As film making and viewing increasingly become identified with digital media — storage in bits and invisible streams that manifest as cinematic experiences in our classrooms, theaters and living rooms — it is easy to lose track of the concrete materials, processes and spaces that make these viewing experiences possible. Easy, that is, unless your job requires exactly that, keeping track of the many and varied materials that exist behind the scenes of a large and growing film catalog. This has been one aspect of my job since 2011, when I started at Documentary Educational Resources (DER), one of the most historically important resources for ethnographic film in the world today. I started with the belief that my role would be to bring DER into the age of digital, networked media, and I was quickly drawn into another world entirely. It is a world of 16 mm and 35 mm film elements in cans — camera originals, preprint materials and projection- ready distribution prints — sound recordings, production logs, journals and tape masters in every format imaginable.

The DER catalog includes over 850 titles, spanning nearly 100 years. Most notable is a body of ethnographic films made between the 1950s and 1980s, significant for establishing the field of ethnographic film, and including classics such as N!ai: The Story of a !Kung Woman, The Ax Fight and Dead Birds. While best understood today as historical documents rather than films of contemporary cultures, many continue to be used extensively in the classroom. For example, in the fall 2016 semester, N!ai was “played” 2,712 times on just one of multiple streaming platforms, a count that doesn’t include classroom and library viewing on DVD. In addition to these “classic” ethnographic films, shot largely on film, we have a growing collection of works shot on various digital formats, such as Poto Mitan: Pillars of the Global Economy, (un)veiled: Muslim Women Talk About Hi- jab, Framing the Other and Stori Tumbuna: Ancestors’ Tales, which have also become mainstays of college teaching. And each year we add approximately 20 new titles to our offerings, reflecting the work of filmmakers and anthropologists who have carried this tradition forward and applied it to contemporary social issues and events. For each film we distribute, DER maintains master materials. These may be original versions of films made on celluloid now held in an archive, tape masters or digital files.

Each film offers an irreplaceable window into culture and history, valuable not only for students and researchers, but also for descendants of the communities whose lives are documented — a value recognized, for example, by the 2009 induction of John Marshall’s 50-year film record of the Ju/’hoansi bushmen into the UNESCO Memory of the World Register. The outtakes, unreleased cuts and ancillary materials that DER and our partner institutions hold for many films are resources for understanding the origins of the field and informing contemporary scholarship and production. The DER archive provides a foundation for understanding the tradition of ethnographic media production, distribution and education and extending the practice into the 21st century. To keep these films available in high quality over many decades requires considerable time and effort, as well as access to expertise in archiving and in contemporary and historical production processes and forms.

Documentary Educational Resources

Neither a preservation facility nor merely a film distributor, Documentary Educational Resources (DER) occupies a unique position in the ecology of ethnographic film institutions. The organization was founded in 1968 by John Marshall and Timothy Asch, and incorporated as a nonprofit educational organization in 1971, to support their efforts in creating films for documenting, researching and learning about human behavior. Marshall and Asch took on the work of distribution because the existing distribution companies were ill suited to the short, experimental sequence films they were then making.

DER was one of several institutional centers set up worldwide to preserve, archive, study and distribute works of ethnographic film in the mid-20th century, including both film archives and university programs established to teach and research in ethnographifically informed cinema.

Of local significance for DER is the Harvard Film Study Center (FSC), established in 1957, under the direction of filmmaker Robert Gardner. FSC was founded to support film efforts associated with Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, which, along with the Smithsonian Institution, had sponsored the Marshall expeditions to the Kalahari in the 1950s. The Hunters, released in 1957, was one of the first films produced by FSC, with Marshall and Gardner working together on editing, and was followed by Gardner’s Dead Birds in 1964. Tim Asch began working with Marshall and Gardner at the Film Study Center when he was hired to edit the Ju/’hoansi (also known as the !Kung) “bushmen” footage under their direction. Differences in filmmaking styles began to emerge and, in the early 1960s, Marshall and Asch left the Film Study Center and subsequently founded DER.

