One hundred years ago (June 27, 1915 to be precise), Bronislaw Malinowski arrived in the Trobriand Islands of eastern Papua New Guinea to begin the fieldwork that would become legendary and shape his whole career, ultimately revolutionizing British social anthropology. He was 31 years old, a brilliant polyglot born of Polish gentry. He was highly ambitious, acutely health-conscious, inclined to hypochondria and, unfortunately for his clumsy servants and mendacious informants, prone to fits of abusive rage.

As an “enemy alien” in a corner of the British Empire at war in Europe, he was under light surveillance by the Australian authorities who ruled Papua (ex-British New Guinea). The previous year Malinowski had conducted apprentice fieldwork on Mailu Island on the south coast of mainland Papua. There he had honed his fieldwork skills and came to appreciate the methodological value of living “right among the natives” and learning their language. His ethnographic report on the Mailu, written during a brief sojourn in Australia, earned him the grudging respect of government officials and a year’s funding to continue his anthropological researches in Papua (1). Malinowski spent most of that year — from June 1915 to February 1916 — in the Trobriands.

Among the items of baggage that accompanied him to Papua were cases of tinned food, purchased and packed in London in June 1914. The technology of canning at that time allowed an astonishing range of foodstuffs to be stuffed into tin cans and hermetically sealed. When opened, the contents were not always what the labels claimed: a colonial governor in the Gilbert Islands recalled of his tinned provisions for 1916 that, “the taste of one and all…was the taste of iron filings boiled in dishwater” (2).

Malinowski’s invoices from the Army & Navy Store (“Purveyors to the Empire”) catalogue the contents of 24 packing cases shipped to Port Moresby via Sydney. The range of victuals listed is reminiscent of Rabelais’ sumptuary feasts. Bottles of Heinz tomato ketchup, lemonade crystals, jars of French mustard and Dutch beetroot, packets of dried peas and Brussels sprouts, alongside a smorgasbord of tinned delights: lobster, mackerel, oysters, sliced bacon, Irish stew, Swiss cheese, Peters milk chocolate, Heinz baked beans, Bournville cocoa, Spanish olives, petits pois and cod roe. Other packing cases contained tins of Nestles milk, six different jams, kippered herrings, various dried fruits, a jar of extract of beef, a bottle of Camp coffee, and a variety of biscuits, rusks and crackers. There were other cases of toothsome tinned foods: essence of chicken, jugged hare, roast turkey and half-hams. Yet another case contained two bottles of French brandy, three bottles of ink, four 2 lbs tins of Epsom Salts, 6 lbs of boric acid, bottles of tincture of iodine, and assorted packs of bandages, lint and cotton wool — and one toothbrush (3).

***

The question posed by the title of this essay was put to me by Dr. Linus digim’Rina, a professional anthropologist trained in the Malinowskian tradition some 20 years ago under my supervision at the Australian National University; more pertinently he is a self-described “native” of the Trobriands (4). Having carefully perused Malinowski’s two notorious field diaries, as published by his widow in 1967 under the title A Diary in the Strict Sense of the Term, Linus was puzzled by the paucity of references to the ethnographer’s dietary habits. His curiosity led him to ask the simple question, one of great relevance to any Trobriander: “What did Malinowski eat while living in the village?”

As will be evident to the most casual reader of the Diary, Malinowski’s appetite for food was insignificant compared to his preoccupation with sex. Before considering his dietary concerns, therefore, it will be as well to get the sex out of the way as it is such a prominent theme of his diaries. He wrote obsessively about his daily tussle with sexual distractions and about his nightly struggle “under the mosquito net” to banish lascivious fantasies. Observing “a finely built [Trobriand] girl” walking ahead of him one day, Malinowski “watched the muscles of her back, her figure, her legs, and the beauty of the body so hidden to us whites.” He added: “I was sorry I was not a savage and could not possess this pretty girl” (5). Only a few weeks earlier, with his fiancée Elsie Masson in mind, he had written: “I shuddered at the thought of betraying her” (6).

There has been a great deal of speculation about whether he did, or did not, have sex with the shameless young “sirens” with “whorish faces” who flit through the pages of his Trobriand diary. He confesses at times to “patting” or “pawing” them (“I couldn’t keep my paws off the girls,” he laments) before roundly castigating himself for betraying the image of the faithful fiancée in Melbourne awaiting his return. “Pawing” in private is not a scandalous offence in the Trobriand view, and had he been challenged he could well have used a variant of the Clinton Defence: “I did not have sex with that savage!” (7).

