Politics makes visible that which had no reason to be seen.

—Jacques Rancière

Whether ultimately approved or not, the Keystone XL Pipeline offers a telling window into the contemporary politics of fossil fuels in North America. Although oil pipelines have been around for a century, they have long been neglected in scholarship and public debate. Today, that is beginning to change. Whether as a strategic vehicle for energy independence or as an urgent front-line in the fight against climate change, oil pipelines are increasingly understood not as inert things but as consequential projects in our troubled present. During the Fall 2014 semester I taught a seminar at Bennington College that used the promises and protests surrounding the Keystone XL as a prompt to reflect more broadly on questions of vital infrastructure and social change today.

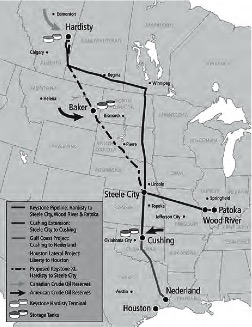

In preparation for the seminar, I rented a car this past summer and drove the presumed path of the Keystone XL through Nebraska, South Dakota and Montana. Owned by the TransCanada Corporation, the Keystone Pipeline System consists of four phases, the first three of which are already built and in operation. Phase One repurposed existing natural gas pipelines and built new pipelines to connect the Alberta oil fields to Winnipeg, some 700 miles to the east, before heading due south to a pipeline junction in Steele City, Nebraska. Phases Two and Three installed a new 36-inch-diameter steel pipeline that linked the refineries of Houston, Texas, to the Steele City junction. The controversial Keystone XL seeks to extend this new pipeline from Steele City directly to oil terminals in Alberta, forming a sort of hypotenuse on the existing Keystone system. As designed, the Keystone XL is really just a shortcut.

It is worth noting that the Keystone XL is far from the first or even the only conduit bringing tar sands oil into the United States. Trains carrying crude from the tar sands have become commonplace in many parts of the country, and a handful of major pipelines now carry bitumen diluted with chemical solvents, or “dilbit,” from Alberta to US refineries. In many cases, pipeline companies retrofitted or simply reversed the flow of existing pipelines to avoid the public scrutiny of a new project. The Keystone XL is unique in that, as a new border-crossing pipeline, it requires the State Department to review its impact and attest to the project being in the national interest.

The thousand-mile route of the Keystone XL cuts across the northern Great Plains, from windswept cattle ranches in Montana to the lush farms of Nebraska. After crossing the Canadian border, the Keystone XL heads down to Baker, Montana, where its Canadian cargo will be joined by the current glut of domestic crude coming out of the Bakken Formation in North Dakota and Montana. Mindful of potential points of resistance, the pipeline then squiggles its way eastwards through Montana and South Dakota in studious avoidance of Native American reservations. In Nebraska, the first draft of the Keystone XL drew a rather brash line across the Sand Hills and Ogallala Aquifer. This route elicited such indignation from local farmers that TransCanada quickly adjusted it, now swinging the pipeline out along the edge of the aquifer. These changes to the route were mired in the Nebraska courts for several years, as the law is unclear on who actually has authority to change the plan. The Nebraska Supreme Court approved the adjusted route on January 9, 2015.

Although Keystone XL steers clear of major cities, it does pass by about 15 small towns. In contrast to what is so often reported from afar, in towns including McCool Junction, Nebraska (pop. 413), Midland, South Dakota (pop. 127), and Circle, Montana (pop. 617), I met folks who are neither adamantly for or against the pipeline. Beyond the green-clad pipes being stockpiled in an empty field just outside Buffalo, South Dakota (pop. 380), the Keystone XL had little visible presence in these towns. There were no yard signs expressing an opinion. There were no rosy company billboards, either, and the products of the sizable social in- vestments TransCanada is making locally, such as digital scoreboards for high schools and upgrades for fire departments (now equipped to fight chemical fires), did not exactly advertise their funding source. Trans-Canada’s television advertisements for the Keystone (entitled “Straight Talk”), however, draped the company in the folksy authenticity of these small towns. When I asked directly, many residents around the oil fields of Montana voiced their support for the project, while many residents in the Sand Hills of Nebraska voiced discontent. But overall, most people I talked with along the route were ambivalent about Keystone XL, keen to have some decent local jobs but wary of the gloss of big corporations, especially foreign ones.