In the late 1970s, Asch went to Australia and then on to lead the Center for Visual Anthropology at the University of Southern California in 1984, where he stayed until his death in 1994. DER remained Marshall’s production space until his death in 2005 after a career culminating in the 2001 release of A Kalahari Family, his five-part, six-hour series on changing subsistence, politics, development and issues of representation that emerged over the 50 years during which he was engaged in the lives of the Ju/’hoansi.

Professionalization of Ethnographic Film

While iconoclasts such as Edward Curtis brought still and moving cameras to the field as early as the 19th century, it was the mid-20th century that saw ethnographic film established as a genre with distinct styles, schools and auteurs. Marshall and Asch, along with Gardner, Jean Rouch, Ricky Leacock and others, were part of a generation that embraced filmmaking as both cultural inquiry and record keeping. They brought poetic, activist and reflexive elements into their filmmaking and promoted the use of film in research and in the classroom. In the late 1950s and 1960s, filmmakers developed sync sound and portable cameras that could be taken into the field and operated by one- and two-person crews. This opened a new era of observational filmmaking. Opportunities for federal funding from the 1960s through the 1980s were also instrumental in the production of several comprehensive ethnographic film projects, both classroom and public oriented. For students and researchers, these included the Yanomamo films and Faces of Change series, and for television audiences, producer Michael Ambrosino’s Odyssey series, broadcast nationally in the United States on PBS.

Marshall and Asch are best known, respectively, for their films on the Ju/’hoansi Bushmen in Namibia and Botswana and the Yanomamo Indians in the Amazonian rainforest, which Asch produced in collaboration with anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon. DER’s founders, in fact, each produced a larger body of work. Among these are Marshall’s Pittsburgh Police series, which was a forerunner of today’s reality TV shows and a model for Cops, the longest running reality show in U.S. history, as well as his films If It Fits, about the declining shoe industry in Haverhill, Massachusetts, and Vermont Kids, which documents children’s play, made with researcher Roger Hart. Asch’s body of work includes the Jero Tapakan series about a Balinese spirit medium, significant for the ways the film’s subject is engaged in the making of the films. Asch also made films in Afghanistan, Uganda and eastern Indonesia and is known particularly for his close collaborations with anthropological researchers who specialized in the areas documented.

Through our work in distribution, DER has come to be the de facto steward of these and other films. In 1975, we expanded our distribution offerings to include the works of other filmmakers. Distribution of Sarah Elder and Leonard Kamerling’s On the Spring Ice and At the Time of Whaling, the first two titles in their Alaskan Eskimo series, was soon followed by their later works, including The Drums of Winter, which was inducted into the National Film Registry in 2006 [1]. DER also distributes the work of Robert Gardner, who established a poetic approach to ethnographic filmmaking through films such as Dead Birds and Forest of Bliss that is seen as precursor to today’s sensory ethnography. DER also distributes the Screening Room Series, a local Boston TV talk show, in which Gardner interviewed leading documentary and experimental filmmakers from Jean Rouch and Jonas Mekas to John and Faith Hubley, a reminder of ethnographic film’s close historical ties to other forms of independent filmmaking. The DER catalog has continued to grow as digital technologies have made filmmaking more accessible to anthropologists and others working in the tradition of ethnographic film.

DER’s Collections Management and Preservation Program

DER’s Collections Management and Preservation program is perhaps DER’s most important and least understood program. Our other programs — Curation and Distribution and Filmmaker Services — are more front facing and involve interacting daily with filmmakers, educators, museum and festival programmers and community members. As part of the Curation and Distribution program, we introduce new works to audiences; help exhibitors and educators identify appropriate titles for screenings, retrospectives and teaching; seek out reviews and ensure that the right film arrives in the right format and in time for a class or screening. In our Filmmaker Services program, we work directly with filmmakers on their current productions, consulting on fundraising, distribution and production and sometimes serving as fiscal sponsors. We participate in distribution events at film festivals and try to impart what we’ve learned about cross-cultural filmmaking and collaboration to a new generation of filmmakers. We also seek to serve as a bridge between the academic and filmmaking worlds through convening special events, such as the 2016 Film Pitch Session held at the American Anthropological Association meetings.

