On a hazy June afternoon in 2003, we stood on a bluff overlooking the New River in Whitethorne, Virginia with members of the newly formed Kentland Historic Revitalization Committee. The group had convened to curb a record of benign neglect in the historic district of Kentland Farm, the agricultural research station of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech). Among those present were Susan Fleming-Cook and Tamara Kennelly, who were both representing the university archives and engaged in an ongoing documentary project concerning the relationship between Virginia Tech and local under-represented populations. There were Oscar Sherman and Alex Jones, residents of Wake Forest, a nearby African American community, and local historian Jim Price. Jones and Sherman’s presence was crucial; they were there to help identify the location of the slave cemetery that was known to be located somewhere on that bluff. Both had memories of rough-hewn limestone markers on graves. After pointing out the boundaries of the area they remembered as the burial ground, Jones and Sherman looked toward the bottomland across the river and reminisced.

“Monkey Shoals,” uttered Sherman. “That’s what we used to call it. We’d be working down on that bottom and them heat monkeys [visible waves resulting from heat rising from the ground] would start coming off the railroad tracks.” Both men had either worked as hired hands on that land or their families had briefly leased the land for their own crops. Jones shared a similar memory and made a reference to a time when the land across the river — occupied since 1940 by the Radford Army Ammunition Plant — was nothing but farmland. Viewing the arsenal reminded the men of the contrast in livelihood and race relations that each had experienced after leaving that community and serving in World War II. At that moment, they were articulating an exclusive relationship to that place and by extension, claiming ownership of the impending project to re-claim and commemorate the slave cemetery.

Our initial trip to the site with Oscar Sherman and Alex Jones was exploratory. Over the next year we held a number of community meetings with residents of the Wake Forest community, largely organized by church elders, and solicited their ideas about how to address the very existence of the “slave cemetery,” as some African American historical venues in the state discourage references to slavery. Fortunately, support for some kind of commemorative project was overwhelming, and resulted in a community resolution presented to the Virginia Tech administration that called for a cursory archaeological survey and attendant research to verify the location. The key portion of that resolution was adopted for the marker commemorating the cemetery, which was erected after the initial survey.

WE, THE RESIDENTS OF WAKE FOREST

BEING LARGELY DESCENDED FROM THE SLAVES OF KENTLAND PLANTATION,

WHOSE LABOR, SKILL, BLOOD, SWEAT, AND TEARS,

ALTHOUGH THEY WERE HELD IN BONDAGE AGAINST THEIR WILL,

BROUGHT KENTLAND INTO EXISTENCE AND KEPT IT ALIVE,

AND WHOSE MEMORIES ARE STILL ALIVE ON THE LAND.

This proprietary expression of private heritage framed the trajectory for the community’s future stewardship of the site, and for autonomous initiatives within the community.

***

Virginia Tech acquired Kentland Farm in 1989 through a land exchange with a local developer. While the farm is best-known as southwest Virginia’s largest antebellum plantation, it has hosted nearly 10,000 years of human activity. Late Archaic groups once lived along the bluffs, which following the Ice Age, constituted the banks of the New River. Late Woodland cultures lived in virtual cities along the bottomlands, and by the time the first German settler arrived in the 1740s, the well-travelled road system following natural fords in the river became the main route of the Shenandoah Indian Road, the forerunner of the Wilderness Road.

The Kentland Historic Revitalization Committee’s broad goal was to develop an interpretive plan that would accentuate all cultures and historical epochs embedded in that space, with particular emphasis on those most underrepresented. That meant confronting the antebellum legacy. The original plantation proprietor, James Randall Kent, had the disquieting distinction of being the region’s largest slaveholder — claiming ownership to as many as 300 slaves by some accounts. Bondage had an unanticipated impact on the farm, as slaves incorporated West African architectural standards into some of the structures, including the six-sided smokehouse and possibly some of the slave quarters that were torn down in the mid-20th century.

After the Civil War a core of former Kentland slaves acquired land approximately two miles from the plantation, which became the community of Wake Forest. The history of that community is remarkable in that the post bellum economy quickly became one of part-time farming and full-time coal mining for black and white residents of the valley, and the mining industry actually offered a degree of respect and autonomy for African Americans that were most unusual in the pre-integration South. African American families owned at least two local mines at one point, and both employed local whites. It was most important for us to illuminate this history and to pay particular attention to the profound role that African descendants played in the history of Kentland.

