In The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, a novel by the Spokane author Sherman Alexie, a basketball player at an all-White high school is the persistent target of racist slurs. “Chief” and “Tonto,” he is called, “Squaw boy” and “Redskin.” He also experiences the indignity of sharing the court with a caricature of himself, the school’s pseudo-Indian mascot. The hilarious and hard-hitting novel, which won the American Book Award for young adult fiction, is based in part on Alexie’s own experience as captain of his high school basketball team, the Indians.

In lectures and media appearances such as his 2013 commentary at the University of Texas, Austin, Alexie drops the humor, calling pseudo-Indian mascots a “celebration of a history of genocide.” As he told Bill Moyers on a segment of Moyers & Company, “At least half the country thinks the mascot issue is insignificant. But I think it’s indicative of the ways in which Indians have no cultural power” (1). Many scholars and activists share this view. While unpopular with the owners and fans of various teams of “Chiefs,” “Braves,” “Indians” and “Redskins,” this critical perspective on mascots is the only one that addresses some puzzling questions: Why is it that long after Little Black Sambo and the Frito Bandito have been banished to the history books, sports teams continue to promote themselves with names, symbols, practices and paraphernalia that demean and degrade Native Americans? Why are professional teams stubbornly maintaining their pseudo-Indian trademarks even while schools and colleges, responding to decades of activism, retire their mascots? Why is this nowhere more visible than in our nation’s capital? And why do passions about this issue run so high?

This practice is as American as apple pie—or as American as a mid-20th-century children’s ABC book that illustrates the letter R with “redskin” (2) But unlike apple pie, pseudo-Indian sports mascots have dis- tinctly unhealthy consequences. They con- sign American Indians to a stereotypical social position that I think of as the “mascot slot.” Like the “savage slot” analyzed by anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot, the mascot slot is a way of objectifying, appropriating and signaling the inferiority of Na- tive American cultures and peoples. The mascot slot is certainly not, despite enthusiasts’ claims to the contrary, a way of honoring them.

Honor among Sports Teams

Social groups around the world have frequently marked their distinctiveness by associating themselves with plants, animals or natural features. In practices known as totemism (from an Ojibwa Indian word), groups mark their identity and observe various taboos associated with their totem, whom they believe to be a spiritual ancestor. Viewing pseudo-Indian sports mascots as a form of totemism highlights two of the most egregious aspects of such mimicry: first, sports mascots treat American Indians as if they are a part of nature rather than a part of culture. Second, sports mascots masquerade as a form of honor, respect and identification, while they are actually a form of racial disparagement and hierarchy.

Viewing American Indians as natural rather than cultural beings has long been a part of the Anglo-American national imaginary. Calling them “godless heathen,” “treacherous savages” and “wild redskins,” colonists and frontiersmen construed Native Americans as part of a wilderness that needed to be subdued and tamed. Sometimes Anglo-Americans (most famously, the 19th-century novelist James Fenimore Cooper) praised the “wilderness virtues” of Native Americans, such as their hunting and tracking skills. But “savage” and “redskin” also connoted such ignoble characteristics as filthiness, violence and unrestrained passion. Like traditional Hollywood Westerns, pseudo-Indian sports mascots continue this practice of pitting Indian “savagery” against Anglo-American “civilization.” Fans of teams called Indians, Braves and Redskins mimic what they take to be Native American cultural attributes—feathers, face paint, war whoops, tomahawk chops—in order to identify themselves and their team with what they see as a culture of fierce warriors.

Team owners and fans alike claim that this behavior respects and honors American Indians. But respect would mean giving Native American objections to pseudo-Indian imagery their due. As anthropologist Brenda Farnell and sports researcher Ellen Staurowsky have demonstrated, far from being forms of respect, pseudo-Indian trademarks, logos and mascots are actually forms of White privilege that demean and degrade Native American cultures. Using the same slurs and images that historically justified genocide and the seizure of land from Native peoples, teams of “Indians” attempt to wrest points or yardage from an opposing team. It is a ritual of cultural appropriation and entitlement, a grown-up form of “playing Indian,” in which Anglo-Americans replay their victory over Native Americans by imitating “chiefs,” “braves” and “squaws.” Adding insult to injury, proponents defend pseudo-Indian symbolism as forms of honor and respect, even in the face of prolonged claims to the contrary by those who feel demeaned and disparaged.