By contrast, the Collections Management and Preservation program operates behind the scenes and largely out of view of both filmmakers and audiences. It nevertheless entails a network of people and organizations connecting DER to archives and to individuals who hold the history of DER films as well as the technical knowledge and expertise related to ongoing maintenance of these materials. While Collections Management and Preservation is less visible, the physical labor and ongoing work of ensuring that audiences, today and in the future, have access to high-quality viewing experiences of these older films is very real indeed.

For each of the over 850 films we distribute, DER maintains access to master materials — this might be an original version of the film made on celluloid and now held in an archive, a tape master (such as Beta-cam or U-matic) or a digital file. Our work involves ensuring that these masters can be transformed into formats that meet the needs of diverse audiences and screening venues, from classrooms, museums and festivals to broadcasters and streaming platforms. In the past, this meant providing film prints, VHS and Blu-ray, but today universities and exhibitors generally want DVDs or digital files, and in some cases, 16 mm prints. This work entails not only having access to good original materials, but upgrading the versions in circulation as the technology changes. For example, in 2014, we invested in technology that would allow us to take standard definition videotapes and files and upgrade them to high definition (HD) to improve the quality of online streaming, screenings and exhibitions. A good system and physical infrastructure for preservation facilitates access, and it is only through access that the value of these works — whether for education, research or simply enjoyment — can be harnessed.

National Archives for Ethnographic Film

While DER has mainly been focused on the production and distribution of film works, the concern with preservation has always been an issue. The midcentury professionalization of ethnographic film, including production of landmark works such as the Ju/’hoansi and Yanomamo projects, were shaped by a concern with so-called “disappearing cultures.” It was believed these film records could be used as primary data for future research on extinct cultures as well as serving as records of the cultural practices for the communities documented. While anthropologists today focus on the ways in which cultures undergo change and communities persist, rather than thinking in terms of extinction, the films nevertheless have enormous value as documents of life prior to the rapid transformations brought on by incorporation into larger political and economic systems.

In October 1970, Gordon Gibson and Jay Ruby convened a three-day meeting in Belmont, Maryland, where the luminaries of ethnographic film, including Marshall, Asch, and Gardner, as well as Margaret Mead, Alan Lomax, Sol Worth and others, discussed plans for a national archive for ethnographic film. Attendees considered the potential functions of the archives, such as storage and cataloging of films and the archive’s role in the promotion of film as a research tool; acquisition criteria regarding both the types of materials (such as stills, sound recordings and videos in addition to films) and content matter (e.g., whether it would be limited to traditional anthropological subject areas or open to sociological works, documentation of urbanization and other issues); whether the new facility would include production studios; and policies about access, duplication and copyright.

In 1975, the National Anthropological Film Center (renamed the Human Studies Film Archives in 1981) at the Smithsonian Institution was created and began its mission to preserve, document and promote moving-image materials as an integral part of the anthropological record. Recently renamed the National Anthropological Film Collection (NAFC) in the National Anthropological Archives, today the NAFC offers state-of-the- art environmental storage, which remains the preferred strategy for long-term keeping of motion picture film, cool storage for interim safeguarding of magnetic media and a digital asset management system (DAMS) for digital files. Pam Wintle, the Senior Film Archivist at the NAFC, described these facilities as including an environmentally controlled minus-4-degree F subzero storage facility for film, in which the humidity is controlled by creating microclimates [2]. Another climate-controlled storage unit is kept at a temperature of 55oF and 30 percent relative humidity for videotapes and sound recordings. Because magnetic media is at high risk of loss due to obsolescence of equipment and physical decay of the analog carriers, priority is given to digital preservation of these audiovisual assets. Preservation digital video and audio files are ingested into the DAMS following best practices for maintaining the integrity of digital files over the long term.