Virginia Tech’s acquisition of Kentland Farm was not made with historic and cultural preservation in mind. It was intended as a working research farm, and it was clear from the beginning that negotiating a community-driven historic revitalization project would require considerable diplomacy.

Negotiating the Public Domain

Collaborative ethnographic endeavors, although ideally intended to equalize power relations between anthropologists and research communities in the process of project conceptualization and representation, are never absent complex power struggles, however subtle. When archaeology is brought into the equation — with its purported stewardship of the past and potential to unearth human remains or other culturally-sensitive artifacts — the power dynamics can become more pronounced and potentially volatile, as Sonya Atalay points out (1). Fortunately, recent projects and relationships in the realm of community- based/collaborative archaeology have forged critical models for appropriate communication and power-sharing with indigenous communities and other “descendant communities,” notably African American. The principle of power-sharing cannot be overemphasized, for as Atalay argues, it can reveal “the underlying complexities and layers of power that exist in the real world. These layers are silenced when a single archaeologist holds power and makes the decisions” (2).

As we set out to explore ways to accentuate African American history, and to eventually articulate an interpretive plan to that end in the Kentland historic district, we needed greater community support. What was at stake was not merely a power dynamic concerning historic/cultural interpretive authority or ethnographic representation, but a matter of restricted access to state property on the part of those whose history was most profoundly embedded in the land. Verifying and in some way marking the location of the slave cemetery seemed the logical first-step in addressing a sensitive historical issue.

Archaeology, Ethnography and History

The collaborative vein of archaeology has been much shaped by the emergent pursuit of indigenous archaeology, which Colwell-Chanthaphonh and his collaborators describe as “an expression of archaeological theory and praxis in which the discipline intersects with Indigenous values, knowledge, practices, ethics, and schedules, and through collaborative and community-originated or directed projects, and related critical perspectives” (3). Given the ethnographic component of our project, we also took a cue from Eric Lassiter’s succinct, foundational definition of collaborative ethnography as “an approach to ethnography that deliberately and explicitly emphasizes collaboration [with community co-intellectuals] at every point in the ethnographic process without veiling it” (4). This set of principles guided our treatment of the archaeological record of the enslaved peoples of Kentland, and the project has gradually become an exclusive matter of community conservatorship. The excavations and subsequent discussions concerning interpretation and preservation of sites and artifacts have comprised the nexus of interactions among three groups: community residents whose history is most profoundly embedded in the land and material relics; researchers and students concerned with civic duty and pedagogical principles based on democratic dialog; and state officials (through the university) who claim a legal but not necessarily ethical proprietorship over the space in question. While the role of each party is worth noting, our focus here is primarily on community empowerment.

At some point in the past 30 years, a previous owner of the farm pushed away the limestone markers that are said to have marked slave graves. Nonetheless, awareness of the cemetery remained fixed in community knowledge. Oral histories from Wake Forest families and other community residents placed the slave cemetery on top of a prominent ridge north of the plantation house. Their accounts described graves marked by roughly shaped stones amid grass and trees enclosed by a fence. Bordering the west side of the cemetery was the intersection of two fence lines that divided the rolling terrain of the farm and controlled the movement of livestock. Although local knowledge of the cemetery was apparent, some authors of Kentland’s history, and some university representatives familiar with the farm, remained unconvinced be- cause the ridge no longer holds physical evidence of a cemetery. In addition to the grave markers, trees had been removed and fences dismantled. For many years, crops of hay covered the ridge and hid the cemetery.

Local historian Jim Price, who served on our committee, drew a map of the cemetery based on recollections of Frank Bannister, a late Wake Forest resident. Alex Jones and the late Oscar Sherman, who served on the committee until his death in 2005, were among other Wake Forest residents who expressed knowledge of the cemetery. In their youth, they saw the cemetery and learned its history from grandparents who were enslaved at Kentland in the 19th century. E.O. Sheppard also remembered mowing grass in the cemetery more than 60 years ago, when his family worked Kentland’s fields as tenant farmers. All these men placed the cemetery on the same ridge, but in slightly different locations. Two remembered it at the southern edge of the ridge, while the other two pointed to an area about 80 meters north. Guided by these accounts and other oral histories collected from local residents, our search became more focused.