Not all uses of pseudo-Indian imagery are equivalent. The Haskell Indians represent Haskell Indian Nations University. The Florida State Seminoles have received official permission to use a tribal name and mascot, as anthropologist Jessica Cattelino has discussed. Some team logos—for example, Chief Wahoo of the Cleveland Indians—are patently more racist than others.

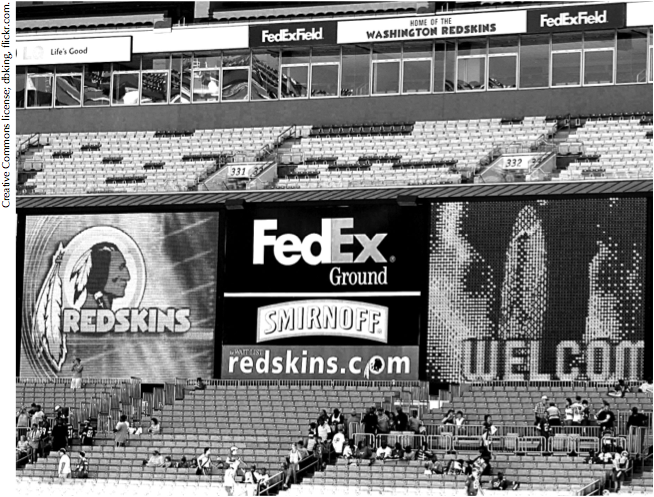

Some fan actions—say, the tomahawk chop of the Atlanta Braves—are more egregious. And some team monikers—most prominently, the Washington Redskins—are most blatantly offensive. This last example is currently the most contested.

redskin, n.

1. An American Indian. Now somewhat dated and freq. considered offensive.

c1769 tr. Mosquito in Papers Sir W. Johnson (1931) VII. 137, I shall be pleased to have you come to speak to me yourself if you pity our women and our children; and, if any redskins [Fr. quelques peaux Rouges] do you harm, I shall be able to look out for you even at the peril of my life.

1812 FRENCH CROW in J. C. A. Stagg et al. Papers J. Madison Presidential Ser. (2004) V. 182, I am a red-skin, but what I say is the truth.

1815 BLACK THUNDER in Niles’ Weekly Reg. 14 Oct. 113, I turn to all, red skins and white skins, and challenge an accusation against me.

1823 J. F. COOPER Pioneers II. xvii. 256 There will soon be no red-skin in the country.

1872 W. H. DIXON W. Penn (rev. ed.) xxiii. 205 A strong believer in the native virtues of the Redskins, when these savages were treated well.

1890 Times 27 Dec. 3/2 After dark the whole band … renewed the attack, Kicking Bear himself leading the redskins.

1922 J. JOYCE Ulysses II. xii. [Cyclops] 316 The Times rubbed its hands and told the whitelivered Saxons there would soon be as few Irish in Ireland as redskins in America.

a1939 Z. GREY Black Mesa (1955) iii. 64 Say, my redskin beauty, don’t talk Mexican to me.

1968 Manch. Guardian Weekly 17 Oct. 19 The drop-outs have copped out, the redskins have bitten the dust, the way-outs have faced the nitty-gritty (truth).

