On February 25, 2014, at eight in the morning, the sky had barely turned light. In a muddy excavation site five stories below street level, an equipment operator deftly maneuvered his skid-steer, bathed in powerful electric lights. After two years of digging through sand and mud, the excavation phase of the Transbay Project was only days from completion. With rain predicted, the crew was anxious to wrap up when the operator saw something in the mud — which turned out to be a human bone.

It was sheer luck the operator was able to see the bone. A skid-steer is a small piece of earthmoving equipment commonly referred to as a “Bobcat,” after a popular brand. It is often used for small residential projects such as preparing lawns and planting bushes. Most of the excavation for the Transbay Project had been done by massive excavators weighing about 100 tons, which could easily pick up a skid-steer in their huge buckets. With no monitor available, the most skilled, sharp- eyed operator would be hard-pressed to spot a human bone from the excavator’s cab. But for this last bit of earthmoving work, the skid-steer was just the right tool.

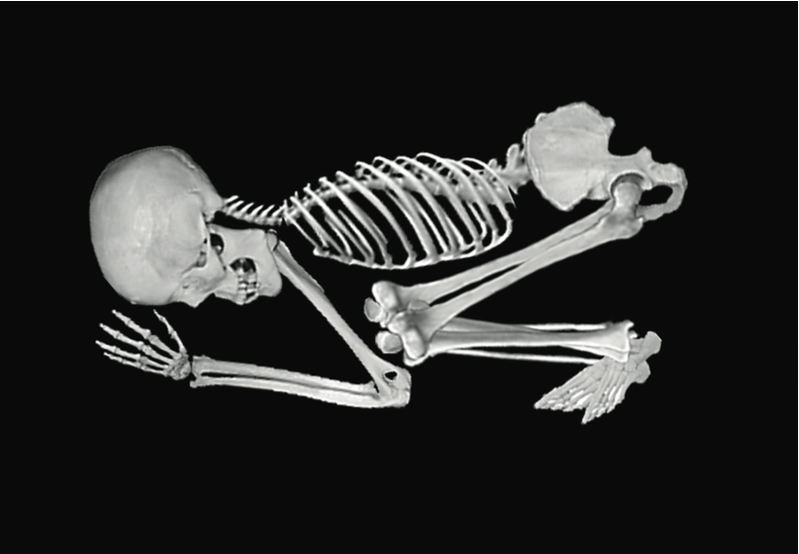

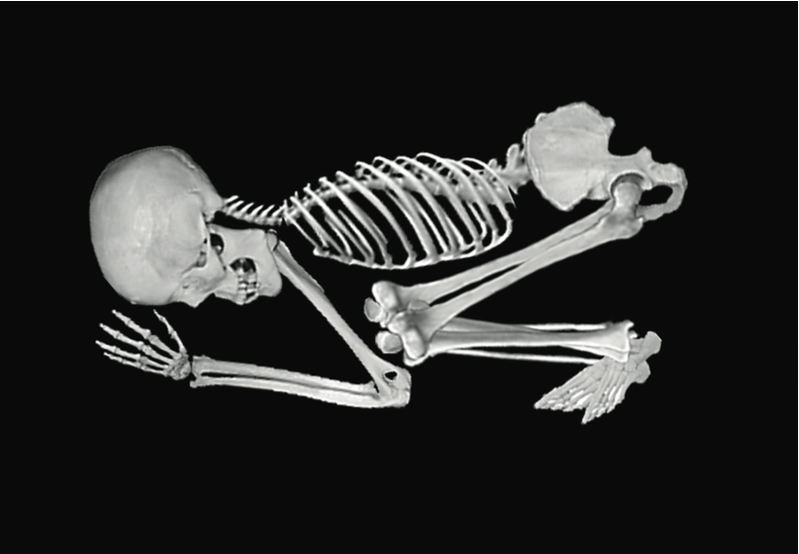

The operator had found the grave of a young man who lived long ago in what is now downtown San Francisco. The body had been folded into the fetal position, wrapped in woven matting and buried with wooden tools. The location, now separated from the Bay by a quarter mile of skyscrapers perched on reclaimed land, was at that time close to the water’s edge. Perhaps the man’s family chose to bury him in his favorite place for hunting duck eggs, collecting oysters or just sitting and gazing out over the waves as the setting sun lingered on the East Bay hills. In any case, the choice was fortuitous because the young man was buried in dense, marshy soil that squeezed out nearly all the oxygen bacteria need to live. As a result, the remains were startlingly well preserved, down to the basketlike shroud.

Carbon-14 analysis of organic matter found near the burial indicated that this young man lived about 7,500 years ago. That makes “Transbay Man” one of the oldest human remains ever discovered in California. And the condition of the remains and associated artifacts makes them prime candidates for DNA testing and other scientific analysis.

However, nothing of the sort has occurred. After a short article in the San Francisco Chronicle announced the discovery, nothing more was reported. Months later, the newspaper ran an editorial headlined “Con- struction crew’s discovery of human remains can’t stay buried.” Nonetheless, that is exactly what has happened.