The Ju/’hoansi and Yanomamo film collections were among the founding collection of the new national archive. The original 16 mm footage, outtakes and sync sound recordings for both were donated in the early 1980s, around the time of the completion of the first cold-storage facility. Subsequent donations over the next few decades included additional preprint materials, distribution prints, associated notes, logs, manuscripts, sound tapes and still photographs. The Smithsonian’s John Marshall Ju/’hoan Bushman Film and Video Collection today contains 767 hours of original film and video, 23 published films and videos, one video series and 29 unpublished films and videos, 309 hours of audiotape, 13.7 linear feet of papers and photographs, four original maps and over 100 additional maps [3]. The Yanomamo collection at the Smithsonian includes 93,000 feet, or 43 hours, of color film footage, including distribution prints of 21 edited films, another 12 rough-cut films, the outtakes, original field sound recordings and Timothy Asch’s papers and photographs [4].

DER and the NAFC now share over 25 projects, including the works of Jorge Prelorán, who pioneered the subgenre of ethnobiography with works such as Imaginero, Sam Low’s The Navigators and the Andalucian films of Jerome Mintz, for which NAFC provides expert archival inventorying, and preservation of film and supporting print materials, while DER maintains their accessibility to audiences.

The DER Vault

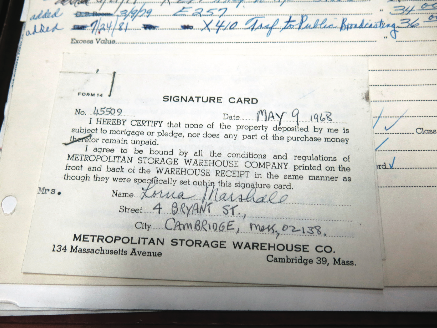

While the camera original and master materials for collections such as the Ju/’hoansi and Yanomamo films were donated to the Smithsonian decades ago, until 2015, DER was still offering safekeeping for a large amount of film materials. Long before the creation of a national ethnographic film archive, DER had established its own storage facility. In the 1960s, the ethnographer (and mother to John Marshall) Lorna Marshall leased a storage space at Metropolitan Storage, a local facility in Cambridge, Massachusetts, adjacent to the MIT campus. While it did not offer professional climate control, the massive brick and stone walls nevertheless maintained a near constant 50-degree F temperature and relatively constant humidity. And it was cheap. At the 1970 Belmont meeting, Tim Asch proudly shared with the attendees that he knew just how much storage cost, and that it was only $12/month. Over the next 40-plus years, the “vault,” as it was locally known, became a storage facility for not only the work of DER’s founders, but for a variety of films and filmmakers connected with DER, moving over time to larger and larger spaces.

As safe and convenient as Metropolitan Storage was, a dusty warehouse lacking control over temperature or humidity is not an ideal environment for long-term film storage. Film materials require low stable temperature and humidity control to reduce degradation. Of particular concern for contemporary cellulose- (rather than nitrate-) based films is vinegar syndrome, also known as acetate-film-base degradation. The National Film Preservation Foundation describes vinegar syndrome as follows:

“Its causes are inherent in the chemical nature of the plastic and its progress very much depends on storage conditions … The symptoms of vinegar syndrome are a pungent vinegar smell (hence the name), followed eventually by shrinkage, embrittlement, and buckling of the gelatin emulsion. Storage in warm and humid conditions greatly accelerates the onset of decay. Once it begins in earnest, the remaining life of the film is short because the process speeds up as it goes along. Early diagnosis and cold, moderately dry storage are the most effective defenses.” [5]

While Metropolitan Storage had been an adequate short-term solution, shortly after my arrival at DER, I became aware of the need for better temperature and humidity control and proper preservation of films. The materials remaining in the vault were aging and facing risk of deterioration. Some were already developing vinegar syndrome, so it was crucial that we move these materials into proper archival storage. With distribution hurtling toward digital media, it seemed at first quaint to be dealing with these materials from another era, and yet, as the project proceeded, the importance of the archive became clear and even more important. We had to complete the work of proper storage for our film materials to allow us to more fully embrace the future. For example, our decision to address the issue of a short-term storage solution that had become long term coincided with producer Norman Miller’s interest in digitizing and re-releasing the Faces of Change series, for which he needed access to the 16 mm film materials.

