In a small village in eastern Uganda, I sat on the porch of my host’s home. A retired head teacher, he has a rumbling, stentorian voice that commands authority. As we sipped tea, he looked over at me and asked: “Is it true that in your country it is legal for a man to go with a goat?”

After a moment, I sputtered, “Well, no!”

He considered my answer. “But it is legal for a man to go with a man?”

I told him “Yes.”

He continued, “And for a woman to go with a woman?”

“That too,” I said.

He didn’t seem shocked or disgusted. He struck me, rather, as utterly mystified. Our awkward silence was broken when the children start arriving home from school—at least 20 of them who ranged from mid-teens to teeny tiny. Their parents, sons and daughters-in-law of my host, occupy their own huts in this compound or nearby. As each child arrived, he or she came and sank down on both knees, offering a hand from this kneeling position. This traditional greeting was performed for each adult in the compound.

***

Since my arrival in Uganda in late January, the news both in and out of the country has been dominated by discussion of two controversial laws, one declaring homosexuality illegal, and the other an anti-pornography law that has somehow been interpreted as an anti-miniskirt law. Both laws are draconian, mean-spirited and wrong-headed. Despite this, however, Uganda strikes me not as a country full of bigotry and violence, but rather as a deeply conventional country that is facing—like much of the global south—rapid and destabilizing changes to its society. Blessed with fertile soil and abundant rain, huge swathes of verdant land have already been taken for corporate-owned tea and banana plantations. Now that the carbon credit market is heating up, so to speak, foreign interests are busy planting pine forests to earn themselves some environmental points. Pine trees, it turns out, are excellent at absorbing carbon dioxide and emitting huge amounts of oxygen. They are not, however, native to the equatorial tropics; they ruin the soil permanently, and are among the reasons that the peasant farmers who constitute the overwhelming majority of Uganda’s population are increasingly without land or means of livelihood. To the west, oil has been discovered, disrupting land ownership there. China is busy building sleek highways in that direction, providing infrastructure in exchange for access to precious resources. In the north, where conflict seems never to abate, scuffles between anti-government forces are hard to tell from the bleed-over from what looks more and more like civil war in South Sudan.

In these and so many other instances, foreign imperatives and agendas come together to make most Ugandans’ lives much more complicated and miserable than they otherwise might be. With a government that depends for the bulk of its budget on foreign aid, the degree to which the nation is indeed sovereign seems just a tad in doubt. President Museveni, who has held power for 27 years, must take pains to assert his control. On one side, he has to deal with a parliament whipped into a frenzy with drafting these silly laws, now including one punishing people for “willful” transmission of HIV. On the other, big brother-y interests such as the United States and the IMF threaten to put a choke hold on the economy if he enforces the anti-gay laws (apparently the anti-pornography law is not disturbing enough to the international community to warrant a response). What’s a despot to do?

It is in this context that the anti-homosexuality and anti-pornography laws seem perhaps less about punishing specific people and more about asserting some sort of Ugandan independence. In fact, there are pockets of people who argue—either separately or together—that homosexuality, miniskirts and evangelical Christianity are all colonialist imports to Uganda that ought to be stamped out. As one friend remarked to me, “and THAT interpretation is just twisted enough to make a liberal think twice!” It certainly seems quite clear that the emergence of the government’s obsession with homosexuality can be traced to evangelical Christians from the United States, who have been hard at work for some time on spreading their ideas abroad. In particular, their efforts center around making homosexuality the object of legislation; anti-gay violence is the not-so-surprising side effect. Now, there is no doubt that Uganda is not exactly a gay-friendly country. On the other hand, absent the efforts of these extremist and hateful Christians, homosexuality previously was not a particularly hot-button issue. Nor were miniskirts, although it is true that women can expect quite a bit of pawing, ogling and other unpleasant reactions from men if they wear tight or revealing clothing in public places. What appalls me most about the situation is the degree to which so many everyday Ugandans—gay and straight—end up suffering for other peoples’ self-serving agendas.

***

It is worth remembering that in the small villages where most Ugandans live, daily life is not characterized by the smorgasbord of lifestyle and consumer options that typify the urban cosmopolitan setting. In the 1980s when I worked at an upscale grocery store in New York’s Greenwich Village, for example, there was a customer who routinely came in dressed as a clown. She was not a professional clown stopping in after a birthday party gig. She was a woman who dressed like a clown in her daily life. In New York, in “the Village,” nobody bats an eye at that kind of thing. In the Ugandan village, distinctions cut much finer. Children looked at my palm and asked, “Do you dig? Your hands are so soft!”

So as not to appear utterly lame, I said, “Well, I can dig, but where I live we don’t dig.” “Why?” asked one person in shock. I answered that in the United States, many people have no land to dig.

“You mean where you come from you don’t have inherited land?” another inquired in disbelief.