I first became interested in these matters when I managed Los Vaqueros, a water supply reservoir tucked into a deep canyon at the sun-blasted eastern edge of the Bay Area. When expansion of the reservoir in 2011 threatened to expose a Native American burial site, I worked with consulting archaeologists to strike the balance between informing the public and respecting the sanctity of the site. Learning about the Transbay discovery from a colleague in late 2014, I quickly became determined to unravel the mystery.

The Transbay Joint Powers Authority, a partnership of several government agencies including the City of San Francisco, is responsible for the $4.5-billion project on the site of the old Transbay Bus Terminal. The Authority’s 21st floor offices — overlooking the job site — contain an archaeology exhibit featuring an array of Gold Rush–era glass bottles and ceramic dishes found during the Transbay construction, along with a plaque reflecting a state award for the project’s historic preservation measures. But there is no mention of Native Americans, not even on the panel entitled “The Movement of Cultures.” The receptionist acknowledged to me that Native American remains were found, but “we don’t talk much about them, out of respect for the dead.” The reality is a bit more complicated than that.

James Allan is vice president of the archaeological consulting firm William Self Associates and serves as the project archaeologist for the Transbay Authority. I spoke to him in his firm’s rabbit warren of offices crammed with files and decorated with photos of prized artifacts. In his decades of consulting, Allan has worked with hundreds of Native American burials, but this one was unique for its combination of age and condition. Allan outlined for me some of the insights that might be gained from study of the discovery and identified the scientists who had agreed to undertake analysis of the remains.

One of those was Jelmer Eerkens, an anthropologist at the University of California at Davis who specializes in stable isotope analysis. On a rainy day in early 2015, I drove up to meet him. Eerkens’ lab is located in a putty-colored institutional building with rusting outdoor stairs that were littered with puddles on the blustery day I visited. Located at the far end of a poorly lit hall, the lab features tables piled with dusty oyster shells rather than shiny high-tech equipment — the chemical analysis is conducted elsewhere on the sprawling campus. But the professor’s warmth and enthusiasm for his topic lit up the room. He was excited about the prospect of analyzing the Transbay bones, he explained, simply because of the importance of such an ancient find.

By precisely measuring the ratios of heavier to lighter isotopes in bones, Eerkens can identify the location of the water an individual drank and suggest where she spent her life. Similar analysis of stable isotopes of nitrogen, strontium and carbon can shed light on whether an individual ate mostly plants or animals, her dependence on ocean-based sources of food, and other features of her everyday life.

