Beginnings

Forged by glacial flows millions of years ago, the San Juan Mountains in southern Colorado remain a mystical landscape to many visitors. The lure of their sky-bound rocky spires, regionally called “fourteeners,” a colloquial title that references their higher-than-14,000-foot elevation, draws thousands of tourists annually to explore nostalgic remnants of the “wild west” in the form of historic trains and mining tours. Silverton, with a population of 650, is the only town in the mountainous San Juan County in Southwestern Colorado. Although mining operations in the region formally ended in 1991, the legacy of extraction continues to feed a tourist economy of over 100,000 annual sightseers. Thus, the entire town has since been designated as a National Historical Landmark site. Nostalgia for an imagined frontier is seemingly as monumental as the surrounding landscape.

Growing up in Western Colorado beneath the shadow of another insidious industry, that of uranium extraction, I was familiar with the Ute name Uncompaghre. Only years later, however, would I understand its meaning or visit the places that gave it life. I learned that Uncompaghre means “red water spring.” The tallest summit in the San Juan Mountains is Uncompaghre Peak, perhaps for the once plentiful hot water springs that flow in nearby Ouray, Colorado. Like Uncompaghre or Ouray, there are dozens of places named by or for the original Ute inhabitants of these territories. Such naming, however, does not depict a reverential history.

The first ore brought up from the granite depths of the Silverton Caldera in the early 1870s effectively legitimized the violent removal of Utes from their homelands located in the San Juan Mountains. The General Mining Act of 1872 laid the framework for settler colonial land seizure. The final blow of this expropriation was sealed with the Brunot Agreement of 1873, which facilitated the “opening” of territories through a legal sleight of hand that was orchestrated with the supposed blessing of Ute nations. Processes of eviction and extraction came hand in hand. Hundreds of mining claims, including one made to the now infamous Gold King site in 1887, would be staked as settlers arrived.

Following the arrival of the Denver & Rio Grande Railway line to Durango in 1881, the railroad began meandering northward to the heart of the San Juan Mountains, eventually reaching the valley where a mining camp called Silverton would be incorporated in 1885. Along this wandering course, the narrow-gauge train line repeatedly traverses the Animas River, a tributary of the larger San Juan River.

Unsurprisingly then, many regional locales are named for water. For example, Páa means water in the Ute language, and this title appears in several place names through-out the region. Yampa. Pagosa Springs. Even Uncompaghre and its “red water spring” translation. Similarly, the state name Colorado is translated from Spanish to mean a “reddish color,” which refers to the ancestral Río Colorado and the traces of red silt that its waters routinely stir. Today, however, the flowing mountain waters have come to be referenced for another vivid color representing the slow violence of environmental contamination: yellow.

Ruptures

On the morning of August 5, 2015, a group of Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) subcontractors working at the abandoned Gold King Mine on Bonita Peak ruptured a retaining wall. A mine reinforcement project became an incipient disaster as metal-laden acidic water gushed into Cement Creek below. Three million gallons of arsenic, lead, cadmium and other metal sulfides rushed into the mountain stream. By the afternoon, the yellow plume had reached Silverton. Curiously, the sight of mustard-colored water seemed to be a regular occurrence. An employee at the local museum would later tell me that the water had always appeared characteristically yellow, just in different degrees. As we talked, I noticed books about San Juan mining and boomtown saloons, about ghosts and local lore, sitting on the gift shop shelf. She clarified further, “as long as I have known, there have never been fish in that water.” Always yellow. Never fish. And just like that, I realized that toxic mine drainage was normalized there. This was not so for downstream communities.

In the hours that followed the rupture, EPA officials scrambled to control the situation, but an official press release would not be distributed until midnight approached. This breach of time, like that of the bulkhead wall, would haunt federal officials for months to follow. On the next day, August 6, news began to spread. I found out about the spill from friends on social media after the plume had entered the Animas River and reached Durango. The widely circulated photograph of three kayakers at Baker’s Bridge suspended in an orange murky soup became symbolic of a kind of relationship that locals had with the river. The so-called “tang” color that indexed bygone eras of mining became entangled with the present recreational activities that sustained the local economy today. But absent from this image was another set of relationships that would exceed the imagination of Western legal and regulatory structure. From further downstream, I bore witness to the spill and the lingering traces of its rupture.