Walking down neighborhood streets strewn with rusty equipment and empty lots, it was not hard to imagine where this hesitation might originate. So many of these towns originally sprang up alongside the movements of people and goods, trying to capitalize on whatever happened to be passing by. They have stitched their history together with the debris of military pacification campaigns, immigrant settler trails, transcontinental railways and most recently, the interstate highway system. They are frontier towns, with all the colonial overtones and social histories of catch as catch can such description implies. They have seen boom and bust before, both in the feverish future the adjacent traffic promises and in the ruins so often left behind. Today, huge granaries fall into disuse along railways now crowded with coal trains that don’t make any local stops. What commerce remains has drifted from boarded-up main streets to single gas stations on outskirts nearer the highway. In these ways and others, the towns along the Keystone XL route already bear the imprint of shifting material histories of transportation. They are not so much out-of-the-way— indeed, what success they have had is owed to being very much in the way—as they are ever more meticulously passed by.

If the Keystone XL is approved, a near astronomic amount of wealth will soon flow by these towns. And yet to an almost unrivalled degree, the wealth pouring through the 36-inch diameter steel pipe will accrue in concentration elsewhere (the risks, of course, will be widely distributed). The nation’s vital economic networks don’t seem to “leak” nearly as much as they used to, at least not of the stuff that might enable peripheral communities to prosper.

Most of the local relations of obligation engendered by this pipeline will be resolved in a single transaction. About 2,000 property owners will receive checks as compensation for granting the Keystone XL a permanent easement. Most will do so under the express threat of a state-authorized and Supreme Court–sanctioned form of “eminent domain” that holds up corporate interest as a legitimate measure of the public good (1). Municipalities might see an uptick in tax revenues to fund long-needed school improvements and perhaps less needed property tax breaks for residents. At least that’s what communities have been promised, except those in Kansas. There a legislative arms race to see who could appear more pro-pipeline—a one-upmanship that appears to have taken even TransCanada by surprise—exempted all new oil pipelines from paying taxes at about the same time the state’s budget was slipping into serious financial turmoil. While local communities might see a flurry of workers who need housing, food and ame- nities during the construction boom, once built, the pipeline will be operated out of an office in Calgary. Keystone will require, at most, a handful of permanent workers in the United States. It is not until after the pipeline is buried and out of sight that the real wealth will start to flow, to the tune of about 800,000 barrels of crude oil a day. And of that most lucrative flow, local communities will see very little if anything at all.

***

The Keystone XL is an apt example of what political theorist Timothy Mitchell calls “Carbon Democracy” (2). According to Mitchell, fossil fuels have played crucial if overlooked roles in shaping the practice of democracy today, in both its social aspirations and its technical limits. At the dawn of the 20th century, coal was at once essential to industry and quite labor-intensive in its extraction and distribution. The dawning awareness of this reality joined disparate workers and empowered them to seize control of key energy chokepoints in order to make broad social demands, an insurgence that compelled companies and governments to expand their civic responsibilities. The extraction and distribution of crude oil in the post–World War II period moved in a decidedly different direction. Through imperial interventions, unmanned infrastructure and oceanic shipping, the networks of crude oil worked to override earlier points of labored friction. In their design and operation, petro-systems have become quite adept at dodging and disabling robust forms of public accountability. For Mitchell, oil pipelines are the premier example of this ongoing occlusion of workers and citizens. Driving through the small towns along the route of the Keystone XL this past summer, I could not help but reflect on how unremarkable this foreclosure of political possibility has become.

Two months later, I attended the People’s Climate March in New York City. On the streets of that spirited and truly immense gathering, the Keystone XL had not foreclosed political possibilities but caused them to proliferate. Not only was an anti-Keystone XL message proclaimed in posters and rallying calls, but other pipelines including the Alberta Clipper in Wisconsin, the Exxon Pegasus in Arkansas and even the proposed Cove Point liquid natural gas terminal in Maryland were the focus of notable scorn. One group of marchers wore baseball jerseys identifying themselves as “Pipeline Fighters.” Another group, in a lively performance, dressed as a black hydrocarbon octopus whose sprawling tentacles became pipelines that chased wildlife down Sixth Avenue. While the People’s Climate March lined up all variety of suspects for cathartic castigation, I was still taken aback by how ubiquitous pipelines have become in climate activism. A decade ago, I don’t think any environmental activists in the United States could have predicted that pipelines would become such a rallying point.

