A Visual Essay. Text and photos by Álvaro Minguito Palomares

A Visual Essay. Text and photos by Álvaro Minguito Palomares

Oradour-sur-Glane is a symbol of the misfortunes of the Nation.

It is important to preserve this memory, so that a similar tragedy never repeats itself.

—Charles de Gaulle speech in Oradour-sur-Glane, March 1945

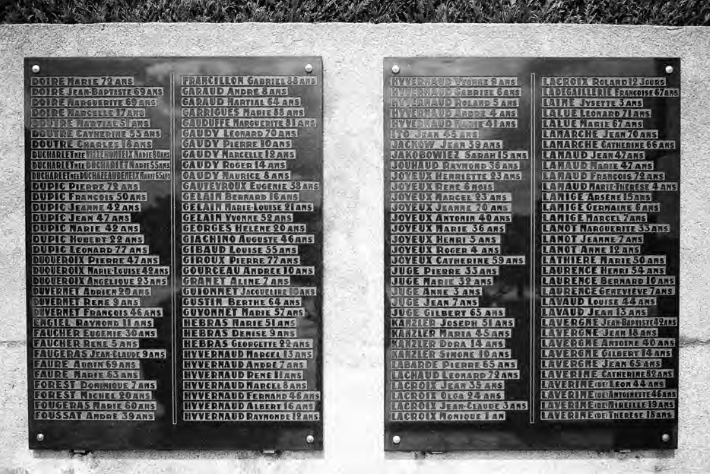

On June 10, 1944, only four days after Allied troops disembarked in Normandy, a German division of the Wafen-SS assassinated all the inhabitants of Oradour-sur-Glane, a village close to the French city of Limoges. Twenty-four of the victims were Spanish. Every year on the anniversary of the massacre, homage is paid to the 190 men, 245 women and 207 children who were shot or burned alive in the local church. After the massacre, Oradour-sur-Glane was completely destroyed by German troops. Under President Charles de Gaulle, the French government decided to leave the town in its state of ruin in order to convert it into a monument that would preserve memories of the barbaric events experienced there. In 1945, members of the exiled Spanish Republican government who were living in France inaugurated a memorial plaque that commemorated the tragedy. The plaque is the only tribute that any Spanish government has made to those who fell victim to the massacre. In 1946, the French government declared Oradour-sur-Glane a national monument.

My story intersects with that of Oradour-sur-Glane through a series of contrasts. I am concerned with the tension that exists between the forms of memorialization and acts of memory in a French village just 600 kilometers from my hometown of Madrid. I am also aware of the difficulty with which similar forms of remembrance are activated in my own country. In fact, my interest in Ora-dour-sur-Glane is a direct result of my experience documenting the movement to recuperate historical memory in Spain. In 2009, after numerous conversations with Luis Ríos, a biologist who works with the Basque forensic team at the Aranzadi Science Society in San Sebastián, I decided to initiate a long-term project that would chronicle the process through which teams of archaeologists, forensic specialists and volunteers exhumed mass graves that contained the remains of Republican supporters. With this project I sought to document the experiences of the individuals who initiate and participate in these endeavors, particularly the victims’ kin and the community members.

My story intersects with that of Oradour-sur-Glane through a series of contrasts. I am concerned with the tension that exists between the forms of memorialization and acts of memory in a French village just 600 kilometers from my hometown of Madrid. I am also aware of the difficulty with which similar forms of remembrance are activated in my own country. In fact, my interest in Ora-dour-sur-Glane is a direct result of my experience documenting the movement to recuperate historical memory in Spain. In 2009, after numerous conversations with Luis Ríos, a biologist who works with the Basque forensic team at the Aranzadi Science Society in San Sebastián, I decided to initiate a long-term project that would chronicle the process through which teams of archaeologists, forensic specialists and volunteers exhumed mass graves that contained the remains of Republican supporters. With this project I sought to document the experiences of the individuals who initiate and participate in these endeavors, particularly the victims’ kin and the community members.

During a family trip to France, someone told me about the horrible events that had occurred in Oradour-sur-Glane. The tragic parallels between the town’s history and the experiences of the thousands of people who experienced repression during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) made me pause. Although there are no “official” statistics regarding Francoist repression, experts estimate that anywhere between 120,000 and 160,000 individuals were brutally assassinated and thrown into mass graves located across the country. It is a story that was silenced during Francisco Franco’s long dictatorship (1939–1975) and further forgotten during the democratic transition, which heralded historical forgetting as a key in the struggle to modernize and move forward. To me, the story of Oradour-sur-Glane was in many ways the story of those who fell victim to Spanish fascism. However, the similarities between this microcosm of terror and that of Spain could not be extended through time. In France, homage would be paid to the victims. In Spain, Franco’s rule would make this impossible.

During a family trip to France, someone told me about the horrible events that had occurred in Oradour-sur-Glane. The tragic parallels between the town’s history and the experiences of the thousands of people who experienced repression during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) made me pause. Although there are no “official” statistics regarding Francoist repression, experts estimate that anywhere between 120,000 and 160,000 individuals were brutally assassinated and thrown into mass graves located across the country. It is a story that was silenced during Francisco Franco’s long dictatorship (1939–1975) and further forgotten during the democratic transition, which heralded historical forgetting as a key in the struggle to modernize and move forward. To me, the story of Oradour-sur-Glane was in many ways the story of those who fell victim to Spanish fascism. However, the similarities between this microcosm of terror and that of Spain could not be extended through time. In France, homage would be paid to the victims. In Spain, Franco’s rule would make this impossible.