Linus digim’Rina recorded the oral testimony of an old man of Oburaku village who told him that Malinowski “gave tobacco to women as payment for sexual favours. Because he was new, the women were very fond of him” (8). The veracity of this legend is open to serious doubt, however. His fear of caste-based sexual pollution and his dedication to “spiritual purity” for Elsie’s sake tell convincingly against it. So too does the brutal honesty and scorching self-examination of a private diary not intended for publication; had he succumbed even once, his diary would have been awash with guilty remorse (9). Linus made the sensible observation that had Malinowski rid himself of racial prejudice and “availed himself of the sexual temptations on offer…he might have appreciated the life around him as a native does” (10).

A former mistress, Annie Brunton, nailed the issue in a letter to Malinowski after he had teasingly sent her provocative photographs of New Guinea belles. “Those native girls seem so very well set up, good looking girls,” she commented. “Are they free from disease? I think it is quite wonderful the ‘dream of your youth’ has not yet been realized with regard to them.” She knew him well enough to guess that if he were to realize his dream of consorting with “dusky” maidens “there would be an after feeling of disgust” (11). Precisely. A residual Catholic conscience — fortified by a fear of racial pollution and a horror of venereal disease — helped Malinowski keep nubile Trobriand sirens at arm’s length.

***

In his first fieldwork diary, in which he records — on an almost daily basis — his activities between September 1914 and February 1915, there are scarcely any references to what he eats. A rare entry mentions that his lunch in Samarai, taken while walking around the tiny island, consisted of “three bars of chocolate” and the next day a lunch of “chocolate and biscuits.” He refers more often to what he drinks, such as coconut milk, lemonade, soda water and ginger ale. He preferred tea and cocoa to ersatz “Camp” coffee. Tea was his most regular drink, morning and night, and he sometimes over-in-dulged: “Slept well — I did not drink tea, and this was a good thing” (12).

When socializing in the colonial townships of Port Moresby or Samarai he consumed alcoholic drinks: beer, sherry, claret and shandy (beer diluted with lemonade). In hot and humid Port Moresby it was “pure bliss” to drink “two enormous glasses of icy beer.” On Woodlark Island, he spent a night carousing with a motley collection of itinerant whites: “I drank beer and got tight.” Twice he records thirsting for a glass of shandy (the translator mistook his rendering of the word for “brandy”); though two bottles of French brandy were invoiced by his London supplier and he twice mentions drinking brandy: “At home [i.e. a hut in Mailu] I drank a brandy and soda, after which a headache, bromide, massage” (13). The only other reference to imbibing alcohol while in the village suggests that he used it medicinally to help him recover from an exertion. He appears to have had quite a low tolerance for alcohol and was prone to hangovers. When sailing back to Australia in March 1915 he drank three glasses of beer one evening; the next day he reacted extravagantly with a “hangover, or fever — sluggishness, anaemia of the brain, no energy” (14).

***

Malinowski kept no diary during his second period of fieldwork, which he spent entirely in the Trobriands. After a lengthy spell of 20 months in Australia, he returned to the Trobriands in late 1917. “A Diary in the Strict Sense of the Term” is the title he gave to the journal he kept between October 1917 and July 1918. In its recording of daily minutiae it is rather more informative concerning his eating habits.

In Oburaku, the lagoon village where he lived for three months, he regularly ate fresh fish. “What I eat at present,” he helpfully noted on 19 December 1917: “morning cocoa; lunch relatively varied, and almost always fresh food. Supper very light, banana compote, momyapu [papaya or pawpaw]; once I ate a lot of fish and felt no ill effects” (15). On another occasion he “gorged” himself with fish and spent an uncomfortable night. He also “gorged” himself with pork loin at a white trader’s compound. Some of the “relatively varied” lunches he recorded in his Trobriand diary were “eggs and cocoa,” “crab and cucumber” and “fried taro” with fish. He called stewed bananas “a wonderful invention.” The adjective he most often used to describe his lunch was “frugal.”