Emptying the Vault

In 2012, DER’s Director of Design and Media, Frank Aveni, with the help of DER staff, interns, friends and colleagues, began the work of inventorying and relocating the vault’s contents — a process that would take several years to complete. A preliminary inventory of the over 40 years of materials that had accumulated revealed we had close to 3,000 film cans. Fortunately, many cans and boxes were labeled with recognizable titles, many of them still part of the DER catalog, but others were mysteries: unreleased titles by Marshall or Asch, or works by their colleagues that had been entrusted to DER’s care. In addition, there were artifacts related to Marshall’s research — boxes of books on South African history, ethnographies, field guides and popular novels of the time.

Over the course of several months and numerous vault visits, Aveni identified the various discrete collections contained in the vault. The final inventory revealed original and preprint materials related to the Yanomamo films, all of the film materials for Marshall’s If It Fits, Vermont Kids, and the Pittsburgh Police series; the preprint materials for the Faces of Change series and the Odyssey series, and assorted distribution prints for films by Allison and Marek Jablonko, John Bishop and others. There was also a variety of previously unreleased works and footage that we are still researching. These include Marshall’s You Are the Problem, Wallace Rally, and Study of Violence, believed to focus on black power and the civil rights movement; One Day of Many, a documentary look at a day in the life of the McDonalds, a family of farmers from Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, made by Tim Asch; a film mysteriously titled Gary by John Marshall; and Morning Flowers, made as part of the Yanomamo series.

Then, with help from DER board member Karma Foley and former DER staff member Brittany Gravely, Aveni sketched out a plan for relocating the films into appropriate archives. In 2014, the remaining Yanomamo and Ju/’hoansi preprint materials were added to the NAFC collections. Footage from the 1976 Folklife Festival in Washington, D.C., which was shot by Marshall, was transferred to the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage; the film materials from Vermont Kids and If It Fits, two New England–based projects by John Marshall, went to the Harvard Film Archive; and assorted other materials were returned to additional archives or their owners. Among these was an internegative of Ben’s Mill, one of the Odyssey films, that ultimately was sent to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for preservation. These materials are now safely preserved in archives, and they are getting the best care possible.

The Work Ahead

The more I learn about these older film projects, the more I appreciate the significant work they represent for the field of ethnographic film and their relevance for today. For example, they offer models of collaboration between filmmakers and subjects, and between filmmakers and researchers, which despite today’s explosion of documentary filmmaking and sophisticated storytelling remain rare and overlooked. The depth of knowledge of the communities and cultures and long-term and intimate relationships with the individuals whose lives are documented in these films offer a standard of excellence to which contemporary filmmakers should aspire. The subject matter too still resonates. Marshall’s Pittsburgh Police Series takes on new significance as we struggle with contemporary issues of policing, particularly in light of racial incidents and the Black Lives Matter movement inspired by them. Vermont Kids offers a beautiful portrait of children’s play — from building forts to outdoor games — that is generating renewed interest in our screen-obsessed culture. Ongoing preservation and access is vital for these film classics and for the new classics produced on digital video.