2006 Word July 121/1 Ethan wants to rescue his little girl from the clutches of a dirty no-good redskin.

2. Also redskin potato. Any of various types of potato with a red or pink skin. …

This entry for “redskin” in the online (third) edition of the Oxford English Dictionary has benefited from scholarship that traces the popularity of the term to James Fenimore Cooper who, as linguist Ives Goddard has argued, may have been influenced by translations of terms in indigenous languages in the Great Lakes region. This does not, however, mean that “redskin” should be taken as an indigenous or neutral term. As historian Nancy Shoemaker has shown, the widespread use of skin color to differentiate types of people in North America originated in the 18th century and drew from a number of influences, including indigenous color symbolism (for example, the Chero- kee’s red/white symbolism), Linnaeus’s classification of human races and the transatlantic slave trade. It also represented attempts on the parts of indigenous and colonial peoples to consolidate identity around a visible physical trait. Regardless of the complex origin of the term, it is indisputable that by the 19th century “redskin” had strong derogatory connotations. These connotations remain current, as “dirty no-good redskin,” the OED’s 2006 example, indicates. Not only does this usage exist today, but the frequent use of such phrases (in Hollywood films, for example) makes it sound familiar. The handful of examples in the OED also shows how consistently the term has been associated with treachery, warfare, displacement, extinction and sexual violence. The word “redskin” is central to the discourse that justified settler colonialism and Western expansion in the United States.

No Offense

Several decades of activism have led to the retirement of many school and college nick-names, mascots and logos on the grounds that they discriminate against Native American students’ right to an equal education. Notably, in 2005 the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) banned “hostile or abusive” imagery in postseason tournaments, leading to the retirement of many offensive mascots, including Chief Illiniwek of the University of Illinois. Professional franchises have been stubbornly resistant to charges of racism, however, and legal challenges dating to 1992 have thus far proven unsuccessful in court. Professional teams such as the Washington Redskins have dug in their heels, even as school teams are demonstrating that athletics can proceed quite nicely without racist mascots.

The anti-mascot movement, led by activists such as Suzan Harjo, has recently gained traction, with even President Obama weighing in on the Washington Redskins trademark. In a 2013 interview with the Associated Press, Obama remarked, “If I were the owner of the team and I knew that there was a name of my team, even if it had a storied history, that was offending a sizable group of people, I’d think about changing it.”

In response to this mild but newsworthy statement, the attorney for the District’s football team stated, “We at the Redskins respect everyone. But like devoted fans of the Atlanta Braves, the Cleveland Indians and the Chicago Blackhawks, we love our team and its name and, like those fans, we do not intend to disparage or disrespect a racial or ethnic group” (3). This refusal to acknowledge the offensiveness of the Redskin trademark is both a legacy of colonialism and a contemporary form of racism. As critical race theory has shown, it is not only the intent of a racist act that matters, but also its impact or effect. Those who “love” the Redskins’ name may not intend to be disrespectful, but reducing the matter to one of intent trivializes the concerns of American Indians who perceive the name as a profound societal expression of disrespect, disparagement and dehumanization.

Native American activists have sought to use trademark law to void federal registration of the Redskin trademark since 1992, soon after the team won the Super Bowl (against the Buffalo Bills, in a symbolic replay of the Indian Wars and Wild West shows of the 19th century). In 2009 the Supreme Court dismissed the 1992 case, Harjo v. ProFootball, Inc., on the basis of a technicality (the time that had elapsed between the filing of the trademark and the petition). After this a new petition, Blackhorse v. ProFootball, Inc., was filed. Brought to the US Patent and Trademark Office by five Native Americans, whose standing to file the petition was assured by their youth, this petition was decided in the petitioners’ favor by the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board on June 18, 2014. Trademark protection remains in place, however, pending the resolution of an appeal by the Washington franchise (Blackhorse v. Pro Football, Inc. Decision 2014; McKenna 2014).

Before this ruling the US Patent and Trademark Office had refused to register several other trademarks including the term “redskin” (for software, pork rinds and cheerleaders, for example), because they are derogatory slurs in violation of the Lanham Act (4). The 2013 decision to refuse to register a trademark for Redskins Hog Rinds cited several dictionaries, including the OED, which call the term “offensive,” “disparaging” or “taboo” (5). The trademark office also cites published evidence that the term is considered offensive by many Native Americans, including the National Congress of American Indians, which refers to it as the “R-word” and to the team as the “Redsk*ns.” These are useful replacements that I will use in the remainder of this article, together with “the Washington football team,” which is employed as an alternative by a few media outlets, including the Washington City Paper, Buffalo News, Philadelphia Daily News, and Slate (6).