When the remains of Richard III were unearthed in a parking lot in Leicester, England, in 2012, stable isotope analysis was conducted on the bones and teeth. Study of the isotopes attributable to water indicated that Richard was born in eastern England but later moved to the west as the fingerprint left by the water in his teeth and bones changed over time. Other isotope analysis suggested that his diet changed markedly when he became king, including quantities of wine and exotic delicacies such as peacock and swan. The findings matched what the historical records tell of Richard’s life. Analysis of the Transbay remains could yield equally fascinating insights into what the man ate and where he traveled in his short life.

Allan, the project archaeologist, also lined up researchers at the University of California, Santa Cruz, to conduct DNA analysis on the Transbay remains. Their analysis would compare the genetic makeup of this man who lived 7,500 years ago with other ancient skeletal remains from the West Coast, as well as with current native populations in California and Asia, from where the first Californians are thought to have migrated. But under California law there needs to be agreement between the archaeologists and the living descendants before any scientific analysis can be done. This is often difficult to reach.

On the day of the discovery, the county coroner was called in to verify that this was an ancient burial and not a crime scene. As required by California’s Native American Historical, Cultural, and Sacred Sites Act, the next call was to the California Native American Heritage Commission (NAHC), a small agency headed by seven Native Americans appointed by the governor. Whenever Native American remains are unearthed in the course of a development project, NAHC is charged with identifying the “most likely descendant” (MLD) of the person whose remains were discovered. The MLD becomes, in essence, the representative of the deceased.

When a Native American burial site is found within the territory of a tribe that has been recognized as a governmental authority, NAHC designates the tribe as MLD. The tribal government typically has a cultural sites protection committee, which oversees the tribe’s work on the project and expresses the desires of the tribe. However, where discoveries occur in areas not attributed to a recognized tribe, the designated MLD may simply be an individual whose ancestors lived in the area.

For the Transbay discovery, NAHC selected as MLD Andrew Galvan, a Native American who signs his emails “An Ohlone/Bay Miwok Man.” That identifier hints at the complexity of the San Francisco Bay Area’s Native American community. The Coast Miwok people are generally associated with the redwood forests of Marin and Sonoma counties, north of San Francisco. For this reason, the tribe received vicarious, though obscure, fame by inspiring George Lucas to call his redwood-dwelling Star Wars creatures “Ewoks.” But Miwoks also lived in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, and some early maps show their territory wrapping entirely around San Francisco Bay. Certain bands of Miwok have been granted formal recognition by the California or federal government, but none of those are close to San Francisco itself.

The Ohlone label is more often applied to Native Americans in San Francisco and the East Bay. However, many Native Americans (and others) have pointed out that there is no Ohlone tribe; the term is generally applied as a catchall for several distinct territorial groups with related cultures and languages in the Monterey/San Francisco region. No group of Ohlone is recognized by the federal government. However, two groups are recognized by the State of California — the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band centered on Monterey Bay, and the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe in the San Francisco Bay Area. The Muwekma Ohlone, chaired by Rosemary Cambra, claim to represent all the Ohlone descendants in the Bay Area. However, a number of locals with Ohlone ancestry (most of whom are related to Cambra) beg to differ.

Ramona Garibay, universally known as Mona, and her mother, Ruth Orta, are two of those. I met them in Union City, a working-class East Bay suburb, at Garibay’s immaculate yellow clapboard house, fronted by a cozy porch and a freshly painted white picket fence. Garibay serves as a monitor at construction sites and was retained by the project archaeologist for the Transbay Project. But because the discovery occurred in a “low risk” location, she was not on site at the time and, sadly, never saw the remains.

Garibay and Orta by no means consider themselves to be Muwekma Ohlone, which they refer to as “Rosemary’s group” — they suspect that Cambra “made the name ‘Muwekma’ up herself.” According to Garibay, their feelings toward Cambra are shared by their entire family, which by Orta’s count encompasses her seven children, 17 grandchildren, 35 great-grandchildren and “two great-greats.” By all accounts, Galvan, who is related to both Garibay and Cambra, is another who does not consider himself one of the Muwekma Ohlone — though he is not especially close to Garibay or Orta, either.