The next step in confirming the cemetery location involved study of 20th-century aerial photographs and quadrangle maps. Although photographic scales precluded visual confirmation of a cemetery, the aerial photographs clearly depict a small grove of trees conspicuous in the cleared agricultural fields on the ridge. Also visible in the photographs was the intersection of two agricultural fence lines along the western side of the grove. The locations of these fence lines matched those marked on the quadrangle maps. This information corroborated oral histories, which placed the cemetery on the south part of the ridge. Final confirmation of the cemetery required archaeological excavation.

An archaeological study of the cemetery was proposed and discussed during a series of meetings with representatives of the university and Wake Forest. State law mandated university consent before archaeological investigations could take place at Kentland. Moreover, the consent and support of the Wake Forest community was a prerequisite. After careful consideration, the Wake Forest community decided to support the cemetery investigations under the conditions that buried human remains would not be disturbed and disruption of the cemetery landscape would be minimized. With a signed petition of support in hand, Wake Forest requested archaeological investigations of the cemetery and the university agreed.

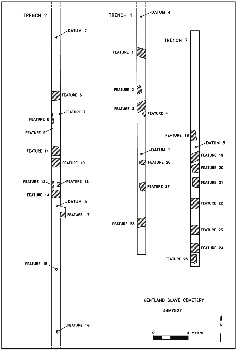

Subsurface excavation methods relied on exploratory trenches oriented in a north to south direction to increase the likelihood of intersecting evidence of grave shafts which were commonly oriented west to east. This nonintrusive method allowed us to verify the location of the slave cemetery by identifying grave shafts without disturbing the buried human remains and minimizing disturbance to the cemetery surface.

Oral histories isolated two potential areas on the ridge, so exploratory trenches were placed in each area. Assisted by university students, members of the Kentland Revitalization Committee carefully monitored the mechanical excavation of approximately one foot of topsoil from each of four trenches. Following removal of most topsoil, the bottoms of each trench were smoothed with hand tools and carefully inspected for soil changes indicative of grave shafts.

Exploratory trenches in the northern area of the ridge uncovered evidence of an agricultural field — a layer of plowed soil, evidence of previous fence posts and “scars’ left in the sub-soil by the tips of plowshares. There was no evidence of any burial or cemetery. However, both trenches in the southern part of the ridge contained evidence of graves and wooden posts for the fence enclosure. This area corresponded to the location of the small grove of trees depicted on the aerial photographs. Grave shafts were identified as bands or rectangular areas of dark, mixed soil offset against the lighter, yellow brown sub- soil.

At this point, the Kentland Revitalization Committee informed the Wake Forest community and the university administration that the cemetery location had been confirmed. Wake Forest residents immediately gathered at the cemetery to witness the graves of their ancestors and reaffirm the link between their lives and the lives of their ancestors. This emotional reunion of generations bonded by a shared Christian faith was commemorated through a reflective and solemn prayer service. Afterward, the university administration announced its respect for this sacred place and its decision to protect it from any disturbance.

University administrators also approached Wake Forest and the Kentland Revitalization Committee to request a continuation of archaeological investigations because information regarding the size and boundaries of the cemetery would facilitate and enhance its long-term protection. The committee met with the Wake Forest community and reviewed possible courses of action, ranging from no further work to full documentation of the entire cemetery. During community meetings Wake Forest residents reached a consensus decision to support additional investigations of the cemetery, but limited additional excavation to the level necessary for a confident estimate of cemetery boundaries. Additional trenches were excavated the following year until we could determine the cemetery boundaries, and the university agreed to protect the cemetery along with a surrounding buffer of land.

It is important to note that until the initial excavation of the grave shafts, Wake Forest residents’ endorsement of the project, although uniform, seemed reserved. Perhaps the tangible evidence confirming community tradition catalyzed a new and enthusiastic movement. Immediately following the 2004 excavation local residents Howard and Jean Eaves became Wake Forest’s representatives on the Historic Revitalization Committee and they spearheaded efforts to raise funds for a monument. Subsequently, they encouraged us to conduct pilot excavations on the site of the slave quarters (beginning in 2006), in which Wake Forest residents participated extensively in the physical work.