Waiting

Tethering Internet at my grandparent’s home in the Navajo Nation capitol of Window Rock, Arizona, I watched the mounting anxiety being shared via photo posts and local news accounts. The plume, whatever this phantom object was, would soon move across state lines. Traveling south into New Mexico, the Animas converges with the San Juan River in Farmington — a place referred to in the Diné language as Tótah, meaning “between the waters.” Before Euro-American settlement, these waters sustained life for myriad Indigenous communities living along its banks and watersheds. Today, a common phrase proclaimed by Diné activists is Tó éí ííńá át’é, which translates to “water is life.” This refrain points to the importance of water not only for daily sustenance, but also as a sacred entity crucial for our survival as Indigenous peoples.

One by one, irrigation gates were shuttered for Diné communities along the San Juan River: Upper Fruitland; Nenahnezad; San Juan; Tse Daa K’aan; Shiprock. Fields of corn, melon and squash began to wither. Emergency water tanks were delivered to offer a bit of relief. But farmers, in horror, quickly discovered the oily residue in the tanks were the same substance extracted from the earth. After all, the oil and natural gas industry has been rapidly proliferating again in the carbon-rich San Juan basin. Their toxic reach is both everywhere and nowhere, a presence that permeates, haunts and conceals. On a westerly course, the yellow water continued through the Navajo Nation before eventually dissipating into Lake Powell.

The following week in Shiprock, New Mexico — the largest Diné farming community along the San Juan River — I attended a public information meeting about the spill. The heat lingers dry and heavy as I come upon the community auditorium. I find a space for my car on the weedy roadside where several dozen other vehicles, mostly trucks, are parked since the lot is full. The busy ambiance reminds me of the annual tribal fairs I grew up attending, where families would stake out spots along the parade route. Truck beds and drop-down gates would serve as platforms for optimal viewing and candy catching. But today, the air hangs only with trepidation.

Once inside I found the space filled with farmers, concerned citizens, journalists, and students. Everyone demands answers. “Do not contaminate our farms!” “What is in the water? I don’t want my children to be sterile.” “What is going to happen when we get sick?” “If you can’t clean it up, don’t say that you can because this water is dangerous and it causes cancer.” In response, Navajo Nation officials show graphs of water contamination levels hoping to reassure community members about this evidence for pending litigation, but these answers do little to satisfy public concerns. “When will we be able to farm again?” someone yells. Nobody knew at the time that irrigation channels would remain closed for nine months, only to reopen the following spring.

That day and during the several meetings to follow, there were many questions posed but few answered, at least the answers the public wanted to hear. Almost immediately after news of the spill broke, state environmental organizations, universities and tribal agencies assembled teams to sample the soil and water. Soon, the spill revealed as much about the present fissures in bureaucracy and jurisdiction as it did about the fragmentation of Indigenous territories that first occurred when the mines were built. Both continue to reveal the perils of private capitalist industry and state oversight that have functioned without accountability to this land, its people and their histories.

Returns

In the subsequent months, while living in the Puerco Valley of Northern Arizona where I was doing research on uranium contamination, I continued to follow the Gold King mine spill and its aftermath. Increasingly, my personal and research responsibilities converged through water; I became more involved in community education and advocacy work with the Diné group Tó Bei Nihi Dziil (Water is Our Strength). Together, alongside researchers from the Navajo Gold King Mine Spill Exposure Project, we worked to host several community teach-ins designed to share and solicit information about the spill.

Through these regular meetings, I also met new relatives, for my maternal grandmother was raised along the San Juan River. She attended a boarding school in the nearby border town of Farmington, New Mexico, but this undesired arrangement gave her little time to spend with her family. It was another example of a rupture that continues to reverberate across generations. I too continue to feel these ruptures. The extractive force of federal Indian policies and the blunt blows of contamination caused by industries staked in the westward push of expansion continue to hit us again and again. But it is also through the water, Tó, that connects and reaffirms our relations.

In these spaces and places, I was reminded how the San Juan River is considered a male relative, while the earth is female. In the aftermath of the spill, we confronted the challenge of how to steward this balance through the violence of repeated contamination. As regional sample results, which indicated that the river had “returned to pre-spill” conditions within weeks of the incident, were released, local anxieties were not easily assuaged. What does it mean when a baseline starts from a point of existing contamination? This is the enduring condition of settler colonialism. In public meetings, I heard several farmers speak of their customers’ hesitance when they attempted to sell them the produce that they had been able to save before the water shut off. Some said they could not even sell their tádídíín, the yellow corn pollen used for ceremonial purposes.

There have been spills before, like the one back in the 1960s from a Kerr-McGee uranium and vanadium processing facility that sat precariously above the southern banks of the San Juan River. It closed in 1968, but the area would not be cleaned up until the Navajo Nation entered into an agreement with the Department of Energy in 1983. After the Gold King mine spill, some feared that the yellow discharge was yet another uranium spill or even something akin to the Vietnam era herbicidal weapon known as “Agent Orange.” For several Shiprock area farmers who served in Vietnam, this was not an abstract concern. They spoke about the trauma of boarding schools and later, the war.