It is an appreciation for the films in the catalog, and their ongoing use for teaching and exhibition, that motivates the hard work required to keep these films in circulation. Now that our celluloid film materials are in proper storage [6], we can turn our attention and energies to two other priorities for the Collections Management and Preservation program. The first, similar to the just-completed transfer of film to permanent storage, involves inventory and long-term preservation for our tape masters. DER holds more than 1,600 tape masters — mainly Betacam SP, U-matic and DVCAM, but also Digital Betacam and 1-inch and 2-inch tapes — that until recently served as our distribution masters or were in circulation for broadcast and screenings. In some cases, we know these tapes are the best-cared-for copy of a particular film, as we’ve had filmmakers contact us to create new masters when their own copy has been lost in a move, destroyed in a flood or damaged by some other calamity. Unlike film, tape is not ideal for long-term preservation, and ultimately our plan is to digitize and “up-res” (turning standard definition into high definition) the films, enabling both better screening experiences and more secure digital storage.

For our celluloid-based titles, we can now turn our attention to upgrading the films in circulation. For many of our older films, the transition to digital was made during an era of VHS tape and VCRs. Schools and other audiences made the transition in their viewing preferences quite rapidly. Without a budget or resources to transfer every film to video properly, many inexpensive and low-tech “one-light” transfers were made by recording the projection of a distribution print off of a screen or wall. This produced a copy with poor-quality image, often with improper framing, in which colors were dark or dull and fine details became muddled. Other films were transferred through a professional telecine process, where the film is passed in front of sensors that convert the image to a video signal in real time, producing a much higher-quality version. However, for many years, the resolution of this type of transfer was limited to standard definition by conventional tape formats, such as Betacam SP and Digital Betacam, which did not compare in quality to the projected 16 mm film.

In recent years, the development of high definition digital video has made possible a significant improvement in the quality of film-to-video transfers, retaining more of the inherent colors and contrasts of film stock, and the film-to-HD transfer equipment and services have become more common and affordable. Thanks to the rapid growth of computing power and storage capacity, modern scanners now output digital files scanned at 2K or 4K resolution while also improving the stability of the frame during transfer and thus reducing wobble and ripple effects commonly seen in old films.

In the past several years, DER has worked with a number of filmmakers who have returned to the archives and to their original film materials to retransfer or remaster the films using these new and newly accessible digital technologies. These include Root Hog or Die, a National Endowment for the Arts-funded film about farming culture in the hill towns of western Massachusetts and southern Vermont, which is now available for the first time on DVD; Neighbors: Conservation in a Changing Community about gentrification in Boston’s South End; A Weave of Time: The Story of a Navajo Family; The Drums of Winter; and the Faces of Change series.

Most recently, we were awarded a 2017 NFPF grant to preserve nine of the films from the Yanomamo series, including Magical Death and A Man Called ‘Bee’. In the coming years, we hope to continue to take advantage of these new technologies and invaluable federal funding, and return to our archives to remaster the remaining films in the Yanomamo and Ju/hoansi series (preservation work has already been completed for The Ax Fight, The Feast, and The Hunters with funds from the NFPF or the Smithsonian Institution, and were re-released years ago). We recently acquired distribution rights for a collection of films made by Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson, including Trance and Dance in Bali and the Character Formation in Different Cultures Series, and once we’ve located the best available film masters, intend to do such preservation and remastering work before releasing them on DVD and streaming.

For several years, the DER staff has been reflecting on the work we do and how to best articulate it as a set of formal programs. Until recently, we struggled with when and how it was appropriate to refer to DER as an archive and whether or not to call the work we did preservation. The Collection Management and Preservation program was born of these discussions and reflects work that DER had been doing for decades. We have come to understand that the work of preservation and access are two sides of a coin, each dependent on the other for their success and value. DER’s founders recognized this through their involvement in the founding of the NAFC. We look forward now to ensuring that a new generation has access not only to the films we consider classics today, but to the new classics that are emerging out of the contemporary period.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Frank Aveni, who led the effort to transfer DER’s film assets to suitable preservation facilities, for his input on this essay, including providing essential technical explanations. Thanks also to Jennifer Cool, who invited me to submit the article following our shared involvement in an American Anthropological Association panel for the Human Studies Film Archives 40th anniversary, for her guidance throughout.