In filing for a cancellation of the trade- mark’s protection, the litigants in the Blackhorse case included evidence from dictionaries, reference books and statements by American Indian political groups that date from the 1960s, as well as expert testimony showing a decline in the use of the R-word in print and film since the 1950s, suggesting that it was widely viewed as offensive (7). While this point may seem obvious, akin to demonstrating that the N-word is disparaging, such is the state of the debate. The complex origins of the R-word, positive uses of the word, the popularity of the word among non-Indians and the indifference among some Native Americans to sports stereotypes have all been used to dispute the clear fact that long before 1967 the R-word was a racial slur, as it continues to be today. As the National Congress of American Indians put it in their resolution in connection with the 1992 lawsuit: “the term REDSK*NS is not and has never been one of honor or respect, but instead, it has always been and continues to be a pejorative, derogatory, denigrating, offensive, scandalous, contemptuous, disreputable, disparaging, and racist designation for Native Americans” (8).

Congressional representatives have recently been working to remove what is known as the contemporary evidence bar. In March 2013, Congressman Eni Faleomavaega of American Samoa introduced the Non-Disparagement of American Indians in Trademark Registrations Act (H.R. 1278), which would amend the Lanham Act to require the cancellation of any registered trademarks that contain the R-word. Twenty members of Congress support the bill, including civil rights advocate John Lewis of Georgia, Eleanor Holmes Norton of Washington, D.C., and the co-chairpersons of the Congressional Native American Caucus, Tom Cole of Oklahoma and Betty McCollum of Minnesota. Although the bill is unlikely to make its way out of the House Judiciary Sub-committee, it is gaining public attention and represents a significant moment in the campaign to influence public opinion. Since the bill was filed, House majority leader Nancy Pelosi and Senate majority leader Harry Reid have both come out against the Washington Redsk*ns’ name, with Reid saying pointedly, “We live in a society where you can’t denigrate a race of people. And that’s what that is. I mean, you can’t have the Washington Blackskins. I think it’s so shortsighted” (9).

One Thing Native Americans Don’t Call Themselves

As lawsuits and congressional bills crawl through the system, the anti-mascot campaign has gained momentum and visibility through the use of social media and the World Wide Web. The National Council of American Indians has waged a campaign against stereotyping since 1968; 45 years later, in 2013, the Council released a report on sports mascots, supported by a YouTube video. That same year the Oneida Indian Nation of upstate New York, a group made prosperous by its casino operation, launched a more targeted effort called Change the Mascot. This initiative is focused on the Washington football franchise and, in the words of Oneida leader Ray Halbritter, on achieving a change that “lives up to the goals of mutual respect” (10). Placing the “mutual” in front of “respect” rings a salutary change on the “respect” and “honor” theme invoked by supporters of pseudo-Indian mascots and logos.

Opponents of pseudo-Indian trademarks, logos and mascots have pointed out for decades that they perpetuate racist images of a type that is no longer publicly permitted for other ethnic groups, as noted by Senator Reid. Drawing on the work of anthropologist Aihwa Ong, I would suggest that the “mascot slot” consigns American Indians to a distinctive form of cultural citizenship in which they are symbols rather than citizens bearing full civil rights. It is not surprising that the first sitting president to speak out on the mascot issue is a member of a minority group, and that the main sponsor of the bill addressing trademarks is an indigenous Pacific Islander. People who have experienced racial slurs might be expected to be more sensitive to those imposed on others. But it is in the interest of all Americans to live in a society that does not sanction the trademarking and commercialization of racial slurs. Claiming that these trademarks respect and honor American Indians and reducing the issue to what fans, players and owners “intend” perpetuate colonialist forms of representation and appropriation. Institutionalized practices of mimicry and caricature directed at a racial and ethnic group are simply inconsistent with the values of a diverse nation that values equality.

No one is claiming that the mascot issue is the most serious concern facing Native Americans today, but many see strong continuities between racist symbolism on the sports field and the existential threats that some Native Americans face. People who are habitually caricatured in public arenas suffer a form of marginalization from the public sphere that makes it all the more dif- ficult to tackle serious disparities in health, education and employment. Just as importantly, people who learn to think of American Indians as symbols of a warrior past rather than as people living in the present may have difficulty accepting Native Americans as their equals, or what anthropologist Johannes Fabian calls “coevals.”