Malinowski did not cook for himself, but nor did Trobriand men, except when in their gardens or on an overseas kula expedition (16). Cooking was done on an open fire, though Malinowski mentions having a “camp oven.” In Samarai, waiting for a boat to take him to the Trobriands, he recruited Ginger, a red-haired young man from nearby Sariba Island, to serve as his “butler, cook, and personal attendant.” Ginger was less familiar with the domestic routines of white men than he had claimed, so Malinowski (“in the role of Haus-frau” as he wrote to Elsie) had to instruct him “how to wash the crockery, how to cook, make the bed etc” (17). One of his first lessons, accompanied by “yelling and swearing,” was how to fry eggs in lard. Another of Ginger’s tasks was to fetch the weekly loaf of bread and jug of milk from Billy Hancock, a Cockney pearl-trader based on the northern shore of the lagoon. For eight months the hapless Ginger bore the brunt of his master’s colourful invective and outbursts of temper. After an “unpleasant clash” Malinowski even admitted that he “punched him in the jaw once or twice” (18).

On 27 January 1918, Malinowski “woke up sick” and for three or four days suffered “splitting” headaches and a high fever (probably malarial). He could not eat and had “no desire to live.” He dosed himself with quinine and aspirin and wondered idly whether he was about to die (“I am indifferent,” he wrote). On the third day he “took an enema” which relieved him: effervescent salts, he noted, “turns out to be my salvation.” A week later the violent shivering and high temperatures returned and he suffered another bout of sickness, moral dejection, and loss of appetite. He now suspected black-water fever, and even entertained a “hypothesis of septicaemia: had eaten stale soup… with Maggi and mouldy rice” (19). The next day he took no food or drink.

On 11 February he felt better and “ate 1 toast for lunch.” With the “fetters of sickness” easing, he had felt “horribly hungry: visions of vol-au-vents de volaille. French chop-houses in Soho, etc. attract me more than the loftiest spiritual joys” (20). This is the only occasion in the diary when he notes that he is hungry. He had been spending the days lying in his tent quietly reading Charlotte Bronte’s novel Villette, which had strongly influenced his mood. “Eating, too, plays a great role in my present outlook,” he wrote, possibly an- other allusion to hunger pangs.

Oburaku men went fishing a few days later and Malinowski “bought a lot of fish” which he “boiled” and “drank fish soup avidly.” On 13 February he wrote to Elsie about his relapse and how he had starved himself for three days. In that letter he told her that the three available fresh foods he liked best were “bananas, eggs and pawpaw.” Taro was also “a splendid thing & I thank God for having created it, but even the best things get monotonous” (21).

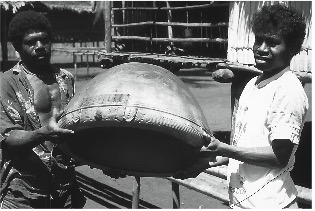

He described and photographed the cooking of mona, a sumptuous feast food of taro ‘dumplings’ simmered in oily, heartburn-inducing coconut cream. Women mash the cooked taro and shape them into dumplings, while men scrape coconuts and cook the mona in huge pots traded from the Amphlett Islands (22). Malinowski relished this local culinary creation, and he described its ceremonial preparation for Elsie:

It is a big affair: the big clay pots put up in the village, lots of scraping, beating, coconut cream prepared, big wooden ladels [sic] to mix the mess… The whole thing somewhat in the style of the Polish X-mas Eve meal: two days of preparing, then 10 minutes of cooking, then the stuff is gulped down in a few minutes and the whole fun is over. The main point of it is in the preparation of course. (23)

On that day in Oburaku he lunched on eggs and cocoa.

Linus specifically wondered how many “local foods” Malinowski ate. The diary records the following fruits and vegetables: banana (the sweet variety, not the cooking banana or ‘plantain’), sweet potato, pumpkin, cucumber, papaya (or pawpaw), beans, pineapple — all of which were introduced only after European contact in the late 19th century.

Of the indigenous foods available he does not mention eating any of the following: sago, breadfruit, mango, canarium nut, Tahitian chestnut, aibika greens, pandanus fruit or sugar cane. (It is hard to believe that he didn’t chew on sugar cane when visiting the gardens, as villagers usually do.) He mentions chewing betel (areca) nut only once, but there is a photograph showing him with Billy Hancock preparing — or pretend- ing — to chew (24). The most exotic vegetable item he enjoyed was “coconut cabbage” or “coconut salad.” This was made from the crisp inner “heart” of the crown of the coconut palm, which can only be harvested by cutting down the mature tree. It was a rare luxury, therefore, and Malinowski refers to having eaten it only twice, on successive days, which suggests that a single coconut palm had been felled in Oburaku for some other purpose.