Notes

1. DER, in fact, distributes several films that have been inducted into the National Film Registry. They include the following titles (with the year in which they became part of the Registry): Drums of Winter (2006), The Hunters (2003), Dead Birds (1998), All My Babies (2002) and Trance and Dance in Bali (1999).

2. For more information, see the links to publications on subzero storage for film and photographs on Wilhelm Imaging Research site, http://wilhelm-research.com/.

3. This does not account for all of the Marshall-related materials in the archives. For example, the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology at Harvard holds the entire Marshall expedition photo collection and additional journals and papers not specifically related to the films.

4. Jill Fri, Ann Hunt, and Yu-Ra Jung, “Finding Aid to the Papers of Timothy Asch,” Fall 2004, http://anthropology.si.edu/naa/fa/asch.pdf.

5. National Film Preservation Foundation, “Preservation Basics,” https://www.lmpreservation.org/preservation-basics/vinegar-syndrome.

6. With some exceptions! We still have an assortment of unidentified films and would be happy to connect with anyone who entrusted their film works to DER. If you left any film with DER, we would like to know and get it back to you.

Filmography

All My Babies, George Stoney, 1953.

The Ax Fight, Timothy Asch and Napoleon Chagnon, 1975.

At the Time of Whaling, Sarah Elder and Leonard Kamerling, 1974.

Dead Birds, Robert Gardner, 1964.

The Drums of Winter (Uksuum Cauyai), Sarah Elder and Leonard Kamerling, 1988, (digitally remastered 2015).

Faces of Change Collection, Norman Miller (producer), 1979–1983.

Framing the Other, Ilja Kok and Willem Timmers, 2001.

Imaginero, The Image Man (Hermogenes Cayo), Jorge Preloran, 1970.

Jero Tapakan Series, Linda Connor, Patsy Asch and Timothy Asch, 1979–1983.

A Kalahari Family, John Marshall, 2001.

N!ai: The Story of a !Kung Woman, John Marshall and Adrienne Miesmer, 1980.

Neighbors: Conservation in a Changing Community, Richard Rogers, 1977 (digitally remastered 2014).

On the Spring Ice, Sarah Elder and Leonard Kamerling, 1975.

Pittsburgh Police Series, John Marshall, 1971–1973.

Poto Mitan: Haitian women, Pillars of the Global Economy, Renée Bergan and Mark Schuller, 2009.

Root Hog or Die, Rawn Fulton and Newbold Noyes, 1978 (digitally remastered 2014).

Stori Tumbuna: Ancestors’ Tales, Paul Wol ram, 2011.

Trance and Dance in Bali, Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson, 1952.

(un)veiled: Muslim Women Talk About Hijab, Ines Hofmann Kanna, 2007.

A Weave of Time: The Story of a Navajo Family, Susan Fanshel, 1986 (digitally remastered 2014).

Suggestions for Further Reading

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History website. “A Million Feet of Film/A Lifetime of Friendship: The John Marshall Ju/’hoan Bushman Film and Video Collection, 1950–2000.” http://anthropology.si.edu/johnmarshall/

For information about our complete catalog of films, visit the Documentary Educational Resources website at www.der.org.

~~~

Alice Apley is Executive Director of Documentary Educational Resources, Inc. (DER), where she is focused on re-visioning the organization for the 21st century. Alice oversees all day-to-day activities at DER, including curation, marketing and exhibition of works in DER’s catalog and ensuring ongoing access to the collection for broad audiences through new digital strategies. She also leads the organization’s filmmaker services program. She has worked as director, producer and advisor on numerous documentary film projects, including co-director of Remembering John Marshall. Prior to coming to DER, Alice conducted audience research, program evaluation and impact studies for media, museum and community engagement projects. She has served as a board member for the Society for Visual Anthropology (SVA) and as a juror and co-coordinator for the SVA’s Film Festival. She holds an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology and a Certificate in the Culture and Media Program from New York University.