Since the Muwekma Ohlone tribe is recognized by the statue of California and counts San Francisco as being within its ancestral lands, the NAHC might have decided to select the tribe as MLD for all discoveries in the city. However, perhaps to avoid taking sides in the internecine conflict, the Commission chose a different solution. It requested local Native Americans to submit documentation showing their connection to specific geographic areas in the Bay Area. As it happens, NAHC approved four MLDs for San Francisco — Cambra, Garibay, Galvan and a woman named Katherine Perez. Those four individuals are selected on a rotating basis. For the Transbay discovery, Galvan’s name was up.

The law empowers the MLD to make “recommendations or preferences for treatment” of the remains, as well as for any items “associated” with the remains, but does not require the landowner to accept the MLD’s recommendations. However, if the parties are unable to reach agreement, the statute directs the landowner to rebury the remains and associated items on the property in a location where they will not be disturbed again. Given the differing perspectives of landowners, archaeologists and Native Americans, the statute invites conflict, and all too often that is the outcome. In this case, it seems clear that Galvan, as MLD, and the officials of the Transbay Authority reached an impasse. The interesting question is why.

Often, tensions arise when archaeologists wish to transport remains to their labs for close examination while the Native Americans prefer to keep custody of the remains and minimize the handling of the bones until they can be reburied in a secure spot. When DNA or stable isotope analysis requires bits of bones or teeth to be removed, it may increase the descendants’ concerns.

Often, tensions arise when archaeologists wish to transport remains to their labs for close examination while the Native Americans prefer to keep custody of the remains and minimize the handling of the bones until they can be reburied in a secure spot. When DNA or stable isotope analysis requires bits of bones or teeth to be removed, it may increase the descendants’ concerns.

A deep-seated resistance to disturbing the dead has been noted repeatedly among Native Americans across otherwise diverse tribes and regions. In 1996, the Society for American Archaeology devoted a large part of its annual meeting to an effort to mend the often-troubled relations between Native Americans and archaeologists. In a book of essays stemming from those sessions, respect for the dead was a recurring theme from the Native Americans who participated:

In our way of life when a person dies, there is a certain funeral address which tells us what to do. We leave them alone, they are through. They have given what information they want. They have done their jobs; we need not bother them anymore. That is why they go to their rest; they have finished their job here, and it is very important to us that we do not disturb them anymore. [1]

These sentiments were echoed by many of the Native Americans I met, including Chuck Striplen, a Native American ecologist with a neat ponytail and a quick laugh. I spoke with Striplen at his office at the San Francisco Estuary Institute, which undertakes research to improve the management of the Bay. As both a Native American and a scientist, Striplen has an interesting perspective. He shared his personal view that any Native American remains unearthed in a development project should be reburied as quickly and as close to their original burial site as possible. “This is what our elders taught us,” he said.

Striplen told me he sees little justification for much of the invasive testing often carried out on Native American remains. He pointed out that there are many other sources for information on how his ancestors lived, such as the middens he has been analyzing (ancient mounds containing animal bones, oyster shells and other detritus left behind). As he sees it, many of his colleagues are all too eager to destroy human bones in the name of science.

Archaeologists have tended to view the “archaeological record,” the human remains and tangible artifacts of a civilization, as the primary, if not the only, source of knowledge, while Native Americans have shaped and maintained their history through oral traditions handed down from generation to generation. In recent years, however, archaeologists’ attitudes have evolved. Roger Anyon, an archaeologist who participated in the 1996 conference, noted that “oral traditions and archaeology represent two separate but overlapping ways of knowing the past. There is no doubt that a real history is embedded in Native American oral traditions, and that this is the same history archaeologists study” [2] The two modes of thinking about the past seem to be converging, with archaeologists looking to oral traditions to inform their theories and Native Americans becoming more interested in learning about the archaeological record.