I wondered if climate activism could be cultivating a new kind of social change, and if the growing presence of pipelines might have something to do with this shift. By and large, the environmental movement in the United States has been proscriptive, not preventative. Environmentalism gained moral and regulatory force in the outraged response to specific industrial disasters. Whether it was the suffocating smog of Donora, the flammable Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, the declaration that Lake Erie was dead, the smothered California coast during the Santa Barbara oil spill or the domestic discovery of toxic waste in Love Canal, again and again it was spectacular events that catalyzed nascent environmental concerns and instigated change in policy to prevent their reoccurrence. In contrast, climate change demands public action not in reaction to an acute disaster but in anticipation of the diffuse disaster to come: a slow unraveling of the planet’s climate. Although residents of the Maldives, Philippines and coastal New Jersey might disagree, for many people climate change does not yet have the density of a deeply felt event. As the novelist Zadie Smith points out in her essay, “Elegy for a Country’s Seasons,” climate change is a disaster for which there is a “scientific and ideological language” but “hardly any intimate words” (3). It is hard to imagine how one would mobilize around the turgid prose of, say, the Fifth Assessment Report of the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. How do you protest the predicted event? Where do you even begin?

A few years ago, a starting point in the fight against climate change suddenly emerged: the material infrastructure of fossil fuels. Although neatly sidestepping the more consequential question of what to do with those distinctly American lifestyles built on the presumption of hydrocarbon abundance, infrastructure nonetheless offered a practical place to begin. In 2011, the pent-up frustration of those incensed by the lack of action on climate change rather potently aligned with the Keystone XL permitting process. It was NASA Scientist James Hansen who first pointed out this convergence. In “Silence is Deadly,” an open letter posted online, Hansen noted that the window for public comment on the Keystone XL was about to close. He encouraged all concerned citizens to spread the word and log their discontent. “If this project gains approval, it will become exceedingly difficult to control the tar sands monster,” he wrote. Extracting and burning all the hydrocarbons in the tar sands, Hansen argued, would push global warming well past the point of no return. If the Keystone XL were built, Hansen concluded, “it is essentially game over” (4).

Bill McKibben, among many others, took note of Hansen’s letter and got to work. McKibben and the organization he helped found, 350.org, have labored tirelessly to publicize the otherwise mundane process of permitting a new border-crossing pipeline in the United States. When that regulatory process didn’t seem particularly newsworthy, the organization found creative ways of making it so, whether by writing vehement op-eds, overwhelming the public input process or getting arrested at the White House on prime-time television. Other national environmental organizations have followed suit, and today the Keystone XL is regularly described as the “lynchpin” to the tar sands or even as the “fuse” that will ignite climate change.

In Nebraska, a parallel resistance to the Keystone XL has taken shape, albeit one less concerned with how fossil fuels contribute to climate change than with how the Keystone XL might undermine regional agriculture. The organization Bold Nebraska has become particularly skilled at reframing the Keystone XL as an intrusion on property rights and thus a litmus test for state politicians by posing the question: Do you support the pipeline or local farmers? Another organization, the Cowboy and Indian Alliance, has capitalized on the iconic convergence of interests that opposition to the Keystone brought about. As Tony Horowitz reports in his book Boom, at one Cowboy and Indian Alliance meeting a rancher lashed out at TransCanada’s strategy of eminent domain, “They’re taking our land!” Realizing the disquieted history of his statement, the rancher added, “I guess that’s what happened to you. Now it’s happening to us” (5).

Alongside this renewed activism, many online news platforms including ProPublica and Inside Climate News have directed their talented investigative reporting teams towards the Keystone XL. National news outlets often followed their lead. This burst of attention has revealed many embarrassing lapses in planning and regulatory documents that never anticipated such scrutiny. In an era of shrinking journalistic resources, this in-depth coverage of proposed oil pipelines is quite remarkable. My local NPR station now regularly covers the Addison Natural Gas Project in Vermont, whose proposed pipeline has inspired a new kind of civil disobedience: the knit-in. On December 9, 2015, the Wall Street Journal published an article entitled “Protests slow pipeline projects across U.S., Canada.” Pushed onto the national stage, pipelines are a common fixture in the unfolding present.

