel qualified to choose one institution over another.’ The consignor has described the protests as a ‘social media attack’ meant to ‘bully us into compliance with their demands.’[8]

The response from the community on Facebook was quick:

The sale of items of deep personal value on a cold and indifferent open market is reminiscent of the humiliation that our families had to endure when they were first incarcerated. American citizens of Japanese descent were ordered into camps and only able to bring what they could carry in their hands. This forced them to hurriedly sell most of their precious personal items. The auction is an insensitive replication of this trauma that all of our families were forced to live through. Going through with this auction is emblematic of the same brutal insensitivity that characterized the original order to incarcerate our families.

The Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation stepped in and offered to buy the lot for $50,000, almost twice the high estimate for the items. The seller claimed that he wasn’t sure if this was the “right” organization for the lot and was assured by the auction house that many other institutions would be present at the auction. Speculations from the community were that the auction house was now intending to use the publicity and outrage to spark a bidding war among community members and institutions.

Two days before the date of the auction, Rago suddenly agreed to pull the lots that included Eaton’s collection. Activist and actor George Takei entered negotiations with the Rago auctioneers while on a trip to Australia. Takei, most famous for his role as Sulu on the original Star Trek television show, was interned at the age of five at a camp in Rohwer, Arkansas. He and his parents were American citizens. His role in promoting awareness of the internment is clear in his work with the Japanese American National Museum and other Asian American organizations and his Broadway musical Allegiance, which is set during WWII in a Japanese-American internment camp and scheduled to open on Broadway in late 2015.

NPR’s news segment “Art from JA internment camp saved from auction block” included comments from Holocaust historian, Marc Masurovsky, who drew parallels to paintings Jewish families lost during WWII [9]. And in a May 7, 2015 post on the Brooklyn-based, hipster arts and culture blog hyperallergic.com, Aaminah Shakur asked, “Who are the rightful owners of artifacts of oppression?” It was clear that the issue reached beyond Japanese-Americans. The community response was again well documented on Facebook:

Wow. Assuming this is a confirmed report, this is what can happen when a community unites and mobilizes!

Yay!!! I am so proud to know that I played a small role in making this happen. Everyone that signed the petition or passed the story on through social media should be proud of themselves. What an awesome victory!

Can’t believe it — the power of the people!

Thank you George Takei! Would also like to thank Rago and the consignor for doing the right thing and hopefully something can be worked out.

These and hundreds of other comments from across the country and around the world can still be seen both on the Facebook and Change.org sites.

Little Tokyo No More

As a museum anthropologist, my research focuses on how museums and memorial sites help to construct collective memory and identity. My dissertation on the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles explored how collective memory for a community can be defined and exhibited, and ultimately reproduced as community narrative. I am also interested in Japanese-American communities in Southern California, a task that 50 years ago would have been primarily a matter of geography. In their heyday, there were more than 50 “Little Tokyos” and “Japantowns” throughout the United States, with a heavy concentration on the West Coast. Today there are only three, in Los Angeles, San Jose and San Francisco, which are largely tourist districts and no longer house the community as they once did. While these are great places to shop and eat, it is no longer possible to find what I had been taught to define as a distinctive Japanese-American community there. Most of the scholarship I cut my teeth on taught me that communities require face-to-face contact, sharing food, ritual, values, language and, most importantly, space. When I began to look for that community in 2014, I realized it was geographically dispersed, leaving me to look for other ways it might now be configured.

A 2012 PEW study [10] noted that Asian Americans were the most Internet savvy and upwardly mobile demographic in the United States. However, this study was limited only to English-speaking Asian-Americans, which eliminated a significant number of immigrants. The findings should not be seen as a reflection of Asian America overall, but rather the educated and assimilated population. I imagined that this wired demographic would certainly use the Internet to create its own communities, and I set out to find my own Japanese-American community online. Starting with the college students with whom I worked every day, I began my research into contemporary Japanese-American communities online. Enlisting students who spent the majority of their free time using social media sent me in various directions such as YouTube (WongFu productions, Michelle Pham and Ryan Higa), Facebook (You know you’re Japanese American when) and a series of community-based non-profit sites, but these were primarily places to watch or learn about community rather than interact with one. I was disappointed that I was unable to find a community of people like myself, Americans of Japanese descent, who could discuss issues of our identity or community online.

When I received that first email about the Rago auction and went to the Facebook site and the Change.org petition, I read through the discussion and realized that I agreed with many comments. There were also points of view I had not considered, and while I might not necessarily agree, they provided very important contributions to an evolving debate. On these sites I found both support for the Japanese-American experience and history and a resounding response that defied the model minority stereotype. This response was multivocal, in a forum where all could contribute their thoughts and not always agree. The people who posted on Facebook and Change.org used these spaces to articulate their own identities, constructing a common community. I was so caught up that I did not immediately realize this was precisely the community I had been seeking. It was the cause that was strongly tied to the history of the community, a history most clearly articulated in public spaces such as the Japanese American National Museum, which revealed the individuals who still strongly shared specific aspects of their identity and were putting all their stories out there.