Just once does he record eating yams (the Trobriand staple), albeit cautiously. At Wawela on the open “sea” side of Kiriwina, there was a “picnic mood” on the beach with his local companions, eating a lunch of roasted sardines and yams. “I got up my courage and ate towamoto (very tasty),” Malinowski wrote (25). Towamata [sic], according to Linus, is mashed yam or other vegetables boiled and creamed with shredded coconut.

The eggs Malinowski ate were those of the domestic chicken — a fairly late introduction to the islands. He does not mention eating the larger eggs of the bush-turkey (megapode) which villagers most certainly did. Nor does he mention other exotic local cuisine such as turtle, shark, crocodile, flying fox, possum, or edible seaweed. He refers just once to eating oysters (paku). There was little game to be caught on the heavily populated and thinly forested Trobriand Islands, but though wild pigs and a variety of birds were trapped by villagers, Malinowski does not mention eating them. He does note the “very tasty” pork of the European pig (bulukwa miki) introduced to Kiriwina by the trader Mick George.

In short, Malinowski’s consumption of local foods fell within a very limited range of those available. From a Trobriand perspective, Linus’s criticism is valid: “An ethnographer who claimed to have immersed himself among the natives did not even have a simple appreciation of much of the local food” (26).

***

On New Year’s evening Malinowski rowed to Billy Hancock’s place — a two-hour pull in Mick George’s borrowed dinghy. The next day, after taking photographs of village activities with Billy, he “ate too much” at lunch but worked it off by rowing back to Oburaku, where he partook of “tea with a drop of brandy.” And under the mosquito net that night he indulged in introspection:

I realize once again how materialistic my sense reactions are: my desire for a bottle of ginger beer is acutely tempting; the thorough eagerness with which I fetch a bottle of brandy and am waiting for the bottles from Samarai; and finally I succumb to the temptation of smoking again. There is nothing really bad in all this. Sensual enjoyment of the world is merely a lower form of artistic enjoyment. What is important is to be quite clear in one’s mind about it, and not to let it interfere with essential things. On the other hand, I am perfectly capable of an all but ascetic life. The main thing is that it should not matter. (27)

Over-eating certainly did not agree with him. Once when visiting one of the resident white traders, he “gorged” himself at an “abundant supper” of “pork, potatoes and custard,” and the next day he was “edgy, tense: in addition, intense stomach-ache, overeating — I couldn’t eat a thing” (28).

Throughout his life Malinowski fasted frequently with an almost fanatical belief in its efficacy. In his Trobriand diary he mentions dieting or fasting at least a dozen times. His dieting regime was inadvertently aided in May 1918 by a physical impediment to eating: he broke his upper dental plate. Although as “toothless” as he had been in Melbourne the previous year, he told Elsie with philosophical equanimity that he could “eat almost everything and I am not at all depressed about it” (29) But he was “seedy” again a few days later, telling Elsie that he had “fasted the whole day yesterday and eaten not much today and I am feeling much better, but I am not going to intone a Te Deum yet….”(30). Later in his fieldwork, following another spell of sickness, he told Elsie about his “medicinal discovery” which has “the virtue of cheapness” besides providing a cure. “I eat nothing for two or three days and this puts me quite right” (31). This was his “hunger cure.”

It is curious how infrequently Malinowski mentions eating any of the canned foodstuffs that he shipped to Papua. Just twice: kippers and oysters. For lunch in Oburaku one day he “experimented with tinned oysters,” but the following day he felt “poorly” and wondered “could it be that tinned food again affected me?” (32) (The “again” is ominous.) So what happened to all the other canned delicacies? Did he give his tinned cod roe to the fishermen of Oburaku? Did he share his tinned bacon and jugged hare with his pearl trader friends? Will a buried horde of rusty tin cans be unearthed one day in Kiriwina by a puzzled archaeologist?

It seems more likely that most of those cases of tinned foods never reached the Trobriands at all. In an early letter to Elsie, Malinowski mentions that his first task on arriving in Port Moresby was to investigate the state of “the greater part” of the provisions he had shipped from London. In September 1914 he had stored them (“as I was over-stocked”) in a trader’s basement where they remained for the next three years. “They look very dusty and musty at present,” he added, “and I’ll have to open a number of them, so as to see whether they are still edible” (33).

Given this contingency, and considering his penchant for dieting and his tolerance of hunger, this essay has had to be as much about what Malinowski did not eat in Papua.