Native Americans’ concern for the sanctity of the dead is hardly unique. Cemeteries are universally accorded special treatment — state laws across America protect them from being disturbed. Cate Ludlam campaigned for years for preservation of a pre–Revolutionary War cemetery in Queens, New York, in which Civil War-era ancestors of hers are buried. In an interview with New York’s DNAInfo, she explained her motivation with words that echo the sentiments of the Native American speaker at the 1996 archaeological conference: “The way I was raised, you respect the last resting place of the dead” [3].

The handling of Richard III’s remains is also instructive. When the remains were discovered, the University of Leicester first consulted with Buckingham Palace to make sure there was no objection to analysis and then gained the approval of the university’s ethics committee before authorizing extensive DNA testing. Even so, when the university announced plans to rebury the king in Leicester, a group of Richard’s relations filed suit, claiming they should have a say in how the remains are treated. The Ministry of Justice ultimately denied their claim.

Indeed, burial ceremonies and other rituals surrounding death are common to every human culture; they can be considered one of the fundamental attributes of humanity. Native Americans sometimes rail at the concept that their concerns are unique. Defending his tribe’s refusal to allow study of their ancestors’ remains, a Bay Area tribal chair asked the San Francisco Chronicle: “How would Jewish or Christian people feel if we wanted to dig up skeletal remains in a cemetery and study them?” [4]. As the Richard III controversy shows, people tend to bridle when outside authorities assert control over their ancestors’ remains.

Nor are Native Americans uniform in their opinions. MLD Ramona Garibay supports archaeologists’ efforts to learn more about the lives and culture of her forebears using all available resources, including invasive techniques. Jelmer Eerkens, the University of California professor, recently published an article exploring the childhood diets of Native Americans living near Los Vaqueros Reservoir [5]. It was based on stable isotope analysis completed with Garibay’s approval. And Cara Monroe, a Washington State Uni- versity anthropologist, published a study of the impacts of famine on ancient Native American tribes [6]. The study used DNA material provided by the Muwekma Ohlone Tribal Council.

***

As I delved into these broader issues, I struggled to learn more about the young San Franciscan buried in the marsh. I contacted the Joint Powers Authority to interview the individuals who made the Transbay discovery. The official I reached was cordial but failed to respond to my requests. I reached out to several staff members in the San Francisco City government who worked on the project. Eventually, I received a call back from a public affairs officer. We discussed my request and she promised to get back to me, but never did. The same pattern was repeated with NAHC. I went back to James Allan, the archaeologist who was my first source. He regretfully informed me that there was nothing more he could share; the entire incident is considered confidential.

For some reason, the agencies did not want the ancient San Franciscan’s story to be examined, which only increased my determination to bring out the facts. So I contacted the single person with the most knowledge: Andrew Galvan. Everyone I had spoken to who knew Galvan (and most did) agreed that he would be more than happy to grant an interview, and in his first email response he offered to meet with me some weeks in the future. I waited and followed up by email, but the date passed. As time went on, Galvan’s responses lagged and then ceased entirely. I was getting nowhere.

My last option was to submit document requests to the government agencies under California’s Public Records Act, the state equivalent of the federal Freedom of Information Act. In response, the agencies cautioned that many documents would be withheld or redacted “out of respect for the Native American community and to ensure the remains are treated with appropriate dignity.” I received a deluge of digital records pocked with deletions.

Apparently, the statute’s limits on disclosure mean different things to different agencies. The City of San Francisco carefully redacted Galvan’s name each time it appeared in the documents the City produced. The Joint Powers Authority (of which the city is a major partner) left Galvan’s name visible throughout its voluminous production. On the other hand, the Joint Powers Authority completely blanked out the text of a draft press release about the discovery, while the city included the release with only a few lines redacted.