There were others who bemoaned the effluent from upstream Farmington or the presence of commercial agricultural runoff. There were also concerns regarding wind-carried contamination originating from Four Corners Generating Station, the off-reservation coal-fired power plant, or from the fracking sites multiplying throughout the region. I began to ask myself, what does toxic contamination even look like? The material forms are numerous and insidious. Moreover, how can we visualize and document such toxicity?

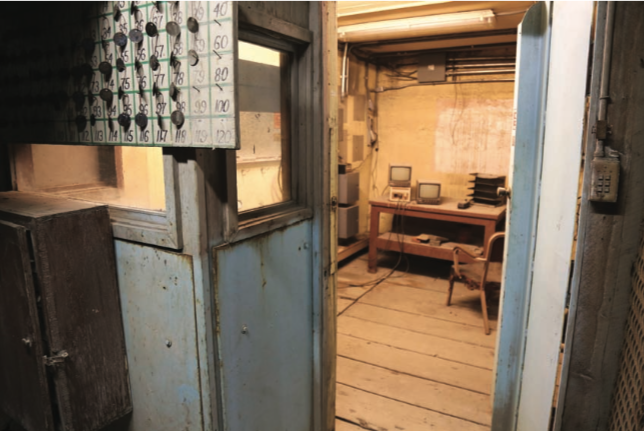

One year after the Gold King Mine Spill, in August 2016, I embarked on a road trip from Silverton, Colorado, to Shiprock, New Mexico, to follow the path that the yellow discharge had traveled. Through my photographic journey, I make explicit the enduring presence of toxicity in forms both seen and unseen. Sometimes it appears sublime, other times haunting. The images in this article and that follow highlight the relationships that various communities sustain through water/tó/páa despite the occurrence of repeated and enduring contamination. The Gold King Mine Spill shows us this, even in that, which cannot be readily seen.

Acknowledgments

I would like to recognize the ongoing collaboration, called the Navajo Gold King Mine Spill Exposure Project, between the University of Arizona and Diné collective Tó Bei Nihi Dziil. Ahe’hee’ to Janene Yazzie for her partnership on this and other important water security projects across the Navajo Nation. Thank you as well to Angelo Baca and Shonie De La Rosa for their camera assistance during portions of the Gold King Mine Spill multimedia project, Tó Łitso/The Day Our River Ran Yellow, which is shared in this essay. Last, thank you to William Lempert and to the editors of this journal for providing helpful feedback on the narrative and photo selection.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Boyles, Traci Brynne. Wastelanding: Legacies of Uranium Mining in Navajo Country. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

Liboiron, Max. “Bibliography on Critical Approaches to Toxics and Toxicity.” Discard Studies. Accessed July 10, 2017. https://discardstudies.com/2017/07/10/bibliography-on-critical-approaches-to-toxics-and-toxicity/.

“Life on the Frontier: The Environmental Anthropology of Settler Colonialism.” Engagement. A blog published by the Anthropology and Environment Society, a section of the American Anthropological Association. Accessed July 10, 2017.

https://aesengagement.wordpress.com/thematic-series/life-on-the-frontier-the-environmental-anthropology-of-settler-colonialism/.

Thompson, Jonathan. “Silverton’s Gold King Reckoning.” High Country News, May 2, 2016. Accessed June 14, 2017. http://www.hcn.org/issues/48.7/silvertons-gold-king-reckoning.

The University of Arizona Superfund Research Program. “Gold King Mine Spill.” Accessed June 14, 2017. https://superfund.arizona.edu/info-material/gold-king-mine.

~~~

Teresa Montoya (Diné) is pursuing a doctorate in anthropology at New York University, where she also earned a certificate in culture and media (2015). She holds a master’s degree in museum anthropology (2011) from the University of Denver. Currently, Montoya is working on a multi-media project, The Day Our River Ran Yellow/Tó Łitso, a Diné centered visual meditation on the landscapes and waterscapes affected by the Gold King Mine spill in August of 2015. Themes of environmental contamination and settler colonialism raised in this project are central to her dissertation research that engages issues of jurisdiction and regulation alongside articulations of sovereignty for Diné communities confronting various forms of toxic exposure in the Navajo Nation. Montoya’s doctoral coursework and research have been generously supported by funding from New York University, the Ford Foundation, the Wenner-Gren Foundation, and the National Science Foundation. She is currently a 2017–2018 Andrew W. Mellon Native American Scholars Initiative Fellow at the American Philosophical Society.