Part of being coeval to another person or group is the ability to represent oneself rather than to be represented. As “Proud to Be,” the wonderfully effective video recently released by the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) puts it, “Native Americans call themselves many things,” including hundreds of tribal names. “The one thing they don’t. …”

Or, as a series of indigenous leaders on another persuasive NCAI video say emphatically, “I’m not a mascot.”

Notes

1. “The Absence of Native American Power,” Moyers and Company (April 9, 2013), video, accessed March 15, 2014, http://billmoyers.com/ segment/sherman-alexie-on-living-outside-borders.

2. Maud Petersham and Miska Petersham, An American ABC (New York: Macmillan, 1941).

3. Ken Belson, “Obama Points to ‘Legitimate Concerns’ over Redskins’ Name,” New York Times, October 5, 2013, accessed March 16, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/06/ sports/football/obama-enters-the-debate-on-the-redskins-name.html?_r=0; Dave Zirin, “President Obama and ‘The Onion’ Unite on Changing the Redskins’ Name,” The Nation blog, October 9, 2013, accessed March 16, 2014, http://www. thenation.com/blog/176570/president-obama-and-onion-unite-changing-redskins-name#; Julie Pace, “Obama Open to Name Change for Washington Redskins,” Associated Press, October 5, 2013, accessed March 16, 2014, http://big story.ap.org/article/obama-open-name-change-washington-redskins.

4. Theresa Vargas, “From Pork Rinds to Cheer- leaders, the Trademark Office Rejects the Word ‘Redskins’,” Washington Post, January 28, 2014, accessed March 16, 2014, http://www.washing tonpost.com/blogs/local/wp/2014/01/28/from-pork-rinds-to-cheerleaders-the-trademark-office-rejects-the-word-redskins/.

5. Letter to James Bethel, in re U.S. Trademark Application No. 86052159 – Redskins Hog Rinds – 72225, United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), December 29, 2013, accessed March 16, 2014, http://tsdr.uspto.gov/documentviewer?caseId=sn86052159&docId=O OA20131229163025#docIndex=0&page=1.

6. David Plotz, “Why Slate Will No Longer Refer to the Washington’s NFL Team as the Redskins,” Slate, August 8, 2013, accessed March 16, 2014, http://www.slate.com/articles/sports/ sports_nut/2013/08/washington_redskins_nick name_why_slate_will_stop_referring_to_the_nfl_ team.html.

7. “Fine Timing for the Washington Redskins: ‘Racial Epithets’ as Trademarks,” Latham & Watkins, Client Alert No. 1526, Litigation Department, May 22, 2013, accessed March 16, 2014, http://www.mycorporateresource.com/ index.php?option=com_content&view=article& id=131454:latham-a-watkins-fine-timing-for-the-washington-redskins-trademark&catid=1952 :trademarks&Itemid=206056. For updates on the Blackhorse v. ProFootball case, see, for example, Blackhorse v. ProFootball, Inc. Decision 2014; McKenna 2014.

8. “Ending the Legacy of Racism in Sports and the Era of Harmful ‘Indian’ Sports Mascots,” Report, National Congress of American Indians, October 2013, accessed March 16, 2014, available at http://www.ncai.org/.

9. Bob Cusack, “Harry Reid: Redskins Should Change Name,” The Hill, December 19, 2013, accessed March 16, 2014, http://thehill.com/blogs/blog-briefing-room/news/193585-harry-reid-redskins-should-change-their-name.

10. “Oneida Indian Nation Launches ‘Change the Mascot’ Ad Campaign against D.C.’s NFL Team,” press release, Oneida Indian Nation, September 5, 2013, accessed March 16, 2014, http://www.changethemascot.org/press-coverage.

Works Cited and Suggestions for Further Reading/Viewing

Alexie, Sherman. 2007. The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian. New York: Little, Brown & Company.

Alexie, Sherman. 2013. Commentary at “Adapting Ethnicity” panel. October 28. University of Texas at Austin.