When I arrived in Oradour-sur-Glane, I could see that a small road separated the old town from the new one. I entered the ruins through a small building where visitors were offered information regarding the terrible events that took place in the village. In addition to souvenirs and exhibitions, visitors were also presented with materials that contextualize the massacre in relation to World War II. Entry into the ruins was free of charge.

When I arrived in Oradour-sur-Glane, I could see that a small road separated the old town from the new one. I entered the ruins through a small building where visitors were offered information regarding the terrible events that took place in the village. In addition to souvenirs and exhibitions, visitors were also presented with materials that contextualize the massacre in relation to World War II. Entry into the ruins was free of charge.

After crossing through the tunnel that led to the town’s main avenue, I found myself again in daylight. A sign to the left of the road, resting against a tree, asked for “silence.” This silence was the only presence that appeared to inhabit the village. It was an eerie, overwhelming silence that the memorial’s visitors respected as they walked through a space marked by both horror and remembrance. To both my left and my right, I could see the ruins of schools, cafés, butcher shops, garages, bakeries and hotels, until I reached the main square where a dilapidated Citroen emerged as the landscape’s principle protagonist.

After crossing through the tunnel that led to the town’s main avenue, I found myself again in daylight. A sign to the left of the road, resting against a tree, asked for “silence.” This silence was the only presence that appeared to inhabit the village. It was an eerie, overwhelming silence that the memorial’s visitors respected as they walked through a space marked by both horror and remembrance. To both my left and my right, I could see the ruins of schools, cafés, butcher shops, garages, bakeries and hotels, until I reached the main square where a dilapidated Citroen emerged as the landscape’s principle protagonist.

History tells that the men living in Oradour-sur-Glane were gathered and shot at different locations throughout the village and that the women and children were brought to the church located at the end of the main road. The story goes that these women and children were burned alive in the church. Little remains from the original building. The few structures that survived the fire are the confessionals, where it is rumored that several terrified women tried to hide their infant children. At present, there are revisionist historians who try to negate these events. They accuse the townspeople of having collaborated with anti-fascist resistance, and they suggest that the village’s inhabitants burned the church. They deny that the tragedy was an act of violence.

History tells that the men living in Oradour-sur-Glane were gathered and shot at different locations throughout the village and that the women and children were brought to the church located at the end of the main road. The story goes that these women and children were burned alive in the church. Little remains from the original building. The few structures that survived the fire are the confessionals, where it is rumored that several terrified women tried to hide their infant children. At present, there are revisionist historians who try to negate these events. They accuse the townspeople of having collaborated with anti-fascist resistance, and they suggest that the village’s inhabitants burned the church. They deny that the tragedy was an act of violence.

In Spain, time runs in favor of those who ignore those responsible for the massacre in Oradour-sur-Glane and the many big and small acts of violence experienced during the Spanish Civil War and its aftermath. Unlike France, whose government has sought to preserve this small village as material evidence of a historical event that should never be repeated, my country, Spain, struggles to engage in similar acts of remembrance. Those who most defiantly resist memory are protected by courts of law and sheltered by political power. They are free to deny the rights of the hundreds of thousands of individuals lost to the Spanish Civil War and its aftermath. They are free to deny these victims’ rights to be remembered. Thirty-six years of a cruel dictatorship and 39 years of the so-called “Spanish Transition” have tried, once again, to bury our past. Our most important and pressing struggle today is the battle against historical forgetting.

An earlier version of this essay is available on the Novecento Collective’s blog (http://colectivo novecento.org).

Translation from the original Spanish by Anthropology Now Visual Essay Editor Lee Douglas.

Álvaro Minguito Palomares is an economist and a documentary photographer. He is also one of the photo coordinators for the Madrid-based newspaper Diagonal. His photographic work has been showcased in numerous publications, including Eldiario.es, Gara, Directa, Madrid 15m, VientoSur, Adbusters and narrative.ly. Throughout his professional career, Minguito has sought to document social expressions of solidarity by acting as a witness to a wide range of political, social and urban movements. Passionately dedicated to stories hidden at the margins of everyday life and mainstream media, he embraces photography as a medium that can narrate and make visible stories regarding inequality and injustice, as well as victory and joy.

Combining political activism with photographic documentation, Minguito has participated in a number of Madrid-based collectives, including Quieres Callarte and the Colectivo Novecento. He has been an active participant in a number of Madrid-based social movements and was a founding member of the DISOPress Agency that was borne out of the “15M” movement that took over the city of Madrid in May 2011. Bring- ing together writers and image-makers committed to independent journalism, DISOPress is at the forefront of new Spanish documentary work that seeks to call attention to the effects of Spain’s current economic and political crisis. Minguito is currently an anthropology student at the Universidad Nacional de Educación a la Distancia in Madrid, Spain. His work can be seen at http://www.alvarominguito.net and http://disopress.com.