In the end, I was able to reconstruct most of the story from the documents. NAHC designated Galvan as the MLD within a day after the discovery. Over the next two weeks, Galvan and the project staff agreed on recommendations for management and treatment of the remains. The project authority also signed a “consulting services agreement” to pay Galvan up to $20,000 for his services. The description of those services is completely redacted, but they would typically include monitoring the excavation, taking custody of the remains and cleaning or other care of the remains. With the agreement in place, the painstaking excavation of the remains could go forward, and the construction could be completed.

Galvan’s recommendations for treatment of the remains shed light on his attitudes about the sanctity of ancestral burials. His “Guidelines for Respectful and Dignified Treatment of Human Remains,” prepared for the construction crew, outline detailed rules of conduct. Radios, tobacco and meals are prohibited, and cell phone conversations must be conducted “at a respectful distance” from the remains. The limits extend equally to Native American practices: no drumming, burning of “sweet-grass” or other rituals are to be allowed, except by the MLD himself. The guidelines also specify that the remains and associated grave goods would be buried at Galvan’s Ohlone Indian Cemetery in Fremont within one year of discovery.

Other communications make clear that Galvan did not oppose scientific analysis of the remains. Minutes of meetings in early April 2014 indicate that testing was to include DNA analysis, radiocarbon dating and isotope analysis. The documents indicate the MLD and the project authority hoped to answer the questions described to me by Professor Eerkens. However, money quickly surfaced as an obstacle.

In early May, Galvan noted that only $5,700 remained from his original $20,000 contract. Throughout the summer, project staff searched for funding for the lab work. Their efforts were not in vain; academics from the University of California agreed to cover the cost of analyzing the stable isotopes and DNA in the bones. In August, the genetics firm 23andme agreed to undertake DNA analysis of local Native Americans for comparison to the ancient DNA, at no cost to the project.

By September, the funding gap was reduced to one last issue: paying the MLD to monitor the scientists while they did the analytical work. While heavily redacted, the documents produced reflect dozens of emails, meetings and memos as the project staff and the MLD haggled about the ongoing costs, the scope of the MLD’s future work and the language of a press release. An email from early September expressed despair that funding would be found and stressed the need for all the agencies to be aware of “the potential for reburial prior to the completion of scientific analysis.”

Finally, in mid-September, City staff obtained funds from the federal Department of Transportation. A new contract with Galvan was drawn up, dated October 1. Attached to the contract is the draft press release, which proclaims the significance of the discovery:

Scientists said the remains, which were discovered at the site of the new Transbay Transit Center in February 2014, are approximately 7,570 years old, dating back to 5620 B.C. They are among the oldest ever recovered in Central California, and are 2,500 years older than Ötzi, Europe’s famous mummified “Ice Man” recovered in 1991. … Most Likely Descendant Andrew Galvan, who is responsible for providing guidance and recommendations regarding the sensitive recovery, treatment, and re-burial of the remains, will be an important part of the testing process, ensuring that every step of the remains’ transport and study is conducted appropriately.

But the contract was never signed; the press release was never issued; and the analysis was never completed. An email from Galvan to the Transbay Center’s Construction Manager states that “many, many, many changes” are required; the much-negotiated press release is “most alarming”; and the requirement that Galvan get approval from the authority to talk with the media “won’t work.”

Just about then, the parties seem to have stopped talking. A final, heavily redacted email from the project staff reflects their frustration. The project authority “does not have the staff resources or the financial means to manage the MLD. We have attempted to negotiate an agreement with the MLD using our available resources. However, he has not accepted our offer. … He is now refusing to sign the agreement we provided, so [the authority] has run out of options to continue.”

Just about then, the parties seem to have stopped talking. A final, heavily redacted email from the project staff reflects their frustration. The project authority “does not have the staff resources or the financial means to manage the MLD. We have attempted to negotiate an agreement with the MLD using our available resources. However, he has not accepted our offer. … He is now refusing to sign the agreement we provided, so [the authority] has run out of options to continue.”