The excavation of the slave quarters site was initially motivated by our interest in investigating West African influence on architectural features of antebellum structures. Most notably, the smoke house was a six-sided structure that seemed to reflect West African taboos against corners, and there are documented examples of slave quarters that were built in this fashion elsewhere (5). The proximity of the slave quarters to the smoke house, along with recollections of at least two elders from Wake Forest and another nearby community, suggested that other structures were of the same shape. While our archaeological survey of the site was inconclusive, the participation and future response of Wake Forest residents was most significant.

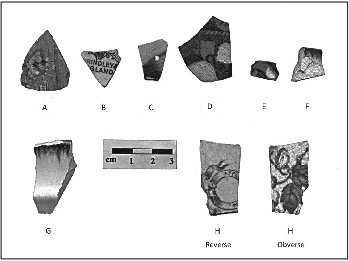

Unearthing material culture other than human remains was tantamount to discovering lost community heirlooms. More Wake Forest residents were present during that excavation than any previously, and they assumed a tacit authority in the process. And as we pondered the question of stewardship and curation, Howard and Jean Eaves simplified things for us by initiating an effort to establish a Wake Forest community museum.

***

While collaboration is far from a universal norm in museology, it has seized the ethical trajectory in much of museum anthropology over the past two decades. According to Lainie Schultz, a museum that truly embraces collaborative principles “must be an agent of empowerment for marginalized communities by providing them access to resources and it must serve as an intermediary between local groups and museum society…” (6). In our case, determining who or what constituted “museum society” became the focus. Thinking about historic interpretive initiatives in the Kentland historic district, we had originally envisioned a museum component , that would include artifacts of African American history. At the same time we acknowledged that the ethical proprietorship of these artifacts belongs with the descendant community. What has ensued, and is still evolving, is a sort of power-sharing arrangement, in which the community makes decisions.

The slave quarter excavation catalyzed the creation and opening of the Wake Forest Museum in the community’s old Holiness Church building. This community-focused project is not directed by state archaeologists and well-intentioned university diplomats. While the Wake Forest Museum is only open for annual community gatherings or occasional tours, it serves as repository for a unique collective history — an expression of private heritage. Community residents, usually Howard and Jean Eaves, and occasionally the eldest matriarch of Wake Forest, Esther Jones, provide mobile displays for events on Kentland Farm and other local venues, but only when the artifacts are accompanied by living residents — descendants of the original owners — and presented in the context of post bellum and contemporary community life. Although Kentland artifacts are technically state property, the committee recently negotiated an agreement that allows the museum to hold the artifacts on extended display. While still experimental, this practice embraces a central principle of collaborative museology. As Trudy Nicks points out, truly collaborative exhibits must “make explicit the agency with which [colonized and underrepresented] peoples have always engaged their own and other worlds ” (7).

Conclusion

T.S. Elliot’s proclamation that “April is the cruelest month” is not difficult to embrace when one experiences the unpredictable spring weather patterns in southwest Virginia. Yet the bard’s pessimism was thwarted on one particular April afternoon in 2005. A crowd of some 80 Wake Forest residents and their families from other areas, along with Virginia Tech faculty and students, state officials and residents of communities surrounding Kentland, were gathered to commemorate the newly placed slave cemetery monument. The air felt liquid, and a torrential downpour seemed eminent at any moment. After ministers from local African American churches offered prayers, Elder Arnold Jones, one of several ministers from Wake Forest, began a final convocation. Midway into his delivery, a hole opened in the clouds and the sun beamed through with surreal intensity. “And the Sun has just come out!” Elder Jones glee- fully injected into his prayer.

Whether act of God or natural phenomenon, no one could deny the emotional significance of the event. The meaning of the words on the memorial became clear; the descendants of those buried there had a profound tie to that land which no one else on hand could claim. As each individual from Wake Forest approached the monument to lay a flower, the mood was incredibly somber. It was clear that this was the community’s time.