Baca, Lawrence R. 2004. “Native Images in Schools and the Racially Hostile Environment.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 28 (1): 71–78.

Blackhorse v. ProFootball, Inc. Decision, 2014. United States Patent and Trademark Office. www.uspto.gov/news/DCfootballtrademark. Accessed June 20, 2014.

Cattelino, Jessica R. 2008. High Stakes: Florida Seminole Gaming and Sovereignty. Durham: Duke University Press.

Change the Mascot, in association with the National Congress of American Indians. 2014. Proud to Be. Video. http://www.changethe mascot.org. Accessed March 16, 2014.

Coombe, Rosemary J. 1998. The Cultural Life of Intellectual Properties: Authorship, Appropriation, and the Law. Durham: Duke University Press.

Fabian, Johannes. 1983. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object. New York: Columbia University Press.

Farnell, Brenda. 2004. The Fancy Dance of Racializing Discourse. Journal of Sport and Social Issues 28 (1): 30–55.

Goddard, Ives. 2005. “‘I Am a Red-Skin’: The

Adoption of a Native American Expression, 1769–1826.” European Review of Native American Studies 19: 1–20.

Harjo, Suzan Shown. 2001. “Fighting Name-Calling: Challenging ‘Redskins’ in Court.” In C. Richard King and Charles Fruehling Springwood, eds., Team Spirits: Essays on the History and Significance of Native American Mascots, pp. 189– 207. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

King, C. Richard. 2010. The Native American Mascot Controversy: A Handbook. Plymouth, UK: Scarecrow Press.

Levi-Strauss, Claude. 1971. Totemism. Boston: Beacon Press.

McKenna, Mark P. 2014. “The Implications of Blackhorse v. ProFootball, Inc.” Blog post. Patently=o. http://patentlyO.com/patent/2014/06/implications=blackhorse=football.html.

National Congress of American Indians. 2013. I Am Not a Mascot. Video. Accessed March 16, 2014. http://www.ncai.org/news/articles/2013/ 11/26/ncai-video-change-the-mascot.

Ong, Aihwa. 1996. “Cultural Citizenship as Subject-Making: Immigrants Negotiate Racial and Cultural Boundaries in the United States.” Cur- rent Anthropology 37: 737–762.

“redskin, n.” 2014. OED Online, 3d edition. Ox- ford: Oxford University Press. http://www.oed .com.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/view/Entry/160483? redirectedFrom=redskin#eid. Accessed 15 March 2014.

Shoemaker, Nancy. 2004. A Strange Likeness: Becoming Red and White in Eighteenth-Century North America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Staurowsky, Ellen J. 2004. “Privilege at Play: On the Legal and Social Fictions That Sustain American Indian Sport Imagery.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 28 (1): 11–29.

Staurowsky, Ellen J. 2007. “‘You Know, We Are All Indian’: Exploring White Power and Privilege in Reactions to the NCAA Native American Mas- cot Policy.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 31(1): 61–76.

Strong, Pauline Turner. 2012. American Indians and the American Imaginary: Cultural Representation Across the Centuries. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. 1991. “Anthropology and the Savage Slot: The Poetics and Politics of Otherness.” In Richard G. Fox, ed., Recapturing Anthropology: Working in the Present. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press, 17–44.

Pauline Turner Strong is professor of anthropology and gender studies at the University of Texas at Austin. A cultural and historical anthropologist, her research centers on representations of Native Americans in American public culture, including narratives, films, exhibits, sports, scholar- ship, legal discourse and informal education. She is the author of American Indians and the American Imaginary: Cultural Representation across the Centuries (Paradigm, 2012) and Captive Selves, Captivating Others: The Politics and Poetics of Colonial American Captivity Narratives (Perseus, 1999), among other works. As director of the University of Texas Humanities Institute, she develops interdisciplinary humanities pro- grams for students, faculty and the community.

One Response

I believe it comes down to racism and greed. The land and story of Native cultures with their symbols and sacred places have never been respected. The cultural genocide will never be healed and the billions in restitution in Canada and the USA will never be paid. I think all of the Native symbols in professional sport should stop.