Notes

1. Michael W. Young, Introduction to Malinowski among the Magi: “The Natives of Mailu” (London: Routledge, 1988).

2. Arthur Grimble, A Pattern of Islands. (Lon- don: John Murray, 1952), 85.

3. Michael W. Young, Malinowski: Odyssey of an Anthropologist, 1884-1920. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004), 265–6.

4. Linus digim’Rina, “From the Angle of ‘a Native’ and a Fieldworker,” Review Forum for Malinowski, Odyssey of an Anthropologist, in The Journal of Pacific History, 40, no. 2 (2005): 246–8. Dr digim’Rina currently heads the department of anthropology at the University of Papua New Guinea.

5. Bronislaw Malinowski, A Diary in the Strict Sense of the Term, tr. Norbert Guterman (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1967), 255.

6. Diary, 224. In what follows only longer quotations from the Diary will be sourced by page numbers.

7. Like his contemporaries, Malinowski made liberal use of the term ‘savage’. Cf. Crime and Custom in Savage Society (1926), Sex and Repression in Savage Society (1927), and The Sexual Life of Savages (1929).

8. Young, Odyssey of an Anthropologist, 529.

9. Censored passages in the posthumously published Diary were restored for me by Ms Basia Plebanek, a Polish translator who consulted the original diaries. None of his widow’s redactions and elisions suggest that Malinowski did anything more than luridly fantasize.

10. Digim’Rina, op.cit. 247.

11. Annie Brunton to Malinowski, 15 August 1915, cited in Young, Odyssey of an Anthropologist, 405.

12. Diary, 65.

13. Diary, 66.

14. Diary, 97.

15. Diary, 156.

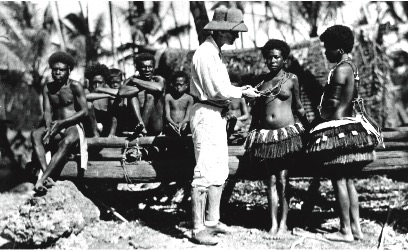

16. See plates 182 and 183 in Michael W.Young. Malinowski’s Kiriwina: Fieldwork Photography 1915–18 (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1998), 260–61.

17. Malinowski to Elsie Masson, 13 January 1918. The Story of a Marriage: the Letters of Bronislaw Malinowski and Elsie Masson, volume 1: 1916–20, edited by Helena Wayne (London: Routledge, 1995), 78.

18. Diary, 250.

19. Diary, 200.

20. Diary, 201.

21. Malinowski to Elsie Masson, 13 February 1918. Malinowski Papers, London School of Economics.

22. See plates 99, 100, 101, 102, and 149 in Young, Malinowski’s Kiriwina, op,cit., 165–68, 220.

23. Malinowski to Elsie Masson, 14 December 1917. Story of a Marriage, op.cit.,79.

24. See plate 14 in Young, Malinowski’s Kiriwina, op,cit., 55.

25. Diary, 220.

26. Digim’Rina, op. cit., 247.

27. Diary, 171.

28. Diary, 214–15.

29. Malinowski to Elsie Masson, 14May1918. Story of a Marriage, op.cit., 148.

30. Malinowski to Elsie Masson, 19May1918. Story of a Marriage, op.cit., 149.

31. Malinowski to Elsie Masson, 25 August 1918. Malinowski Papers, London School of Economics.

32. Diary, 206, 208.

33. Malinowski to Elsie Masson, 2 November 1917. Story of a Marriage, op.cit., 34.

Michael W. Young is a visiting fellow in the College of Asia and the Pacific at the Australian National University, Canberra. Born in Manchester, England, he studied anthropology at University College London and the ANU and has conducted fieldwork in the Massim area of Papua New Guinea and in Vanuatu. His ethnographic works include Fighting with Food (Cambridge 1971) and Magicians of Manumanua (California 1983). He has authored several books on the pioneering work of Bronislaw Malinowski and is currently completing the second volume of a biography.

One Response

I first heard of Malinowski in 1968 when enrolled in Anth 101 at university in Wellington New Zealand Aotearoa. After all that time i have finally got to read his ‘Argonauts of the Western Pacific’ (now 2025). i really appreciate this article by Michael Young since it provides a complementary picture of the remarkably gifted man as a man.

You do have to wonder how he lived on a day to day basis, and why it should be anthropologists went to do fieldwork without companions of their own – but Malinowski said that is what brings you into better closer contact with local peoples.