In retrospect, that moment may have marked the greatest shift in authority where our collaborative projects on Kentland slave history are concerned. The nascent Wake Forest Museum is, essentially, an extension of the monument honoring the “labor, skill, blood, sweat, and tears” of enslaved ancestors. As the caretakers of the monument were the founders of the museum, stewardship of both sites is inseparable. The commemoration ceremony was in many ways a rite of passage in which the Wake Forest Community assumed full direction of historical revitalization and interpretation vis-à-vis Kentland Farm. Researchers such as ourselves came to understand our roles as brokers of social capital and occasional mediators when access to the farm has been limited by the university’s agricultural education projects. The nature of our collaboration changed, as should be the case.

Sometimes the specter of hubris overshadows archaeology, and intentionally or not, scholars refuse to relinquish authorship or control of projects that were intended to empower others. On such occasions researchers can take a cue from the annals of action anthropology, one of the unsung precursors to collaborative anthropology as we know it today. A basic tenet is that anthropologists should be committed to “promote community sustainability and capacity-building, and [to] strive to work ourselves out of a job” (8).

Notes

1. Sonya Atalay, Community-Based Archaeology: Research with, by, and for Indigenous and Local Communities (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2012).

2. Atalay, Community-Based Archaeology, 168.

3. Chip Colwell-Chanthaphonh, T.J. Ferguson, Dorothy Lippert, Randall H. McGuire, George P. Nicholas, Joe E. Watkins, and Larry J. Zimmerman, “The Premise and Promise of Indigenous Archaeology,” American Antiquity 75, no. 2 (2010): 228.

4. Luke Eric Lassiter, The Chicago Guide to Collaborative Ethnography (Berkeley, CA: Univer- sity of California Press, 2055), 16.

5. Leland Ferguson, Uncommon Ground: Archaeology and Early African America, 1650-1800 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990), 41–44; Merrick Posmanskey, “West African Reflections on American Archaeology,” in I, Too, Am America: Archaeological Studies of African-American Life, ed. Theresa Singleton (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1999): 21–37.

6. Lainie Schultz, “Collaborative Museology and the visitor,” Museum Anthropology 34, no. 1 (2011): 1.

7. Trudy Nicks, “Museums and Contact Work: Introduction,” in Museums and Source Communities, eds. Laura Peers and Alison K. Brown (New York: Routledge, 2003), 27.

8. Darby C. Stapp, “Introduction,” in Action Anthropology and Sol Tax in 2012: The Final Word?, ed. Darby C. Stapp (Richland, WA: North- west Anthropology, 2012), 2.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Blakey, Michael L. “African Burial Ground Project: Paradigm for Cooperation?” Museum International 62, nos. 1–2 (2010): 61–68.

Breunlin, Rachel, and Helen A. Regis. “Can there be a Critical Collaborative Ethnography? Creativity and Activism in the Seventh Ward.” Collaborative Anthropologies 2 (2009): 115–46.

Cook, Samuel R. “The Collaborative Power Struggle.” Collaborative Anthropologies 2 (2009): 109– 4.

Lassiter, Luke Eric, Hurley Goodall, Elizabeth Campbell, and Michelle Natasya Johnson, eds. The Other Side of Middletown: Exploring Muncie’s African-American Community. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, 2004.

Nicks, Trudy. “Museums and Contact Work: Introduction,” in Museums and Source Communities, eds. Laura Peers and Alison K. Brown, 19–27. New York: Routledge, 2003.

Stapp, Darby C. “Introduction,” in Action Anthropology and Sol Tax in 2012: The Final Word?” ed. Darby C. Stapp, 1–6. Richland, WV: Northwest Anthropology, 2012.

***

Samuel R. Cook is associate professor in the Department of Sociology at Virginia Tech, where he serves as Director of American Indian Studies and coordinator for the Anthropology major. Email: sacook2@vt.edu

Thomas Klatka is Regional Archaeologist for the Southwest Virginia office of the Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Email: tom.klatka@ dhr.virginia.gov

One Response

I purchased a picture that has a hand written note dtd 1969 stating the frame from Jerry Eaves (colored home) He was son of a slave.He worked for Grandpa Dillon. This frame is at least 70 yrs old. The frame is absolutely gorgeous & unable to find any info on design. Woman at mkt said Mr Eaves made it. I will send pic if you are interested or maybe provide info so I can continue search for info. Truly a beautiful piece. Thank you!