When I first read the New York Times article about the Rago auction, I went immediately to the site to see what was for sale. As both a scholar of Japanese American history and someone whose family is part of that history, my first response was to bid on the items. They were not terribly expensive, but more than I would ordinarily pay for just about anything and somewhat beyond the range of an assistant professor’s salary. Yet I felt these were important documents of history that would be better appreciated by someone personally connected to Japanese-Americans and their cultural institutions. Once or twice, it occurred to me that I should ask my family what they thought about the auction, but then I decided I might just leave that be, rather than risk discussion of a taboo topic. That was about as far as my thinking went, but I bookmarked the site, logged the auction date in my calendar and even found out how to absentee bid.

It wasn’t until I received the “stop the Rago Auction” email that I understood my conflict. I had not considered this in a very sophisticated way. I was thinking as an individual, not as part of a community. Perhaps this was revealing of my own cultural patterns as Japanese-American; a holdover of “shikata ga nai.” Yet it was the community that got up and fought and used this history to draw attention to the injustice they felt was being perpetrated on them again. This on-line community also educated its members by discussing different points of view about who has rights to this past. This model minority was not passive, but vocal, collective and indicative of the community I had been looking for all along. While we may have lost some physical terrain, the Little Tokyos and Japantowns, those who were involved in sharing stories, signing the petition, writing letters, interviewing and contacting others were all participants in constructing a new, virtual community that stretched across international borders. These thousands of individuals of diverse backgrounds, whose collective voice illuminated a part of American history, shared and created a common bond that can only be called community.

While the items have been taken off the auction block and will now be received by the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, the debate is not over. This community has multiple voices and obligations and the discussion over where the objects belong will continue to foster a dialogue among many people, dispersed over many places.

Notes

1. Eva M. Kahn. “Art of Internment Will Head to Auction.” New York Times, March 5, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/06/arts/design/ art-of-internment-camps-will-head-to-auction.html?_r=0, accessed June 23.

2. Eva M. Kahn. “Art of Internment Will Head to Auction.” New York Times, March 5, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/06/arts/design/ art-of-internment-camps-will-head-to-auction.html?_r=0, accessed June 23.

3. Yoshinori Himel is a retired civil lawyer from Sacramento. He is married to Barbara Takei, who is co-author of Tule Lake Revisited: A Brief History and Guide to the Tule Lake Concentration Camp Site, second edition (2012).

4. Ansel Adams. Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal Japanese Americans. (New York: U.S. Camera, 1944).

5. Often spelled ganbarimashou, this word loosely translates to “let’s do our best together,” or more colloquially “hang in there.”

6. AsAmNews is a website dedicated to documenting the Asian American experience and showcasing its depth and diversity including a full roundup of headlines about the Asian American community from both mainstream and ethnic media. AsianConnections is a blog about and for the Asian American community.

7. The Japanese American National Museum is located in downtown Los Angeles in the historic Little Tokyo district. Manzanar and Heart Mountain are two of the 10 internment camp sites. Manzanar is located in the Owens Valley in California, about four hours north of Los Angeles. Manzanar is operated by the National Park Services and is a National Historic Site. Heart Mountain internment camp is located near Cody, Wyoming and is operated by the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation.

8. Eve M. Kahn. “Auction of Art Made by Japanese-Americans in Internment Camps Sparks Protest” April 13, 2015. http://artsbeat.blogs.ny times.com/2015/04/13/auction-of-art-made-by-japanese-americans-in-internment-camps-sparks-protest/?_r=0 accessed August 2, 2015.

9. Wang, Hansi Lo. Art From Japanese-American Internment Camps Saved From Auction Block. NPR (April 16, 2015). http://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2015/04/18/400052232/auction-of-art-by-japanese-americans-in-internment-camps-cancelled accessed August 2, 2015.

10. Pew Research Center. “The Rise of Asian Americans.” June 19, 2012. Washington, DC. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2012/06/19/the-rise-of-asian-americans/

Stephanie Takaragawa is assistant professor of sociology at Chapman University. Her research and teaching focus on visual culture, with specific emphases on museums, art and media. Her dissertation Visualizing Japanese-America: the Japanese American National Museum and the Construction of Identity examined the role of the Japanese American National Museum in the construction and dissemination of a Japanese-American identity. She is part of the Ethnographic Terminalia curatorial collective and president of the Society for Visual Anthropology, a subsection of the American Anthropological Association.