At home people tend to classify me as extremely fit and lean. Here in the village, where my body and hands are “soft,” I suddenly realized that the villagers think I’m laughably weak. This helps to explain why they keep discouraging me from walking anywhere. They think I’m simply incapable. When I also managed to mention that I do not know how to make bricks or build a hut or thatch it, they quickly seemed to decide that I’m deficient, a simpleton. The truth is, they’re right. In their world, I am pretty useless. I can’t carry water, I don’t know how to cook millet bread or roast sorghum, and I certainly can’t dig.

My host rumbled again. “You are at the junior home, you know.” After a pause he continued: “Yes, I must admit it, I am a polygamist.” Since I’m an anthropologist, I’m not especially shocked. I know about these kinds of kinship arrangements. As a middle-class parent from the United States, however, I found myself wondering how he can afford to have all those kids, and concluded that he can’t “afford” them. With two wives and more than a dozen children, my host will be unable to provide each of his sons with enough land for sustenance. Let’s not even think too hard about the daughters, who will be married off. Uganda’s population is the youngest in the world, and in the city where culture wars are raging about miniskirts and the expression of sexuality, hundreds of thousands of young people who have had to leave their villages scramble for a living in Kampala’s slums, most earning less than $200 a year.

I have come to the village because my pal, whom I call “my main man Mike,” is one of those young people. Mike calls my host “my other dad,” which is to say, he is Mike’s uncle. Like my host, Mike’s father is a polygamist. Mike’s mother is the junior wife, and his father educated the senior wife’s children much more thoroughly than those of the junior wife. Though several of the senior wife’s children were sent to university, Mike’s education finished with high school. Mike’s mom was routinely beaten mercilessly by his dad, and five years ago she took her young children and left to work her own father’s land a few kilometers away. She’s been on her own ever since. Mike helps her out when he can, but he earns 100,000 UGX a month, less than $40 USD. At 23, he has been living on his own for the last two years in Kampala, sharing an 8 x 10-foot room with a good friend. One boy is a Christian, the other a Muslim. One works nights, the other days, and in this way they can easily share the room’s one twin-sized bed. Working as a security guard, Mike puts in six 12-hour shifts a week. When we met Mike’s dad, up at the senior wife’s compound, the larger part of me wanted to haul off and give him the what-for. Standing next to his father, Mike beamed and said, “I like him so much!” I have to admit, I cannot imagine why; I privately decide to like him not one bit.

In the apartment where I stay in Kampala, the nearby evangelical church manages to blast its sermons out at the same time as the local mosque is broadcasting its call to prayer. I doubt the timing is accidental. In terms of the annoyance factor, the evangelicals win, hands down. Most nights they blare their salvation from their blown-out speakers until well after two in the morning. What happened to swords into plough-shares, I wonder. The distorted sounds of their salvation assault the neighborhood nightly. I’m rankled at the busybodies who seek to impose their ideas on Uganda, on gays, on anybody. I’m jaggedly raging at Mike’s dad, who has picked and chosen among his kids, as all fathers of so many children inevitably must. I’m frustrated that Uganda appears to the rest of the world a scary backwater with nothing much better to do than pass insane laws.

Margaret Mead once said that “the best society is one where every human gift is valued.” Are beliefs that lead to violence and injustice also in some way human gifts? How do we breach the distance between our own ways and the ways of others that we might find profoundly disturbing? I am among those who yearn for a world in which all gifts might be valued, but I struggle to learn the difference between a gift and a curse. Mike wants his mom to go back and live in his dad’s compound. To me, that makes about as much sense as it being legal for a man to go with a goat. Mike, meanwhile, calculates how much money he will need to build his mom a small house in the compound. “I will build the walls of mud,” he muses. “I wanted to be a high school teacher. But that dream has disappeared.” As I glower, Mike smiles and laughs and holds no grudges. “That’s just life,” he says.

Note

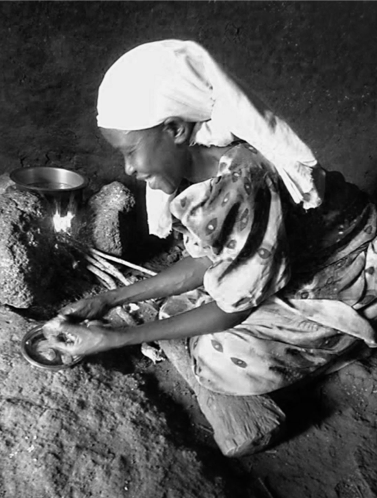

Photos by Elizabeth Chin.

Elizabeth Chin joined the faculty of Art Center in 2011 as a founding member of the Media Design Practices/Field program. As an anthropologist her practice includes performative scholarship, experimental writing and collaborative ethnography. Her book Purchasing Power (Minnesota 2001) was a finalist for the C. Wright Mills Award. In 2007 she won the AAA/Oxford University Press Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching of Anthropology.