And with that, the trail ends. There appear to have been no more negotiations, no more emails and no more meetings.

What will become of the remains of the young San Franciscan is unclear. None of the documents produced by the agencies provide information on this. Perhaps they are being stored by Galvan — his guidelines for the construction crew specify that the remains will be removed by the MLD. Perhaps they have already been buried in the Fremont Ohlone Cemetery, as Galvan intended. Perhaps the remains lie beneath the massive rising towers of the new Transbay Center. For now, it is a mystery whether the young man’s remains will be studied, be reburied or just languish in a jurisdictional limbo.

Acknowledgements

I thank Heather Price for starting me on this road and providing support throughout, and Chuck Striplen, whose thoughtful input was invaluable to the project.

Notes

1. G. Peter Jemison, “Who Owns the Past?” in Native Americans and Archaeologists: Stepping Stones to Common Ground, ed. Nina Swidler et al. (Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press, 1997) (quoting Geraldine Green of the Seneca tribe), 66.

2. Roger Anyon et al., “Tradition and Archaeology” in Native Americans and Archaeologists: Stepping Stones to Common Ground, ed. Nina Swidler et al. (Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press, 1997), 85.

3. “Colonial Cemetery Set for Rejuvenation in Queens” DNAinfo | New York, February 10, 2012 (DNAinfo.com, accessed January 6, 2016).

4. Peter Fimrite, “Indian Artifact Treasure Trove Paved Over for Marin County Homes,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), April 23, 2104. (Web, accessed January 6, 2016).

5. Jelmer W. Eerkens and Elmer J. Bartelink, “Sex-Based Weaning and Early Childhood Diet Among Middle Holocene Hunter-Gatherers in Central California,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology. Published online October 11, 2013, Wiley Online Library.

6. Rick W. A. Smith, Cara Monroe, and Deborah A. Bolnick, “Detection of Cytosine Methylation in Ancient DNA from Five Native American Populations Using Bisulfite Sequencing,” PLoS ONE 10(5): e0125344. doi:10.1371/journal.pone. 0125344.

Peter W. Colby practiced environmental and real estate law for many years. For the past 15 years he has worked on land acquisition for conservation purposes, including a number of transactions with Native American tribes. He also writes and teaches at the college level in the San Francisco Bay Area.

6 Responses

I am in fact the person who solely uncovered the remains at the translation site! I was the superintendent on the project at the time and I have a story, the true story to tell and that needs to be heard and reported! I have waited a long time for this opportunity and you are my source! Thank you for your article and I am very anxious to discuss this with you! My life has been greatly affected by my discovery of the remains, and I assure you, not in the ways one would assume! James k. Walker

I would like to hear your story! Right now, we in West Berkeley are awaiting a CEQA study of the West Berkeley shellmound that’s being considered for a huge shopping center, 160 apartments and a 6 story parking garage. This is in the landmarked lot where the West Berkeley shellmound stood, and during construction on the warehouse store right across the RR tracks, 95 separate burials were discovered, many had to be left to avoid undermining the tracks. In the past few months directly East of the site, three separate sets of human remains have been found while installing new stormdrains, and testing by Caltrans when fixing up the railroad found 17 separate sites of undisturbed cultural remains, some only 18 inches from the surface, in the roadway all around the site.

Despite the overwhelming evidence of the shellmound and the presence of bodies on all sides of this lot; Andy Galvan, who is being paid by the developer, has declared that there is absolutely no chance that any part of the shellmound lies under the pavement, and the developer is taking his declaration to the bank.