While popular accounts of this sudden interest in energy infrastructure often hang the story on the Keystone XL, there might actually be a much bigger change going on here. Over the past decade, and in ways often unnoticed in the United States, oil pipelines around the world have become unexpected battlegrounds in wider environmental disputes. The OCP pipeline in Ecuador has been a major flashpoint for campaigns to save the rainforest and protect the indigenous peoples living there. The BTC pipeline linking the crude reserves of the Caspian Sea to Europe in a way that bypasses Russia became a rallying point for local environmental groups such as Green Alternative in Georgia and international groups including Platform UK in London, whose members published an incisive travelogue of the pipeline in 2012 (6). Although its history is linked to the Keystone XL, the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline in British Columbia has helped to reactivate distinct genealogies of indigenous discontent in Canada, working to catalyze the Idle No More movement. Perhaps the controversy over the Keystone XL is merely the US version of this wider realization of petro-networks.

Marching down Sixth Avenue during the People’s Climate March, it was striking how prominent oil pipelines have become, although in particular ways. In so much of the spirited antipathy directed at the Keystone XL on that September day, the physical pipeline and the communities it touches seemed to matter less than the planetary crisis the Keystone XL has been asked to represent. While Nebraska offers an interesting exception, global warming trumps local context in orienting outrage around the Keystone XL. For many activists I spoke with at the protest, the Keystone XL was not so much a 1,179- mile shortcut on an existing pipeline system as it was the frontline in the urgent battle against climate change. Several people could not even identify the states through which the pipeline would pass.

It is notable that the express goal in this rising climate activism around pipelines is not to hijack the physical infrastructure in order to make outsized social demands, like the coal strikers of old. The aim is not to occupy key energy chokepoints, but to trip up the tidy image of fossil fuel infrastructure as “safe, silent, and unseen,” to borrow a popular industry description of pipelines. In the People’s Climate March, protesters creatively entangled oil pipelines in narrow conduits of profit, broad patterns of destruction and the looming possibility of a foreclosed future. The emerging mantra might be: Don’t seize control, seize the implications. In all of this, oil pipelines are being confronted more as ecologies of harm than as buried metal tubes. While the relations of consequence being pinned on petro-infrastructure seem to exceed the communities immediately adjacent to them—as evidenced in both the ambivalence of many towns along the Keystone route and the absence of those communities in climate activism—such relations have nonetheless given these material networks a new scale of transparency. Oil pipelines have become, well, visible. And in that rising visibility, petro-networks are being opened up to new forms of accountability and refusal.

Notes

Photos by David Bond

An earlier, abridged version of this paper appeared in Bennington Magazine, a publication of Bennington College.

(1) In one way or another, the state govern- ments along the route all authorized TransCanada to use eminent domain to seize private property for the pipeline’s construction. Kelo vs. New Lon- don (2005), the controversial Supreme Court case that backs such seizure, ruled local governments could confiscate homes and small businesses to make room for corporate investments. One inter- esting addendum to this case: five years after its Supreme Court victory, the corporation (Pfizer) who promised to develop New London closed down its office complex and moved the heralded 1,400 jobs elsewhere.

(2) Timothy Mitchell, Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil (London: Verso, 2011).

(3) Zadie Smith, “Elegy for a Country’s Sea- sons,” New York Review of Books, April 3, 2014, p. 1.

(4) James Hansen, “Silence Is Deadly,” June 3, 2011 (accessed January 15, 2015) [http://www. columbia.edu/~jeh1/mailings/2011/20110603_SilenceIsDeadly.pdf]

(5) Tony Horowitz, Boom: Oil, Money, Cowboys, Strippers, and the Energy Rush that Could Change America Forever (Amazon Kindle Single, 2014), Kindle Location 1558-9.

(6) James Marriott and Mika Minio-Paluello, The Oil Road: Journeys from the Caspian Sea to the City of London (London: Verso, 2012).

David Bond teaches anthropology at Bennington College. From the BP oil spill to the tar sands of Alberta, his research describes how the afterlives of fossil fuels are opening up new political fields for rule and resistance around the conditions of life.