The developer has now offered a $75,000 scholarship for the Ohlone, or a native language course, but Andy decided that a better “mitigation” for destruction of the shellmound would be for him to take that money for his Mission San Jose work. The destruction of an ancient sacred burial site can’t be mitigated by throwing money at a distant Catholic Mission, which in itself holds bitter memories for those who trace their ancestry in this area back millennia. As you can guess, there is quite an uproar in this City, but Berkeley is no longer progressive and they haven’t passed on a luxury highrise in the past 10 years. I have a feeling that the buy-off price will climb to $125,000 before Berkeley signs off on this “mitigation” and Andy will take the money for his own project. (except for the $125k, the rest is in the public record on the City’s website)

I feel in the tone of your letter that you had a powerful experience in discovering this burial, and I would love to hear it. We need to have personal individual stories to present to the Zoning Board when this project comes before them. Let me know if you’d like to share.

rhiannon

James K. Walker, I have been involved studying the shellmounds since 2000 and would like to hear or read your story about the find at the Transbay Terminal construction site. Where can I read your story?

Wonderful work. I discovered the possible location of another shellmound in SF a few years ago. I believe the city has locked the records of that site down. Doing a bit of work with a local Ohlone activist, I found out that there is a special registry in Santa Rosa for burial sites. This issue is of course very sensitive as you mention, and access to the registry is restricted to a very few people only, for good reason as a mechanism to protect locations from further tampering. Imagine, if there was true respect for these locations by this culture, the ones still intact could be repaired, and buildings or other structures removed and the locations be given due respect as are western graveyards.

To understand why Galvas ended his agreement, you have to go back to 2007 when another investigation of him was done by the SF Weekly. It was his fear of his name being used publicly in the press release that caused him to back out. He was afraid that the story would bring back the SF Weekly history!

http://archives.sfweekly.com/sanfrancisco/bones-of-discontent-andrew-galvan-carves-a-unique-controversial-role-in-relocating-native-american-skeletons/Content?oid=2165208

That extended piece details his non-profit burial business operations that he runs as well as being a curator over at Mission Dolores.

I would suggest, that the controversy that you dug into, but did not go into has to do with how tribal ancestors relate to Euro culture, and more specifically what happened to them and their families individually.

The neophytes, or those who were victims of Spain’s colonization here that included forced Christianizing upon them at gunpoint as part of Mission history as just the first step in what was to follow. The coastal tribes (Ohlone) were gathered like acorns against their will and forced into slavery. Those that resisted the spiritual brainwashing did not live, unless they escaped or were lucky enough to flee from their homes before being dragged into the Missions.

In 1927, as part of the federal process where tribes obtained formal acknowledgement, that registration process included massive cultural brainwashing by U.S. American churches that removed their cultural and religious values of children as specially organized schools, with those who fought it, especially with women being treated by eugenics styles sterilization and more.

Today, there are those who fully identify with this culture, like Galvan, but like good Americans wish to capitalize on his ancestors. This group of ancestral people have no problems living in this culture. In reservations, there is another group very similar that actively seeks to repress their fellow tribal people. And then there are those that wish to bring back their traditional values. Doing this in the Bay Area is not easy, due to the economic straight jacket placed on all by the system.

Note that the catch 22 federal process has intentionally made it nearly impossible for Ohlone communities to obtain federal status, because the primary requirement to gain status is to have land, which was intentionally excluded by the Mexican government, that looked the other way immediately following the 1833 act, as Spanish Californios never told the Ohlone that they could get land and stay, but were instead driven into the Sierras.

For non-registered tribes that were intentionally ignored like the Ohlone, many of whom hid their real identities to protect themselves from the genocide of militias that were paid to hunt down and kill tribal people across California as part of the 1850 Indian Protection Act and the state’s first bond to pay for the genocide that followed after statehood. So the attempt by First Nation ancestors to hold onto their traditional values was almost impossible to do like Galvan’s family who were forced to acculturate.

Galvan and his ancestors are classic victims of Spain and the Catholic Church’s papal bulls that allowed Europeans to this day via the Doctrine of Discovery to take their lands, convert them to Christianity or enslave them in perpetuity if they refuse to convert.

Is there any new information to follow up with?

“Watching the sun set in the East Bay hills.”

Maybe reflected off the East Bay hills.